Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

he decomposed body of a 32-year old RTI activist who went missing in January was found in Pune, a city in the Indian State of Maharashtra early February. Such is the plight of a movement that was initiated to transfer power into the hands of the people. The Right to Information Movement inIndia began with the MazdoorKisan Shakthi Sangathan (MKSS) that fought to bring transparency into villages via the demand for minimum wages. The Movement founded by Aruna Roy believed that without information to people, there’s no democracy. Its efforts to find loopholes in a corrupt system bore fruit when the RTI Act was enacted on October 12, 2005. However, a struggle of 14 years, is now dying a slow death as crores of RTI applications and cases are pending to be processed and disposed. Adding to the chaos is the unethical appointment of former civil servants as Information Officers which is a breach of Sections 12 (5) and 15 (5) of the Central RTI Act.

he decomposed body of a 32-year old RTI activist who went missing in January was found in Pune, a city in the Indian State of Maharashtra early February. Such is the plight of a movement that was initiated to transfer power into the hands of the people. The Right to Information Movement inIndia began with the MazdoorKisan Shakthi Sangathan (MKSS) that fought to bring transparency into villages via the demand for minimum wages. The Movement founded by Aruna Roy believed that without information to people, there’s no democracy. Its efforts to find loopholes in a corrupt system bore fruit when the RTI Act was enacted on October 12, 2005. However, a struggle of 14 years, is now dying a slow death as crores of RTI applications and cases are pending to be processed and disposed. Adding to the chaos is the unethical appointment of former civil servants as Information Officers which is a breach of Sections 12 (5) and 15 (5) of the Central RTI Act.

In this backdrop, the Daily Mirror takes a closer look at the effective use of RTI in Sri Lanka and India.

Even though it’s at its infancy, two years after Sri Lanka’s RTI Act has been enacted, the country seems to be making slow progress in the right direction. Or so believes those who have worked tirelessly to get the Act in place. Now that it has been enacted, the media and the common man are equipped with a powerful tool to challenge a corrupt system. Except for a handful of journalists, RTI is not yet popular among the media fraternity owing to various reasons, one being the fact that they would receive information within a fortnight. Hence seniors in the RTI Movement believe that there exists a certain degree of lethargy and cynicism when using RTI – a case similar to that in India when RTI was at its infancy.

According to ‘Reflections on Sri Lanka’s RTI Act and RTI regime’, a recent publication of the RTI Commission (RTIC) of Sri Lanka, as at the end of July 2018, the RTIC is reported to have rendered 610 decisions out of a total of 839 fully-fledged appeals filed with the Commission during the past two years. This amounts to a case disposal rate of approximately 73% within the first two years. The RTIC website states that the subject matter of appeals ranged from inter Alia, problems in service delivery in government institutions, irregularities in governance processes, accountability of state institutions, requests for reports of commissions of inquiry and draft laws, to major corruption scandals in frontline state institutions.

At present, Sri Lanka is witnessing a positive period in terms of enacting the Act. But much needs to be done in order to make progress. For example, there exists a lack of full comprehension and appreciation in the public sector where the rule is to disclose information. On the contrary, what began as a people’s movement to fight corruption has gotten stuck in the gutters of a corrupt system as activists in India struggle to keep its momentum.

"At the end of July 2018, the RTIC is reported to have rendered 610 decisions out of a total of 839 fully-fledged appeals filed with the Commission during the past two years"

From modest beginnings from the villages of Rajasthan, the success of MKSS has been a source of inspiration for activists in India and across the world. The Movement later sped across India and more people were encouraged to file RTI applications and look for answers within a corrupt system. The activists of this Movement started off at grassroots level, directly interacting with the common man to tell him that he actually has the power to question the government. Numerous hunger strikes, protests and campaigning created ripples in a system that was feeding on corruption.

When the Act was enacted in 2005, the activists saw light at the end of the tunnel. As much as it was deceiving, successive governments haven’t put in a satisfactory effort to make people realize that they have a powerful tool at hand. As the number of murdered RTI activists has risen to 67, those actively involved in the fight believe that it’s the Modi Government that needs to ‘act rightly.’ This demand comes in strongly as the Central Information Commission itself is clogged with approximately 2.41 crore cases which need to be processed.

In Kerala, D. B. Binu was the first individual to file an RTI application. A high court lawyer and general secretary of the Kerala RTI Federation, Binu has engaged in a tireless war against corruption for about 20 years. He used RTI to expose the misappropriation of the tsunami relief fund in 2006, thus creating a flutter in the system. Today, however with many pending cases yet to be processed, Binu and RTI activists all over India are watching the system closely. “The pendency of Second Appeals and Complaints before the State and Central Information Commissions are practically delaying the disclosure of information beyond the prescribed time limit of 30 days,” Binu said in an interview with the Daily Mirror. “The Right to Information Act, 2005 in India is silent about the time period for disposing Second Appeals and Complaints by

the Commission.”

Even with a 100% literacy rate RTI and e-governance in Kerala doesn’t seem to be going hand-in-hand. According to Binu, in most states including Kerala, the online portal for receiving applications has not yet been set up. On the other hand, there is also an issue when recruiting information officers and training them for the job. In fact they seem to be the first ‘roadblock’ in most cases as they either don’t respond or would provide incomplete information.

As many as 67 RTI activists have been killed from 2005, since the Act came into place in 2005. “There is always a risk in being an RTI Activist in a country like India,” he stressed. “The same is inevitable until the society becomes safer for people in general. The Mechanism created by the Central and State Governments have failed many times to protect the activists. It is a sad state of affairs that people are being killed when they bring out the truth.”

Kerala SIC refuses to comment

It is the duty of the State Information Commissioner to receive and inquire into complaints from persons aggrieved by any of the reasons given under Section 18 (1) of the Act. As the process gets delayed and more activists are being killed, it is the sole responsibility of the SIC to provide cover.

When contacted, the State Information Commissioner of Kerala Vinson Paul refused to comment on any of the above matters. Furthermore, the Daily Mirror was told that there is no compensation scheme for dependents of murdered activists.

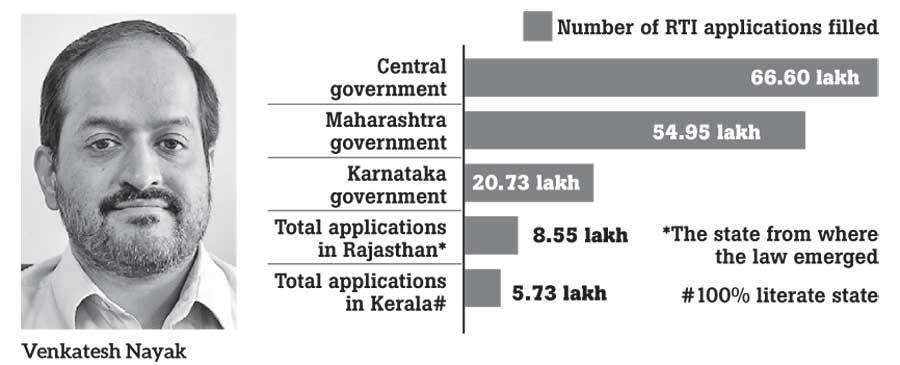

Resistance to RTI has grown : Venkatesh Nayak

“The government prefer retired officers so that they would be able to influence the decision-making process,” said Venkatesh Nayak, a prominent RTI activist and coordinator of the Access to Information Programme at the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. “It’s more of a bargaining exercise. When officials who have served long careers in the government system are being appointed, they would know how to disclose information the way the government expects. They also don’t want to bring in members of judiciary, ideally retired judges because if any information officer contravenes the law, monetary penalties could be imposed. But many of the retired bureaucrats rarely impose monetary penalties.”

When asked as to why many RTI applications are pending to be disposed, Nayak said that there are multiple reasons to it. “One of the reasons is the fact that these officers are retired bureaucrats. Another reason is the level of infrastructure where most information commissions are short-staffed and there’s less funding. When there’s a qualified staff the case will be disposed quickly. Not all information commissioners believe in disposing information rapidly.”

The Daily Mirror also learned that there is no compensation scheme for dependents of murdered activists. When asked about his opinion, Nayak further said that if there’s a compensation scheme, it means that the government accepted that its responsible for the murder of these activists. But no government wants to take this responsibility. On the other hand, the police ignores investigating into such cases.

“Resistance to RTI has grown and unless there’s a change in the way the government looks at transparency, nothing will change,” Nayak further said. “Useful information such as the process in recruiting school teachers aren’t available in the public domain. Hence there’s no accountability. If we get a wide political leadership it is possible to change India from a representative democracy to a participatory one. Unless more and more reform-minded people come into the system and work together to make the government more responsible, accountable and participatory, things will more or less remain stagnant.”