Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Morality doesn’t lack a political dimension. Political actions hence often give rise to consequences guided by unseen hands

Certain values will transcend political affiliations, whatever the government. And those values will, eventually, prevail

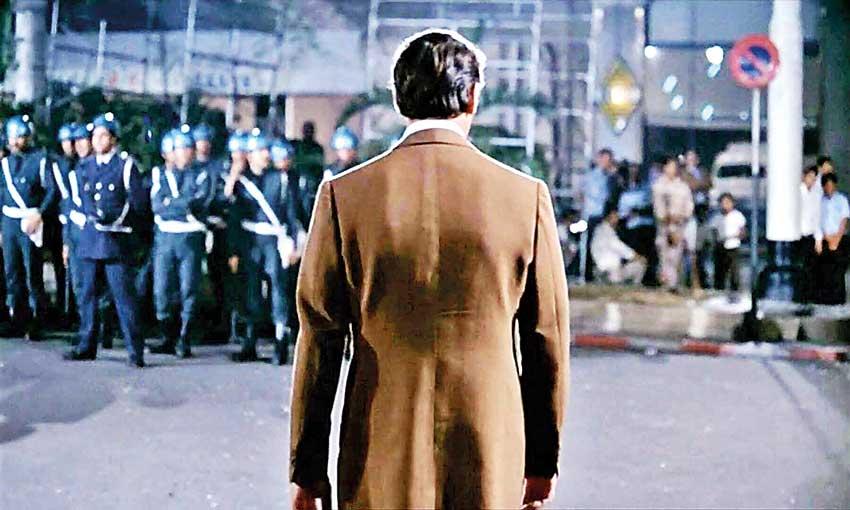

Z (1969) and The Confession (1971) are two of my favourite political thrillers. Both were directed by the great Costa-Gavras. Both are about power and the excess of power. And both are about the victims of those who indulge in the excess of power. Z is about a left-wing antiwar activist in Greece who, after speaking at a rally one night, gets hit on the head by right-wing brigands and dies hours later.

Z (1969) and The Confession (1971) are two of my favourite political thrillers. Both were directed by the great Costa-Gavras. Both are about power and the excess of power. And both are about the victims of those who indulge in the excess of power. Z is about a left-wing antiwar activist in Greece who, after speaking at a rally one night, gets hit on the head by right-wing brigands and dies hours later.

The Confession is about a Deputy Minister in Czechoslovakia who, owing to ideological disputes within the ruling party, gets arrested, tortured, and interrogated by an organisation declaring itself “above the ruling party” on the grounds of his past association with a double agent. Yves Montand, who played the victim in both, was a leftist, as were many of the cast and crew members.

More importantly, the protagonists he played were based on real people: Grigoris Lambrakis in Z and Artur London in The Confession. Neither ends in resolution: the investigation of Lambrakis’ assassination in Z provokes a crisis that culminates in the takeover of the Greek government by a rightwing military junta, while London’s release follows the fall of Stalinism that sees the arrest of many of his own interrogators. Z ends with the hero’s wife staring blankly, oblivious to the news of the resignation of the government; The Confession ends with London returning to Czechoslovakia in 1968, only to witness the Warsaw Pact invasion following a dispute between Prague and Moscow. There can be no hope. And the director cautions against hope.

More importantly, the protagonists he played were based on real people: Grigoris Lambrakis in Z and Artur London in The Confession. Neither ends in resolution: the investigation of Lambrakis’ assassination in Z provokes a crisis that culminates in the takeover of the Greek government by a rightwing military junta, while London’s release follows the fall of Stalinism that sees the arrest of many of his own interrogators. Z ends with the hero’s wife staring blankly, oblivious to the news of the resignation of the government; The Confession ends with London returning to Czechoslovakia in 1968, only to witness the Warsaw Pact invasion following a dispute between Prague and Moscow. There can be no hope. And the director cautions against hope.

And yet, hope, like life, somehow finds a way. The Greek junta did fall. The Warsaw Pact invasion did fracture the Communist movement, and it also fell, mired in enough and more contradictions, including Soviet conflicts with Euro-communist parties as well as the rise of China. Both would take place long after the films were released. Costa-Gavras’ message, however, isn’t that totalitarian regimes are doomed to fail. It isn’t that such regimes can’t lie to the people forever; it’s not the generic anti-establishment message we get from shows like HBO’s Chernobyl. His message is that certain values will transcend political affiliations, whatever the government. And those values will, eventually, prevail.

Gavras’ achievement is that he doesn’t interpret this as hostility to political action. Movies have a hard time staying away from the (fatally easy) short-cut of demonising politics and political actors. By resorting to such short-cuts, they tend to simplify history. That’s where Gavras wins. The beauty of his two masterpieces is that while one is an indictment of fascism and another of communism, he doesn’t conflate the two. He doesn’t suggest, for instance, that fascist and communist regimes are the same simply because they operate on the principle of power. Important distinctions exist, and one can’t just throw them out of the window. The anticommunists in Z, to take one example, react to the uproar over the assassination of Lambrakis differently from the way Communist authorities react to the response to the arrests of party officials in The Confession. By furnishing us with detail, we get to appreciate the complexities of these regimes. What a refreshing contrast to the empty slogans found in most anti-establishment plays here!

What the latter offer, in fact, and what movies like Z refuse to offer, is a “screw politics” worldview. “Screw politics” is a convenient copout used by activists whose refusal to engage with political action has become their undoing. Costa-Gavras’ work since Z and The Confession has varied in quality; his strongest films remain those that refuse to tell us to screw politics like that. By refusing to do so, he focuses attention on the centre, not the periphery: on the structures of power, which must be opposed, and not the holders of it, who can only be replaced. By contrast, his weaker films – those he made in the US in the 1980s, including Music Box (1989) but excluding the brilliant Missing (1980), the latter of which, long before it was proved, speculated on the CIA’s involvement in the assassination of US leftists in Chile after Pinochet’s coup – erase politics from the picture.

Thus where shows like Chernobyl fail, and where Costa-Gavras’ best work succeeds – and this is relevant to the point of my column – is the latter’s willingness to engage with politics. Chernobyl believes in political neutrality; Costa-Gavras does not. There’s nothing in Z, The Confession, or State of Siege (1972) – which stars Yves Montand as a USAID official engaging in clandestine operations against Communist insurgents – that suggests that morals operate in a politically neutral world, or that the way out is to exclude politics. Neutrality is not possible. Choices have to be made. And morality doesn’t lack a political dimension. Political actions hence often give rise to consequences guided by unseen hands: in The Confession, for instance, the protagonist’s interrogator, arrested in Khrushchev’s regime, chances across his detainee later elsewhere, and asks him what it was he did and whose orders he was following. London can’t answer him.

We can’t either.

The lesson here isn’t that politics is inscrutable. It isn’t that totalitarianism meets its end with the descent of ideology. The lesson is that no hope is possible without activism beyond parties and personalities; at the same time, however, activism of that sort must involve parties and personalities. Politics can’t be missing from the picture, and it can’t operate in a void. It has to exist, since as Aristotle put it once, we are all political animals.

However, activists today, signalling their discontent with an ideology – be it nationalism or liberalism – focus their attention on those spouting it. In other words, they want to kill the messenger, though we know killing the messenger won’t do much. The rise of Khrushchev, after all, caused a thaw in the Stalinist trials that found London guilty, yet Stalinism under a different garb raised its head after a decade, while the imprisonment of those involved in Lambrakis’ assassination didn’t prevent the rise of a more vicious junta. Still, despite history cautioning us against it, dissent, especially today, seems to me to operate on the premise that to get rid of a ruling ideology, you have to replace it with its opposite. The result as expected is a never-ending game of musical chairs.

This doesn’t happen only here of course. And yet the result of it has been that since 2015, and before, all we’ve seen take place is the overthrow of one regime and the entrenchment of another. The response to this has been as knee-jerk: get rid of the politicians and replace them with a fresh bunch. That doesn’t work either, because when the fresh bunch comes into power, those who helped them – almost invariably the same activists who ejected the old bunch – get entrenched themselves. We’ve seen this happen. Old wine in new bottles or new wine in old bottles, it doesn’t matter: either the wine or the bottles turn out to be old. The solution hence must lie elsewhere.

Towards the end of Missing, when the father of the disappeared American finally gets the truth from US Embassy officials – that his son was meddling in affairs that weren’t his concern, that the only outcome he could expect was his own murder – Costa-Gavras stops taking the side of his father, who until then believed in all sincerity that his son rebelled too much against the system, and that the system could help him. Yet when he makes the father realise the system can’t and won’t help him, Gavras doesn’t go to the other corner and offer a blanket condemnation of political action either.

The catharsis in Missing comes long before the director confirms what we knew all along – that the son has been murdered by right-wing operatives – when it dawns on the father that the system he idealised could easily betray him if his actions were inimical to its interests. Gavras places the indictment in its proper historical context, without letting it get clouded by a blanket “anything goes” hostility to politics. To be hostile to politics, to say politics is the proverbial root of all evil, is the easy way out. Gavras doesn’t go that way.

And in not going that way, he achieves what most rebels against regimes – be it Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s, Ranil Wickremesinghe’s, Sajith Premadasa’s, or even Donald Trump’s – have failed to achieve: a critique of the system which recognises that all political actors are frail, that ideology is more powerful than personalities, and that a refusal to engage with ideology will bear no fruit as far as dissent is concerned. We’ve been too occupied with the periphery – the politicians – to realise that the centre – the system, of which politicians are but one element only – eludes us. It is hence with the latter and not the former that our rebellions, and our quests for a more democratic future, must start.