Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

“The new Sinhala nationalist political project”, which he views as being disdainful of democracy and being buttressed by “faith in a strongman”

We come across a coincidence of authoritarianism and efficiency which not even his band of brothers has equalled

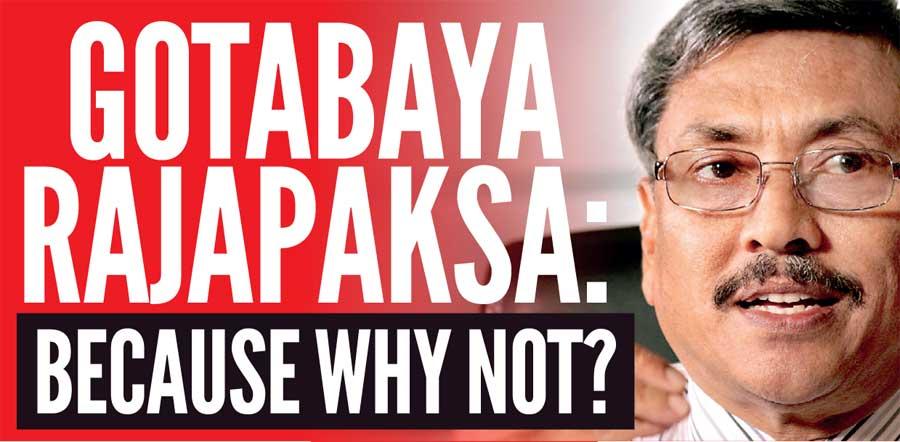

arim Peiris, in an article on Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidential ambitions (“Sinhala nationalist critique of democracy – a mistake”), conflates the man’s candidacy with what he refers to as “the new Sinhala nationalist political project”, which he views as being disdainful of democracy and being buttressed by “faith in a strongman.” After a series of extrapolations, contentions, and conclusions about the Rajapaksas, he lays his argument bare for all to see, read, and savour:

arim Peiris, in an article on Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidential ambitions (“Sinhala nationalist critique of democracy – a mistake”), conflates the man’s candidacy with what he refers to as “the new Sinhala nationalist political project”, which he views as being disdainful of democracy and being buttressed by “faith in a strongman.” After a series of extrapolations, contentions, and conclusions about the Rajapaksas, he lays his argument bare for all to see, read, and savour:

“... irrespective of the candidates, the basic political formulae of the Rajapaksa clan verses the rest would still pose a significant political challenge to the Rajapaksa comeback project, and the resultant diminution of Sri Lanka’s democratic, civil and political rights.”

Put very simply, even the possibility of a Rajapaksa comeback, which Mr. Peiris unequivocally describes as an elected dictatorship, would, if unchecked, turn into a “fascist experiment” that presumably will end in another Holocaust. (Whether it will lead to another world war, though, Mr. Peiris does not elaborate. In any case, we get his message: a vote for Gotabaya is a vote for the end of the country as we know it and, in all probability, a vote for a Sinhala Buddhist Fuhrer.)

Gotabaya Rajapaksa did not help himself when he brushed off remarks made by a chief prelate that the country needed a strongman, even if that strongman happened to be another Adolf Hitler. He did not help himself when he marginalised the errors and lapses of commission and omission which he presided over at the Urban Development Authority.

His authoritarian streak speaks volumes for the ruthlessness he is willing to resort to in order to achieve something. He is no Hitler, nor a Caligula, but in him we come across a coincidence of authoritarianism and efficiency which not even his band of brothers has equalled. He is a poster boy for hardcore nationalists.

But critics of a Gotabaya Rajapaksa candidacy and (“Heaven forbid!” I hear these critics screeching) presidency are getting their arguments wrong and, worse, muddled up. These misconceptions rest on what these writers assume will happen IF the man enters the race, and IF he wins.

"Gotabaya Rajapaksa did not help himself when he brushed off remarks made by a chief prelate that the country needed a strongman, even if that strongman happened to be another Adolf Hitler"

Those assumptions in turn rest on extrapolations from the past: he is alleged to have done this, so he will continue doing that if he is elected. He is not to be given the benefit of the doubt, for to give him that would be to assume that he is capable of redemption, when he is not.

Because of this, every speech he gives, every act he stages, every press release he or his brothers issue to the public, are censured as shows of cosmetic expedience. Since he isn’t in power, he’s rebranding himself with a headline Shyamon Jayasinghe sees as “a well crafted marketing slogan for a prospective Presidential candidate”:

“How can we have freedom without discipline?” Mr. Jayasinghe’s take on it is simple: “The problem about all this is that a marketing programme must match with reality. Gota’s doesn’t.” There’s much in that argument to disagree with.

The premise which the critics of Project Gotabaya choose to argue against is that while the present government has hic-cupped with respect to the promises made to the people, “the  answer must be, as declared in January 2015 by the rainbow coalition, for democracy to be strengthened and for good governance to be established.” But Mr. Peiris, in making his case for good governance, undermine his own argument by conceding territory to the yahapalanists through a reference to a remark made by one of the biggest campaigners for the coalition government.

answer must be, as declared in January 2015 by the rainbow coalition, for democracy to be strengthened and for good governance to be established.” But Mr. Peiris, in making his case for good governance, undermine his own argument by conceding territory to the yahapalanists through a reference to a remark made by one of the biggest campaigners for the coalition government.

“It was State Minister of Finance Eran Wickramaratne, who during the abortive 52-day Rajapaksa regime late last year, stated that the current political set up served only the rulers and not the governed. He was speaking to a group of professionals and was arguing for taking governance from populists to professionals. This same argument was the basic rallying cry of the rainbow coalition of 2015, which built a socio-political movement on good governance and consequently challenged and overthrew the president who ended the war.”

The dichotomy is between the professionals and the populists, between the good and the bad. The problem is that G. B. presents a paradoxical combination, of strongman authoritarianism and Gaullist charm, that makes it difficult for us to square his image, rebranded or not, with the professional/populist or good/bad binaries.

Project Gotabaya, as I have noted many times before in this column, appeals to a disparate set of milieus, ranging from the rural farmer who sent his child to fight the war to the urban bilingual professional from Borella, Kirulapone, Maharagama, and Mount Lavinia. Its base is Sinhala Buddhist, but it is also Sinhala (Buddhist and non-Buddhist) AND Buddhist (Sinhala and Olcott).

That is why there are non Sinhalese Catholics and urban middle class Buddhist entrepreneurs who profess admiration for him and back him. They don’t see him as the redeemer of the nation the extreme nationalists see him as, but they are willing to hedge their bets on him, because of ideological considerations and also because the way the country is being run is not conducive to their interests.

"Gotabaya does not conform to a particular label. This is because he is ideologically rudderless; his bases are, ethno-religious identity, and, on a superficial level, cultural modernity"

Gotabaya engages with his enemies by resorting to his enemy’s weapons: the Ranil-Mangala-Malik trio, for instance, has Razeen Sally, so the Rajapaksa cohorts “have” Howard Nicholas. This identification with the enemy has begrudgingly been accepted as a necessity by the Jathika Chinthanaya camp, though since of late even they have begun to criticise it (especially the likes of Nalin de Silva, who tend to view Mahinda, the favoured brother, as the more viable candidate). And yet, even with this the man has achieved the seemingly impossible: reconcile the Sinhala Buddhist nationalists with the Olcott Buddhist cosmopolitans.

What brings these groups together, incidentally, is not a “disdain of democracy” as Mr. Peiris seems to think, but dissatisfaction with a government that has, in their view at least, sacrificed almost everything at the altar of neo-liberalism. In other words it’s not only proponents of a “Sinhala nationalist political project” who are backing Gotabaya; it’s also a myriad of other forces, too complex to enumerate here.

Contrary to what critics from the nationalist and anti-nationalist camps will have you think, moreover, Gotabaya does not conform to a particular label. This is because he is ideologically rudderless; his bases are, on the one hand, ethno-religious identity, and on the other, on a superficial level, cultural modernity.

These twin strands of an incongruous presidential hopeful have been an advantage to Gotabaya. They celebrate the identity of the majority, concurrently (Sinhala and Buddhist) and separately (Sinhala or Buddhist); with the gospel of development, they also adhere to the ideal of growth plus equity. In other words, they represent a blend of populism and professionalism, of discipline and freedom.

The issue with critics of Gotabaya in this respect is that when you try to separate populism from professionalism, you are assuming that the polity can be divided into two camps, when they cannot.

"They don’t see him as the redeemer of the nation, but they are willing to hedge their bets on him, because of ideological considerations and also because the way the country is being run"

This has been complicated by the fact that Gotabaya, more than Mahinda and Basil, panders to neither; he can be a populist or a pundit. It depends on when you choose to wake up: in the morning, when he is a rabble-rouser, or the evening, when he is a visionary. The likes of Mr. Peiris prefer the morning; the likes of Nalaka Godahewa prefer the evening.

So whether it’s the freedom/discipline dichotomy or the professional/populist dichotomy, the critics of Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Project Gotabaya seem to have failed to come to terms with one salient fact: predictions of gloom and doom for the country, in the form of a Holocaust (Mr. Peiris) or a Damocles sword (Mr. Jayasinghe), will matter very little to those who choose Gotabaya.

All that matters will be whether he is the strongman who brings about national development and resurgence; this will cut across ethnic and religious lines, as it should.

In that sense, flawed though his campaign is according to Mr. Jayasinghe, he has won half the battle: he has got his critics to rationalise the election as a conflict between democracy and destruction, when his programme promises everything for everyone: to nationalists, as well as to more moderate sections. It isn’t an “either/or” contingency the man is targeting; it’s an “everything with everyone” contingency. That, strangely and tragically, seems to have been missed by his detractors.