Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

“I like the religion that teaches liberty, equality and fraternity.”

~B. R. Ambedkar

When, in 1956, S W R D Bandaranaike unleashed the power of the saffron robe, he did not realise that he was setting free a cultural force that Ceylon did not know it had within itself, a force that had total control over the generally docile mind of the Sinhalese Buddhist. Whether or not the country was under colonial rule for nearly half a millennium, whether or not the Portuguese, Dutch and the British guns and mortars played havoc around the large city centers, whether or not the vulnerable denizens along the coastline of the country converted to Christianity and Catholicism, some through sheer fear of the guns or easily saleable concept of omniscient and omnipotent ‘God’, those whose abodes were in the far corners of the land, Sinhalese Buddhists kept their faith in a philosophy and a way of life as preached by Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. That faith’s sustainability powers were much more powerful than the colonial guns and mortars; that faith’s lasting quality was much more sublime and serene than the fairytale character of the Bible and the five books of the Torah.

When, in 1956, S W R D Bandaranaike unleashed the power of the saffron robe, he did not realise that he was setting free a cultural force that Ceylon did not know it had within itself, a force that had total control over the generally docile mind of the Sinhalese Buddhist. Whether or not the country was under colonial rule for nearly half a millennium, whether or not the Portuguese, Dutch and the British guns and mortars played havoc around the large city centers, whether or not the vulnerable denizens along the coastline of the country converted to Christianity and Catholicism, some through sheer fear of the guns or easily saleable concept of omniscient and omnipotent ‘God’, those whose abodes were in the far corners of the land, Sinhalese Buddhists kept their faith in a philosophy and a way of life as preached by Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. That faith’s sustainability powers were much more powerful than the colonial guns and mortars; that faith’s lasting quality was much more sublime and serene than the fairytale character of the Bible and the five books of the Torah.

A Buddhist committed himself to the five precepts and a simple way of life; his loyalty to the teachings was not blind as the Teacher Himself taught the disciples not to believe in a frail ‘soul’; as such a soul was the very basis of Hinduism, Buddhism’s predecessor, Buddhism itself had to contend with a competing set of theories of Brahma, it’s creations, his avatars such as Vishnu, Ganesh etc. ‘Popular Hinduism’s’ corrupting influence on Buddhism grew exponentially, once again as ‘Popular Hinduism’s’ allegiance to unseen and unknown ‘God’ did enjoy polarizing exploit among the uneducated masses. Its influence corrupted the composed mind of the average Buddhist to such an extent, he started paying ‘pooja’ to gods in the name of Kataragama, Vishnu, Saman, Pattini, etc. in order to attain his mundane needs; he offered, first hundreds and then thousands of rupees along with the ‘pooja wattiya’ (rattan bowl), instead of practising Karuna, Metta, Muditha and Upekkha and the five precepts.

It was to this convoluted mindset that Bandaranaike appealed. Politics in all its inner bearings is fundamentally cynical; its divisive character and its polarizing capability could motivate and move any docile man or woman to the brim of violence. The loyalty and fidelity it demands of its practitioner and follower are limitless. Its corrupt and corrupting character attract many an unwise man to itself in such a ferocious fashion, the practitioner or the follower does not realise until its all-consuming power has totally enveloped his fragile mind and eaten into the very fabric of decency that sets man from beast.

Bandaranaike, being schooled in Classics at Oxford, the ‘Taxila’ of the modern world of education, in the early nineteen hundreds, fully understood the undertones of religious fervor that could control and regulate an undisciplined and uneducated mind of man. He, unlike his contemporaries at the time, realised that the half-a-millennium colonial rule had had its benumbing effects on the large masses in Ceylon. He also knew that, if he could find some leading Monks, he would be in an enviable position to exploit the burning religious amber and turn it into a political fireball.

Unfortunately, both for Bandaranaike and the country at large, the leading monk came in the form of Mapitigama Buddharakkhitha, who was inherently dishonest and deeply immoral, a typical antithesis of a pious man in the saffron robe who in ancient times was reckoned as a man of wisdom and intelligence. Wisdom and intelligence apart, Buddharakkhitha possessed enormous personality and the charisma he was swathed in was more than sufficient in the context of a political campaign a leader would have been pushed to carry out in an extremely volatile environment.

Buddharakkhitha did not see any negative qualities in himself; he used his political and social minuses he was weighed down with as positively advantageous pluses for consummating his nefarious ‘deals’. A culture that was intrinsically flawed, a behavioral pattern on the part of Buddhist Monks which was inherently dangerous and potentially catastrophic was experiencing its birth pangs in the late 1950s. Religion, specifically Buddhism organised along the lines of a hierarchical clergy, became an integral part of any government formed under the leadership of the Bandaranaikes and Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). This was further strengthened by the 1972 Constitution wherein a sperate clause was inserted rendering special status for Buddhism.

Racial-religious riots

All these developments led to a ‘culture of influence’ by the Buddhist Clergy on the policies and programs adopted by the government. The scope of this influence was not limited to religion; it spread across the socio-economic boundaries thereby became a mitigating effect on those who occupied higher political offices in the country. Racial-religious riots that erupted through the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s were a direct aftereffect of this culture that Bandaranaike/Buddharakkhitha duo gave birth to.

Agitation by the Northern Tamils, firstly led by S J V Chelvanayakam and his Federal Party (FP) that later developed into Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and secondly by Amirthalingam and Company became a lightning rod for the civil riots that later graduated to a full scale war and a military confrontation between the Security Forces of the country against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) and its leader Velupillai Prabhakaran.

The massacre of Buddhist Monks in Arantalawa ignited the anger and ferocity among Sinhalese Buddhists; this hereto docile civil population became an unarmed guardian of the Dhamma so pure and anti-violence; their anger turned into hatred of anyone Tamil and Tamil-speaking. The resulting confrontation was so unforgiving and venomous, all that modern terms such as racial profiling, racial genocide were confined to the English-speaking Colombo-educated pukka sahibs. Sinhalese exceptionalism became Sinhalese tribalism. And it was the Buddhist Clergy who led the way right through.

The thirty-year war was only the culmination point in this vicious process. The religious groups became so intertwined in the political process; they became the leaders in some of the agitational activities organized by the civil organizations in the country.

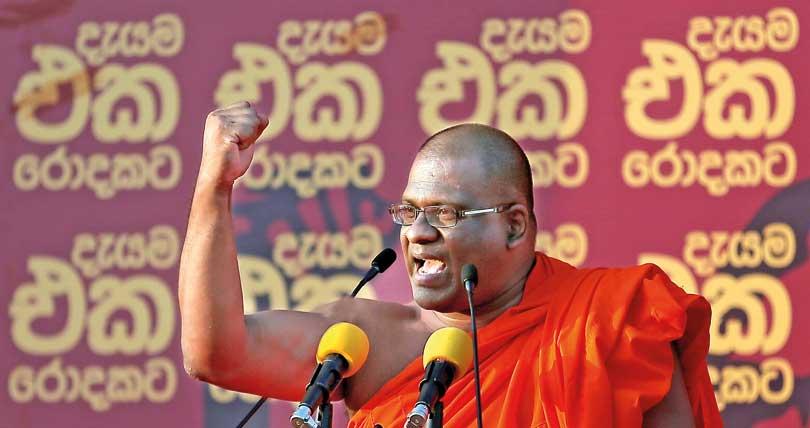

Ven. Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara Thera, who looks and acts more like a petty ruffian wrapped in a saffron robe rather than an ordinary Buddhist Monk, with express nod of the Rajapaksa regime rose to prominence chiefly thanks to the development of the culture so nursed and consummated by the Bandaranaike/Buddharakkhitha combination at the beginning.

But the most tragic aspect of this phenomenon is the deliberate and unwise policy of the current President, Maithripala Sirisena. When Gnanasara was imprisoned as punishment for defiling the Law of the Country, Sirisena released this charlatan on the basis of a Presidential Pardon. All of a sudden, Gnanasara who was nearly forgotten by those who sought violence and mayhem as an instrument of expression, became a hero again. The arrogance of the fellow reached incredible levels and he began dictating to those who belonged to Islam faith as to how to practice their religion.

Gnanasara does not belong in the civil society. Nor should he be allowed to represent the uplifting teachings of Buddha. His very presence is enough to desecrate its supreme measure and purity of non-violent men and women. But the those who believe in law and order and democratic principles are caught in a grip of a dilemma: silently suffer the consequences or organize another group of Buddhist Monks and face the accusation of Sanga-bēdha (division of the Clergy). Whichever they choose, it’s not a good choice.

Gnanasara has some influence; his scope of work is much more widespread than before. The influence he exerts cannot be underestimated and if one does it, he does it at his own political peril. Easter Sunday Massacre engineered by some Muslims only helped worsen the situation. All signs of dissatisfaction about the current regime are present. To add fuel to fire, all statements emanating from the government politicians are even more depressing. A culture that was born out of political necessity has consumed a susceptible populace; its beginnings were ominous and its end seems to be far, far away.

(The writer can be contacted at [email protected])