Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

- After the voluminous first part, one could ask if there was enough new material to justify a second volume

- Therefore, his determination to put on record this chaotic, controversial and the bleakest chapter of our contemporary history is both understandable and commendable

- This writer believed, and still does, that if the JVP had succeeded, its leaders would have chosen the Maoist-oriented Pol Pot path of destruction

- The math is simple. The death toll from both JVP rebellions and the LTTE-led Eelam Wars is estimated to be over close to 200,000

- Most of those killed were young. Almost all had studied up to GCE O level or A Levels, some were graduates

- The author claims that about 2,000 female JVP members were ‘disappeared or executed’. Unlike their male counterparts, only a handful had the luck to survive and undergo rehabilitation

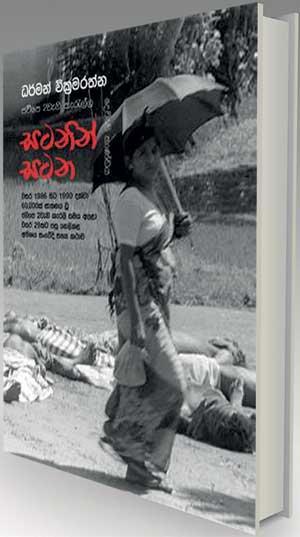

‘Satanin Satana,’ the second part of Dharman Wickremaratne’s history of the JVP’s second rebellion has followed the first with commendable speed. The first volume had so much detail that one would have believed it to be conclusive. But, as the second volume shows, there were many more related stories waiting to be unearthed.

Much of it is blood and gore. After the voluminous first part, one could ask if there was enough new material to justify a second volume. A glance through this 1,020 page book shows that there was. While working within the framework of the 2nd rebellion’s inception and bloody finale (with a certain amount of repetition being inevitable), the second volume contains new ground covered previously only sketchily by the media, such as the significant roles played by JVP’s child and female cadres, the post-Wijeweera power struggle for leadership, and how the Sinhalese diaspora in the West continued to support what had become a lost cause, though with nothing like the vehemence which fuelled the Tamil diaspora vis-a-vis the LTTE.

As noted in my review of the first volume, author Dharman Wickremaratne, as a young reporter for the Divaina newspaper, was witness to many of the key events of the rebellion and its aftermath. A skilled negotiator with considerable personal charm, he was able to maintain contact with various conflicting groups and factions, some official and some shadowy, and work under daunting conditions. Under pressure from the government, the Upali Newspapers (Pvt) Ltd. was forced to ‘sack’ him for two years though it kept him on the payroll.

He faced death threats. Therefore, his determination to put on record this chaotic, controversial and the bleakest chapter of our contemporary history is both understandable and commendable.

"This situation changed during the latter stages of the Eelam War, but the result now is worse – an oversized military (relative to the country’s size and wealth), leaving vital areas such as education, health, public transport and infrastructure (forget the highways and look at the unguarded rail crossings) underfunded"

The book is a personal initiative, the result of an asto nishing personal commitment involving considerable legwork and physical labour. He travelled all over the island for several years, using public transport, interviewing people from both sides, survivors and families of those killed. Many were reluctant to talk. The author needed all his personal charisma and powers of persuasion to get the stories, photographs and documents needed to piece together this wretched history – wretched it is, as it becomes clear that increasing arrogance on both sides and an almost psychopathic belief in the power of violence resulted in thousands more unnecessary deaths following the capture and execution of JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera in November 1989. The JVP and its military arm the DJV, in an insane attempt to avenge Wijeweera’s death and to achieve final victory, continued its murder and violence while the state’s security organs and other paramilitaries reacted ferociously, convinced that more and more killing would finally crush the rebellion. It did.

In restrospect, what matters is not who was right. What matters is that the wrong conclusion drawn from it – that trying to topple the government by armed rebellion is futile given the island’s geopolitical context, whereas it was more important to address the deep rooted grievances which make people rebel. Socio-economic inequality tops this list and that has increased exponentially since the days of the 2nd rebellion.

A vital part of this lesson is that there will be no hope of justice for those slain. The operating logic and wisdom is that the JVP started the violence, hence they deserved what they got. This is Hammurabi’s law, an eye for an eye, multiplied exponentially. Anti-government rebellions are not unique to us. Both Africa and Latin America have experienced them considerably. But a number of Latin American and African states (notably Argentina, Chile, and Chad) have offered some relief to survivors and victims’ families by putting perpetrators on trial and sentencing them.

A vital part of this lesson is that there will be no hope of justice for those slain. The operating logic and wisdom is that the JVP started the violence, hence they deserved what they got. This is Hammurabi’s law, an eye for an eye, multiplied exponentially. Anti-government rebellions are not unique to us. Both Africa and Latin America have experienced them considerably. But a number of Latin American and African states (notably Argentina, Chile, and Chad) have offered some relief to survivors and victims’ families by putting perpetrators on trial and sentencing them.

But these are vital lessons the myopic Sri Lankan state will never learn. In this respect, Sri Lanka’s record is abysmal. Instead of national reconciliation or fair trials, we have former torturers and killers walking around boasting that they saved the country from disaster.

The math is simple. The death toll from both JVP rebellions and the LTTE-led Eelam Wars is estimated to be over close to 200,000. If we take only the combatants, the figure would still be very high. Most of those killed were young. Almost all had studied up to GCE O level or A Levels, some were graduates. If we take an average ten years of schooling for each, and work out the cost in per capita terms (this was an era when the state invested honestly in free education), it becomes clear why the country remains underdeveloped. Apart from the loss of brain power (however misguided their motives may have been, one can’t deny that rebellious thought is a general indicator of drive for change, initiative, risk-taking and innovation), the state lost its investment in many thousands of citizens, and more state resources were wasted in hunting them down.

It’s a self-consuming state of affairs. The macabre logic behind the carnage required that anyone who got in the way of the killing machine had to go. The case of Police Sub Inspector Rohitha Priyadharshana of the Sapugaskanda Police station is an example. This conscientious officer objected to the way suspects were summarily executed. He was abducted by a special police unit and his body was later found floating in the Kelani river, leading to the loss of a rare policeman who followed his conscience and moral repugnance of extra-judicial murder, someone who could have set an example to the police force.

"The first volume had so much detail that one would have believed it to be conclusive. But, as the second volume shows, there were many more related stories waiting to be unearthed"

In this case, the state executed one of its own subordinates whose training has cost the tax payer a considerable amount of money.

The JVP in turn murdered many academics, intellectuals, and other professionals, as well as police and military personnel. Only a few of these shadowy assassins were ever identified. While Vijaya Kumaratunga’s killer was identified, those who killed TV announcer Sagarika Gomes or song writer and broadcaster Premakeerthi de Alwis remain identified only as ‘JVP.’ Nor has the political party by that ever offered an apology for those killed by its cadres simply for having different political views or for disobeying its draconian laws during the days of mayhem.

This writer believed, and still does, that if the JVP had succeeded, its leaders would have chosen the Maoist-oriented Pol Pot path of destruction. But that isn’t an excuse for accepting Hammurabi’s Law as the best way to deal with extreme political dissent. Accepted wisdom is that the state’s ferocious counterattack was necessary because the law and order machinery was weak and in danger of being overwhelmed by the rebellion.

The reason for this weakness isn’t lack of numbers. Even in 1989, Sri Lanka had more people in uniform on a per capita basis than many other countries. The reason was political  meddling which caused paralysis in decision making as well inefficiency plus deficiencies in training and equipment. The latter problems were again caused by politics as the government took, as it still does, the lion’s share of what is a small budget for its own benefit.

meddling which caused paralysis in decision making as well inefficiency plus deficiencies in training and equipment. The latter problems were again caused by politics as the government took, as it still does, the lion’s share of what is a small budget for its own benefit.

This situation changed during the latter stages of the Eelam War, but the result now is worse – an oversized military (relative to the country’s size and wealth), leaving vital areas such as education, health, public transport and infrastructure (forget the highways and look at the unguarded rail crossings) underfunded. It’s a perfect recipe for another rebellion at some future date, and it too, will be crushed according to Hammurabi’s Law. One wonders if what Ernst Haeckel noted so cynically back in the 19th century as this tropical island paradise’s pathological penchant for blood letting has become a part of the national psyche.

"Our politicians and some ‘think tanks’ are so keen on emphasizing on gains in per capita income and living standards while the rich poor gaps are wider now than they were in the 1980s and the human rights record remains abysmal"

The state’s unwillingness to learn and put the record right is demonstrated by the embarrassing number of show trials started with much fanfare after the ‘democratic’ change of 2015, with progress being at snail’s pace or none at all, and they will most likely be derailed after the next regime change. Where human rights cases connected to two the JVP rebellions are concerned, Sri Lanka has only one example to be proud of – that of the 1971 Premawathi Manamperi case. The evidence of a captured suspect called Kamalawathi was crucial in getting the convictions. She too, was raped, but she wasn’t executed like Manamperi.

The lesson was learnt well by those who were given a license to do as they pleased with captured suspects in successive rebellions – destroy the evidence. This simple and macabre logic, more than any other factor, would have contributed to the killing of so many captives. According to human rights sources, the death toll from the 2nd rebellion was some 67,652. Of these, 6,661 or roughly 10% were killed by the JVP, the rest by the armed forces, the police and various paramilitary groups. While many died from torture, a larger number seem to have been killed as a convenient way of getting rid of the evidence.

This becomes glaringly so in the case of female captives, a hitherto shadowy chapter which Dharman Wickremaratne uncovers in great detail. They too, faced torture but their fate was worse as they faced widespread sexual abuse. The author claims that about 2,000 female JVP members were ‘disappeared or executed’. Unlike their male counterparts, only a handful had the luck to survive and undergo rehabilitation. This terrible statistic has faced a wall of silence for three decades until exposed by the author.

The case of Ashwini Iresha Polgampola is particularly poignant and her fate puts to shame the entire machinery of ‘law and order’ and the politicians who permitted this carnage in the name of national security.

Ashwini’s father abandoned the family when she was still a child, and she was raised by an uncle. Despite this troubled childhood, she grew up to become an attractive, dynamic young woman and a bright student. As an undergraduate of Sri Jayewardenepura University studying applied science, she was recruited by the JVP, and with her natural leadership qualities and bravery, she took a very active leadership role which led to her tragic demise in December 1989.

She became part of a plot to kill the then defence minister Ranjan Wijeratne with a car bomb. This daring but hopeless plan reveals the JVP leadership’s desperation following the loss of Rohana Wijeweera. Lacking the means to detonate the bomb by remote control, it was decided to ram a bomb-laden car into the minister’s vehicle and three attempts were made in December 1989.

"The JVP and its military arm the DJV, in an insane attempt to avenge Wijeweera’s death and to achieve final victory, continued its murder and violence while the state’s security organs and other paramilitaries reacted ferociously, convinced that more and more killing would finally crush the rebellion. It did"

The car was driven by veterinarian science student Janaka Seneviratne. Ashwini went along, to give the impression of a couple and thereby reduce suspicion. The attempt failed. Both of them were arrested soon after, tortured and executed. The author says that Ashwini suffered “brutal abuses” before being killed.

These people should have faced a proper legal process instead of torture, rape and execution. Once rehabilitated, they could have been dynamic and productive in civilian life. This is part of our ‘brain drain’, not just the exodus of doctors, engineers and IT developers. When Ranjan Wijeratne was questioned in parliament about their fate, he lied that they had escaped custody. Throughout human history, we find examples of magnanimous leaders like Abraham Lincoln and Simon Bolivar. Unfortunately, no Sri Lankan leader has ever shown that quality under duress (though S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike reportedly called his assailant ‘a misguided man’). On the contrary, they have applied Hammurabi’s Law.

Parallel to this shameful history, Dharman Wickremaratne devotes a chapter to the story of various presidential commissions appointed to look into extra-judicial executions and disappearances. These happened mainly during President Chandrika Bandaranaike’s tenure and, according to the author, she allowed the reports to be swept under the carpet. Some which were sent to the National Archives were mysteriously ‘misplaced.’

Our politicians and some ‘think tanks’ are so keen on emphasizing on gains in per capita income and living standards while the rich poor gaps are wider now than they were in the 1980s and the human rights record remains abysmal. Being arrested even for a minor offence by the police under normal circumstances is still dreaded by millions, leave alone being arrested or abducted during a time of emergency.

Dharman Wickremaratne goes on to reveal the names of who went beyond the call of duty to murder and torture their captives. Many such sadistic figures are named in this book, and that includes a number of women personnel, too.

Finally, the story of Premkumar Gunaratnam shows how luck and personal charm sometimes permitted those taken to detention centres to survive with minimal suffering. A front line organiser and activist, he escaped captivity only to be captured again, but apparently remained popular with his captors because of personal charisma and singing ability. But most of the captives were not so fortunate.

"A vital part of this lesson is that there will be no hope of justice for those slain. The operating logic and wisdom is that the JVP started the violence, hence they deserved what they got. This is Hammurabi’s law, an eye for an eye, multiplied exponentially."

The book is stronger on factual reporting than analysis of events and personalities; perhaps the author’ proximity to the events and people he describes has robbed him of the emotional distance needed for cold-blooded analysis. But no such history can be completely detached, and that does not detract in any way from this book’s value as the most comprehensive history of the JVP’s sometimes brilliantly executed but ill-judged 2nd rebellion we have to date.

It also brings into serious question Sri Lanka’s record as a functional democracy when the status quo is threatened by internal dissent, as well as the prevailing, politically sanctified school of thought that the Buddhist way of life tempers people into ‘grace under fire.’ As most of the victims, as well as their tormentors, were Buddhists, this bloody record clearly refutes that claim.

Mobile Phone /viber: 071-2733986, 011-5234384/ 3108687,

E-mail: [email protected]

facebook.com/DharmanWickremaretne