09 May 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Uddika Premaratne, I’ve always felt, was born to play the down-on-his-luck defeatist. I first saw him in a Poya day TV serial years ago. I don’t remember who directed or scripted it, but I remember Uddika. Clearly. He was a cancer patient, having just received news of his imminent death, trying to make amends with his estranged girlfriend and those other acquaintances who misunderstood him, spurned him, and eventually cast him aside. To say the least, I was impressed.

I didn’t know his name at the time, but when I saw those eyes of his (for his most characteristic  feature is his eyes: half-shut, almost willingly yielding to fate), I thought I’d seen the very personification of dukha and all its religious and secular connotations. Like Dreyer’s Joan of Arc, he suffers and he endures with his face. He is no hero: as his later performances show (even in as quirky a movie as Samanala Sandwaniya), the most he can be is a wearied fighter. Which is why, when he was transformed by some of our directors to a king or a warrior, I was disenchanted.

feature is his eyes: half-shut, almost willingly yielding to fate), I thought I’d seen the very personification of dukha and all its religious and secular connotations. Like Dreyer’s Joan of Arc, he suffers and he endures with his face. He is no hero: as his later performances show (even in as quirky a movie as Samanala Sandwaniya), the most he can be is a wearied fighter. Which is why, when he was transformed by some of our directors to a king or a warrior, I was disenchanted.

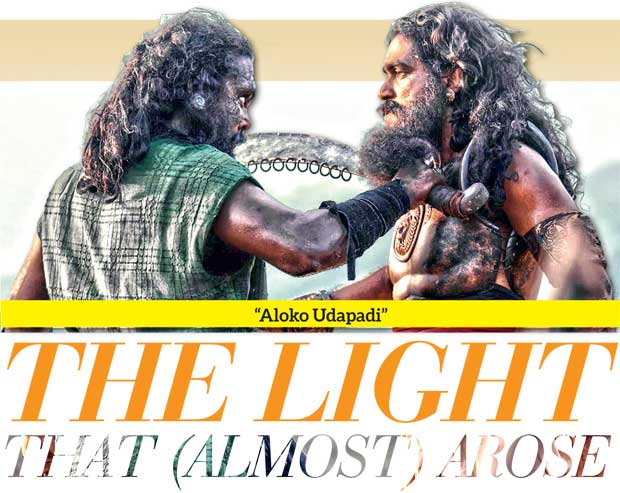

The issue with Aloko Udapadi is that Uddika plays out such a king and warrior. Again. This issue, problematic as it is for me, is compensated for by having him act out a defeated king. When we see him as Valagamba for the first time, therefore, we realise that not only is he a leader who’s soon to be thrown out by enemies from abroad, but also that he is mildly defeatist and needs to assert himself loudly and brashly to compensate for his personal inhibitions.

The reign of Valagamba, with its many splits and rifts, not to mention schisms in the religious order, is second to that of Dutugemunu with respect to cinematic value. Jayantha Chandrasiri went ahead with the latter through Maharaja Gemunu. Now we have the son of an established epic moviemaker, Chathra Weeraman, direct the story of Valagamba, with all those splits and rifts, for what I consider as our film industry’s first real attempt at merging religious boundaries and blockbuster values. That doesn’t make it a superior movie (it’s anything but), but as a writer I am willing to give Chathra the benefit of the doubt. So here goes.

It’s true that Aloko Udapadi is, as one review makes it aptly clear, terribly unsubtle. If one is to lambast the script or handling of the players over that, however, one must go back to the original story, because in Valagamba, more so than even Dutugemunu, we come across a man who belongs by default to the realm of the larger-than-life. Since we know his story, we know how it will end. But since the demerits of the movie in that regard have been sketched out elsewhere, I won’t bother much with them. On the other hand, those demerits stab an otherwise promising epic. That troubles me.

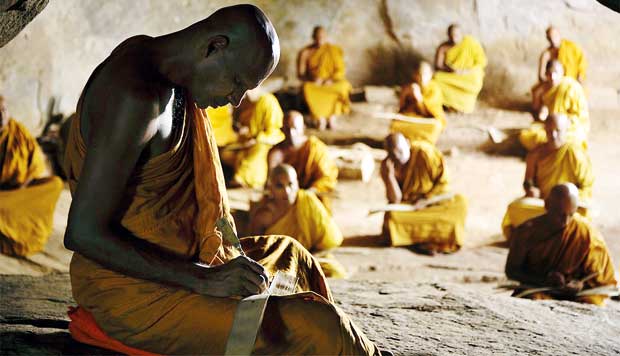

Make no mistake, though, Chathra knows how to compose. His framing, his camerawork, his father’s script (which explains the at times hysterical dialogues and monologues), and his handling of players and locations, all deserve more than a customary clap. Because the plot depends so much on a dignified representation of Buddhism, moreover, he’s resorted to an impressionistic depiction of the Buddhist order: the movie is filled with wide shots of monks reclining in forest monasteries, interspersed with religious chanting highlighting the inevitability of suffering. Visually, then, Aloko Udapadi is a treat.

"To lambast the entire production of Aloko Udapadi as symptomatic of the recent trend in our cinema towards Sinhala Buddhist monoliths, consequently, shows how bankrupt we are"

"To lambast the entire production of Aloko Udapadi as symptomatic of the recent trend in our cinema towards Sinhala Buddhist monoliths, consequently, shows how bankrupt we are"

To a considerable extent, this was supplemented by the acting. I have already pointed at Uddika, who despite his incongruent figure does retain some conviction as a warrior. The rest of the cast, while not exceptionally appealing, nevertheless moved me as much, sometimes even more.

Roshan Ravindra as one of the Five Chola Emperors (Pilayamara), for instance, intrigued me to such an extent that I wished he were more easy-to-categorise. But no, I realised as he hankered after more power by getting the other Emperors to make him their Don Juan and then fell from their favour: Ravindra, unlike Uddika, was not meant to play easy-to-categorise characters. He frowns so hard that he looks as though he’s refusing to reveal his feelings or what he’s planning to do next.

Then there was Dharshan Dharmaraj as Dathika, another of the Five Emperors. Dharshan usually brings to his characters a blend of hot-temperedness and naiveté (think of his performance in Machang), but here he isn’t as complex: in one scene, which might have been an unfortunate afterthought of the director or scriptwriter, he actually twirls his moustache after betraying Pilayamara and revealing that the latter’s courtesan was on his side. It’s as though Dharshan is channelling those villains from South Indian movies, who are endowed with a psychotic face (head down, eyes staring into the camera) and a convenient moustache. Whatever for, I wonder.

That latter point, by the way, sums up my disappointment with the second half of the movie. When the first half was done, I knew that the central conflict in the story – between the prohibition against violence in Buddhism and the necessity of protecting the sasanaya by subverting that precept – would only add more colour and complexity. Imagine my disappointment when, instead of using it to flesh out the plot, that conflict was used instead to depict a rather black-and-white simplification of the campaign to protect the Buddhist order.

Such a simplification, to the best of my limited understanding of our history and of world history in general, does a great disservice to the reality being simplified. We know, for instance, that Valagamba’s story did not end (as it does here) with his order that our oral history be inscribed on Ola leaves (the single biggest accomplishment of his reign, Buddhist scholars will contend): rather, it continued on to the biggest schism in our Buddhist order. He was not a model ruler or for that matter warrior: no less a historical text than the Mahavamsa notes that owing to various personal rifts with his Ministers, he actually left the campaign to regain his throne, thus weakening his army.

The problem with monolithic productions, especially in Sri Lanka and more particularly with respect to the recent spate of historic epics here, is that they’re terribly predictable. Simplifying history, and doing away with all its shades and tones of grey, makes them even more predictable. Even in a technically competent movie like Aloko Udapadi, with its spare but overwhelming use of visual effects, that sense of predictability chops off its greater merits.

Yes, we know Valagamba will return. We know Dathika will be routed. We know that those wide landscapes will be used for the anthima vijayagrahani satana. We know that conniving courtesan to Pilayamara and Dathika will get her just deserts. We know that when Valagamba rises, time will slow down to such an extent that the entire battle will resemble something the Wachowski Brothers could have perfected with some more CGI. We know that Dathika, after fighting with those other Sinhalese warriors, will wade his way through them like he’s in a jungle when he sees Valagamba. And we know that when the battle ends, it will start to rain.

And yet, strangely enough, I am not disappointed. What more can we expect, given our (understandable) fixation with the past? As a friend of mine, Sidath Gajanayaka, told me the other day, South Korea more or less made use of lesser, trivial epics to popularise their country, culture, and movie industry with the Korean Wave. “That was well orchestrated propaganda,” Sidath told me, adding, “We have richer stories, we do nothing with them.” What he implied there was that our epics offer a bigger canvas, fuelling not just the box-office but critical appeal as well. I agree.

To lambast the entire production of Aloko Udapadi as symptomatic of the recent trend in our cinema towards Sinhala Buddhist monoliths, consequently, shows how bankrupt we are. The fact that even Ranjan Ramanayake’s Maya compelled serious critical discussions by our postmodernist pundits shows that our industry no longer subsists on that fine line between populism and artiness.

I am not of course calling Aloko Udapadi populist derogatorily, but I do confess that inasmuch as its technical competence is incongruent with its artistic achievement (or lack thereof), if we keep sidelining that aforementioned spate of epics, we’ll be entertaining the illusion that our cinema should subsist on obscurantism. Thankfully, therefore, Aloko Udapadi does ascertain some value. What that value is will be coloured by our perceptions of our own history, but that’s peripheral to what I’m trying to get at: that Chathra Weeraman’s movie is culturally important. I won’t rate it highly, but I will recommend that you watch it. Right now.

25 Dec 2024 18 minute ago

25 Dec 2024 35 minute ago

25 Dec 2024 49 minute ago

25 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 2 hours ago