Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Some seven decades ago, added to the political lexicon was a Sanskrit term called Pancha Sheela or Panchsheel. Literally, it means five principles, but when applied to international relations the term assumes greater significance. It is a mantra that can keep nations at peace and conflicts at bay.

Some seven decades ago, added to the political lexicon was a Sanskrit term called Pancha Sheela or Panchsheel. Literally, it means five principles, but when applied to international relations the term assumes greater significance. It is a mantra that can keep nations at peace and conflicts at bay.

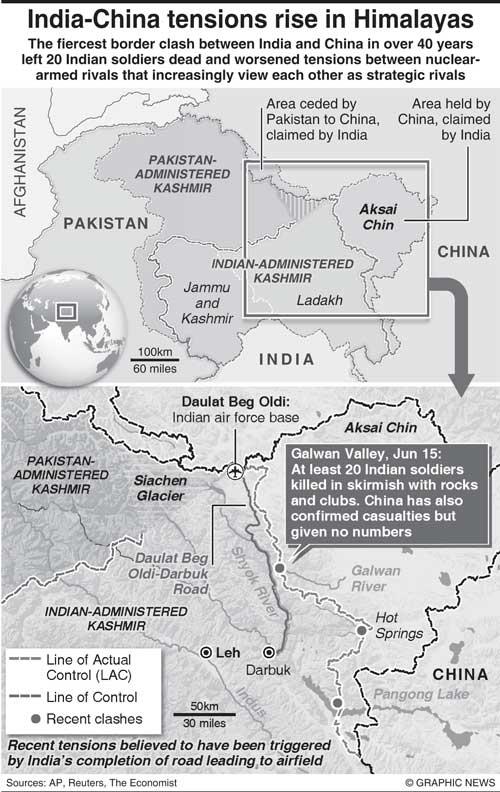

Significantly, China and India -- which have been embroiled in border clashes in the past few weeks in the Himalayan region -- were credited with bringing the term to international politics through a bilateral treaty in 1954. However, after eight years they binned the hallowed principles and waged a border war. Notwithstanding the 1962 Sino-India war, the Pancha Sheela remained the moral force of the Non-Aligned Movement during its hey days.

The Pancha Sheela principles affirmed (1) mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; (2) mutual non-aggression; (3) mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; (4) equality and mutual benefit; (5) and peaceful co-existence.

A few days after the two countries signed the 1954 treaty in Beijing, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited Colombo for the Asian Prime Ministers’ Conference and reaffirmed the commitment of India and China to Pancha Sheela. His statement came against the backdrop of border disputes between two countries over Aksai Chin region and a territory which China calls South Tibet and India Arunachel Pradesh.

Nehru said in Colombo: “If these principles were recognised in the mutual relations of all countries, then indeed there would hardly be any conflict and certainly no war.” The territorial disputes could have long been resolved, if the two countries had stuck to the Pancha Sheela. The 1962 war would not have happened. There would be no clashes between the armies of the two countries on the disputed border. The 20 Indian soldiers would not have died this week in Ladakh in clashes with Chinese soldiers. Besides, the two countries would have strengthened their ties to forge an economic alliance capable of taking Asia to the heights of development to free its teeming millions living in abject poverty to the haven of prosperity. Alas, that was not to be.

This was evident in the current tension in two border areas in Ladakh – the Galwan Valley and Pangong Tso. India says the strategic Galwan valley has been under its control; but China disputes this claim and insists the entire valley is Chinese territory. Talks were held to defuse the tension, but mutual suspicion of each other’s activities in the area led to clashes that were fought with nail-studded clubs and rocks. India lost 20 soldiers while China also suffered an undisclosed number of casualties.

The territorial dispute was not India’s making. Neither was it China’s. Like the Kashmir issue, the Palestinian issue and many other international issues that have led countries to war, the Sino-India territorial dispute was also a British made one during Britain’s oppressive colonial rule in the subcontinent.

The border demarcation through the so-called McMahon line and several colonial era accords are still a contentious issue, for it involved neither India nor China as stakeholders. However, after the post-World War political turmoil in China and India, the two nations after their liberation struggle victories in the late 1940s wasted no time to launch the process to amicably solve the border disputes. But one bad decision led to another and the two countries began to view each other’s moves with suspicion, leading to the 1962 war.India’s then Defence Minister, the much-respected statesman V.K. Krishna Menon, was blamed for India’s defeat. He was forced to resign. Since then, China has been an enemy in the collective Indian mind, notwithstanding several positive measures the two countries continue to take to improve diplomatic and economic ties. Significant among these moves was the ground-breaking visit of the then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to Beijing in 1988 for a meeting with the then Chinese leaders. It was the first such meeting after the 1962 war.

During Gandhi’s historic visit, the two countries revived their commitment to find a solution to the boundary issue in keeping with the Pancha Sheela spirit. Though there was willingness on the part of the two countries to improve ties, the rapidly changing international political situation of the early 1990s and later the emergence of right-wing nationalist politics in India made reconciliation difficult.

The adage that in politics there is no permanent friend or foe, only permanent interest does not apply to nations tainted by ultra-nationalism. Ultra-nationalism needs enemies to survive and remain in power. Ultra-nationalism thrives where people live in fear of an enemy -- perceived or real. If there is no fear, ultra nationalism feeds fear and xenophobia. Its advocates create enemies either across the border or portray a minority group within the country itself as an enemy within.

India today is a classic example of this ultra-nationalism, with members of minority communities being meted out mob justice by right-wing racist groups, the key vote base of the ruling Bharatiya Janatha Party, which has spurned the secular, rights-based political order the country’s constitution promotes.

Thus it comes as little surprise, when a BJP minister this week called on the government to ban Chinese restaurants. Some people showed their anger by breaking made-in-China products and called on the government to impose economic sanctions on China. With ultra-nationalist politicians encouraging such conduct and rhetoric to cover their blunders and failures in bringing the Covid pandemic under control, reviving of Pancha Sheela seems to be a distant dream.

In China, too, there is a growing perception of a hostile India. High-level Chinese officials attending international conferences such as the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore make no secret of their dislike for India. China’s close relations with Pakistan and India’s dash to come under the United States’ security orbit have also exacerbated mutual suspicion.

Geopolitics is also another issue that has pitted the two countries against each other. Caught in this geopolitical crossfire are India’s neighbours such as Sri Lanka, Nepal and the Maldives, countries where China’s investments have seen a meteoric rise in recent years.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi was to hold an all-party videoconference yesterday to discuss the crisis. This comes as the two countries have stepped up measures to defuse the tensions while warning the other of dire consequences if there is further violence. Modi said, “India wants peace, but, if provoked, India is capable of giving a befitting reply.” Beijing said in turn that India should not underestimate China’s firm will to safeguard its

territorial sovereignty.

During the 1962 war, Sri Lanka played a peacemaker role to end it. Should not Sri Lanka make use of its privileged status as the friend of both India and China and play the peacemaker role again and urge the two countries to take another look at the long forgotten Pancha Sheela?