Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

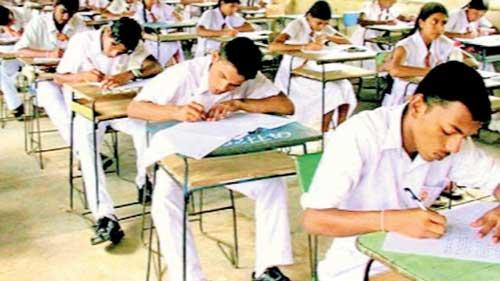

Over the past few days, the government’s notice to have the already postponed GCE Advanced Level examination  in September triggered much discussion. When it was issued, the scheme was to hold the examination between September 7 and October 2. Segments of the teaching community – including private tutors – trade unions, and student groups fielded opinion against this. Their concerns were shared with the public through media briefings and social media. Most recently, the Minister of Education was reported as having directed the relevant education officials to “consider the requests” of all concerned parties.

in September triggered much discussion. When it was issued, the scheme was to hold the examination between September 7 and October 2. Segments of the teaching community – including private tutors – trade unions, and student groups fielded opinion against this. Their concerns were shared with the public through media briefings and social media. Most recently, the Minister of Education was reported as having directed the relevant education officials to “consider the requests” of all concerned parties.

"On the other hand, the trauma and confusion caused by an interrupted academic programme cannot be “set right” by adding days to the tail end of the course"

Ideas expressed at a press conference by the Joint Teachers Service Union (JTSU) seemed to summarise the case for teachers and students who opposed the September date. Speakers at this briefing laid emphasis of the long closure of schools experienced in 2019 and 2020—first as a result of the Easter bomb attacks, and later due  to the Covid pandemic. Speaking at the JTSU press conference, activist Sanjeewa Bandara calculated almost 80-85 working days having been lost due to these twin crises. Concerned parties suggest that the run-up to exams should consist of a time frame that compensates to a day the time that was lost. Their argument follows that between July and September there is insufficient preparation time to revise the curriculum ahead of what is arguably Sri Lanka’s most competitive public exam.

to the Covid pandemic. Speaking at the JTSU press conference, activist Sanjeewa Bandara calculated almost 80-85 working days having been lost due to these twin crises. Concerned parties suggest that the run-up to exams should consist of a time frame that compensates to a day the time that was lost. Their argument follows that between July and September there is insufficient preparation time to revise the curriculum ahead of what is arguably Sri Lanka’s most competitive public exam.

"It is unlikely that work missed (or untaught) over several pandemic-ridden weeks would leave the student handicapped for the rest of their life"

But, why must the government haste in holding this all-important, future-defining exam at short notice? After all, as Upul Sannasgala—a renowned private tutor of yesteryear cum cultural critic—reminded in a ‘live-streamed’ discussion, the next cycle of A/L students are not due for admission until April 2021. Therefore, the government was not pressured for time, and the concerns of all stakeholders could be reasonably assessed. But, from the state’s point of view, holding the exam in September—or, at the earliest convenience—achieves two ends which are crucial to government and administration. An early examination, primarily, sends out a signal to the wider society of normalcy returning to our socio-cultural and economic apparatuses which, since March, have been clouded by uncertainty. Of equal importance, the immediate scheduling of exams, as a symbolic gesture, demonstrates in the government decisiveness and a frontline role in chaotic times like what we live through at present.

"Ideas expressed at a press conference by the Joint Teachers Service Union (JTSU) seemed to summarise the case for teachers and students who opposed the September date"

But, on the other hand, with elections coming up, the government will also be cautioned to take into account the grievances and distress of the education sector. Even if the current A/L student body doesn’t feature in the electorate, members of the teacher service and family members of students and teachers are significant enough to play a decisive role in an election outcome.

Some leading private tutors of the country—with good networks among them—openly canvassed for President Rajapaksa in his successful run for office in November 2019.

"An early examination, primarily, sends out a signal to the wider society of normalcy returning to our socio-cultural and economic apparatuses which, since March, have been clouded by uncertainty"

From my point of view, the call for additional time to compensate for time lost—a number of days equal to the number of days lost—is an unimaginative demand. In both the call for elections as well as the A/L examinations, the government has demonstrated a certain urgency to “move on”. It is unlikely it will suddenly become generous and relax its push for momentum.On the other hand, the trauma and confusion caused by an interrupted academic programme cannot be “set right” by adding days to the tail end of the course. As phenomena, trauma and displacement are more complex.

"From an academic point of view, the purpose of the A/L exam is to prepare the student for higher studies and to provide a benchmark for university entrance"

A fruitful discussion base—or, a plausible solution—can be worked on a realistic timeline to hold exams at the earliest convenience. But, this discussion requires flexibility and reasonableness from both sides: the protagonist and the antagonist. With the exceptional circumstances in view, practical considerations are in demand. One such approach can benefit from gauging the feasibility to hold exams under a revised pool of topics for each subject.

Under such a scheme a subject runs the risk of falling short by two or three themes. But, the A/L assessment, in any case,is carried out through the examination of selected topics.

"A fruitful discussion base—or, a plausible solution—can be worked on a realistic timeline to hold exams at the earliest convenience. But, this discussion requires flexibility and reasonableness from both sides: the protagonist and the antagonist"

The full scope of the curriculum is rarely projected in the final paper. From an academic point of view, the purpose of the A/L exam is to prepare the student for higher studies and to provide a benchmark for university entrance. It is unlikely that work missed (or untaught) over several pandemic-ridden weeks would leave the student handicapped for the rest of their life. It is more likely that some of these sections will be revised or referred to in some way—if not, deconstructed and discarded—as a footnote of a dull university lecture.

The philosophy in demand is of the rain-affected game: to revise the number of overs and to change the fielding restrictions. It wouldn’t exactly be your ideal game of cricket, but you will still ensure there’s a game to watch and play.