18 May 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

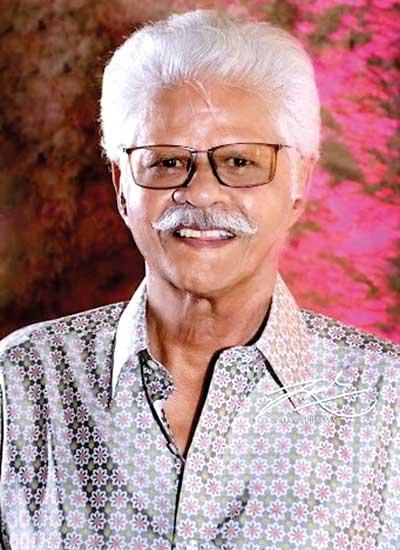

I knew Daya Tennakoon the actor, not so much the broadcaster. I didn’t see any of the plays that put him into the spotlight, including the most famous among them, Kora saha Andaya.

He was, in a very big way, as representative of the era he was born to as Jayalath Manorathna, Mercy Edirisinghe, Vijaya Nandasiri, and Suminda Sirisena were of theirs. Though not quite the last of his kind, he was one of the last. He was certainly the best of the last. By that same token, you could say he was the last of the best too. It works  either way. And yes, it amounts to the same thing.

either way. And yes, it amounts to the same thing.

His acting was, within the confines to which he was tethered for much of his career, extraordinary, yet at the same time fleeting and commonplace. It never really stood out, in other words, though on more than one occasion, within a particular scene or sequence, it almost seemed to yearn to get out, to become more than what it was forced, by the script, to be.

Daya’s face suggested a midpoint, a compromise, between perpetual rebellion and perpetual forlornness: there were moments when it, and the man to which it belonged, protested, argued, dissented, but those moments would almost inevitably be followed by helplessness which distinguished his characters in the films, the serials, and the radio dramas he was in. This quality emerged somewhat distinctly in the latter phase of his career when he moved to television and was obliged to act out a hundred different variations of the same wrinkled, eccentric, helpless, simpleminded, comic character.

"In later interviews, even in the short one he had with me, he was adamant that he didn’t really make the hard yards before entering the film industry; as he memorably put it, “maha loku kattak kawe naha.”

Daya, of course, emerged from a particular social and cultural milieu. He was a scion of a bilingual thespian generation, the generation that bred not only Tony Ranasinghe, Cyril Wickramage, Ravindra Randeniya, and Amarasiri Kalansuriya, but Sugathapala de Silva, Gunasena Galappatti, and Dhamma Jagoda also.

They left school and, if they secured a placement, entered university before 1956 hit; consequently, they were first-hand witnesses to the contradictions that year bred, to how a new generation hailing from a more exclusively Sinhala or Tamil speaking generation—one thinks here of Jayalath, Vijaya, Mercy, and Suminda, all whom were born around the time the likes of Daya and his colleagues-to-be entered school—clashed with those contradictions. Strictly speaking, Daya’s wasn’t a wholly bilingual upbringing—it was, as he described to me once, “mostly Sinhala, with a dash of English from a lesson or two”—but from their very schools, they were exposed to an eclectic mixture of local and foreign art forms which the later Jayalath-Vijaya-Mercy-Suminda generation would learn either at university or while in training under renowned thespians.

He was born Daya Bandara Tennakoon in 1941 in Kandy, Rangala to be exact. Rangala, as he’d recall for me later, was “too far away”, but his father’s job at a tea estate kept him and his family there for a good part of his early childhood. “I grew up in that estate.

The nearest school was the one that the children of estate workers, including the pluckers, went to. That was  where I learnt my letters, and that was where I learnt to appreciate the immense diversity of the society, the culture, we are part and parcel of.”

where I learnt my letters, and that was where I learnt to appreciate the immense diversity of the society, the culture, we are part and parcel of.”

The Tennakoons considered Pilimatalawa as their hometown, to which he returned later. In the meantime, after completing his Grade 5 exam—roughly analogous to the scholarship exam of today—Daya managed to gain entry to Dharmaraja College, “Back then, as it is today, the most sought after public school in the entire province.” Boarded at a hostel, he entered Grade 6, where “I was almost literally hurtled into a different cultural configuration.”

Dharmaraja was caught between two worlds. “We were taught in English and Sinhala, but we did not get much of an ‘arty’ education, if you get what I mean.” There were teachers for music and art, “but the interest in these subjects was never sustained.”

By contrast, “A gurunnanse from nearby was hired as our dancing teacher”, though there too “not much enthusiasm came out.”

As a result of such limitations, “we experimented in the arts in our own free time.” That they were boarded at the hostel helped: every year, they’d get three months off as holidays, and “on the day and night before the vacation started, a prefect called Lionel Weerakoon would get us, hoteliers, to gather and collect some furniture and throw away items, some torn off mattresses and bedsheets, and stage dramas.” This was his first initiation into Western theatre, for Lionel would stage “translations of continental playwrights, including Moliere.”

Both Amarasiri Kalansuriya and Dharmasena Pathiraja had been friends: Amarasiri had studied in the Commerce stream, while Pathiraja, like him, selected Humanities. Daya and “Pathi” entered Peradeniya or the University of Ceylon at the same time, and spent much of the 1960s “frolicking to our hearts’ content along the hills of Hanthana, doing what freewheeling youth did at the time.”

"I knew Daya Tennakoon the actor, not so much the broadcaster. I didn’t see any of the plays that put him into the spotlight, including the most famous among them, Kora saha Andaya"

It was certainly a twilight era, before the more politically turbulent ‘70s, and the two friends made the best use they could of what they had. “We went and saw every movie we could, and we screened them at the campus, most prominently the Czech films.” The Nouvelle Vague was at its peak in Europe, and it was soon to spill over to Sri Lanka, ironically through Pathiraja.

Before it did, Sugathapala Senarath Yapa made Hanthane Kathawa. Daya was, along with several of his campus friends, featured in secondary roles, but as he correctly pointed out, “our contribution went beyond our playing”, since the first draft of Yapa’s script, which centred on varsity life, “was quite deficient in its depiction of relations amongst students and teachers.” Pathiraja, Daya told me, “was adamant on editing the draft.” Which is what eventually happened, and which, if you can see Hanthane Kathawa today, gave it that fresh, exuberant quality that still, after all these years and decades, survives. For Daya, as for Pathi, “it was more than just a baptism of fire.” Unfortunately for them though, “we were pushed into a rat race after university, which meant that all ambitions about acting had to come second.” Finding a job, in other words, was imperative.

In later interviews, even in the short one he had with me, he was adamant that he didn’t really make the hard yards before entering the film industry; as he memorably put it, “maha loku kattak kawe naha.”

Daya and his friends had to find employment, however, and to do that they had to travel to Colombo. “When am kattak kawa,” he chortled. Apparently, he had been good friends with two of his contemporaries, Bandula Vithanage and Tilak Jayaratne, and Bandula helped him stay over in the city while he and his colleague paid visits to one office after another, “always turned away, yet never discouraged.”

Along the way, they befriended several dramatists, including the formidable Dhamma Jagoda as well as Bandula Jayawardhana and Lucian Bulathsinghala. Eventually, they wound up at the Lionel Wendt Arts Centre, founded by Jagoda, where “we were taught all sorts of things, like vocal exercises and memory recall.” Jagoda, of course, was a pioneer of Method Acting, and this got into Daya so much that, as he remembered for me, “I used to think he was more concerned about those exercises than about the actual production!”

This was true, certainly, of his first big break: Kora saha Andaya, Dharmasena Pathiraja’s tribute to Beckettian, Absurdist theatre. Though Absurdism predates Pathiraja – the Sinhala term for Absurdist theatre had been coined by another playwright, Sumana Aloka Bandara – it was in Pathiraja’s hands that it reached its peak in Sri Lanka. “Kora saha Andaya was another experience altogether. The play was basically about two characters, Wimal Kumar da Costa and me, a blind man and a cripple who spend time doing virtually nothing.” The Beckettian undertones (or overtones) impressed the English critic Regi Siriwardena, who’d later trace the contours of Pathiraja’s cinema to this short yet almost universally acclaimed production.

“I may be wrong in considering it a break because I had helped Pathi earlier with Sathuro, the short movie he made for the Film Corporation to kick-start his career. But it made me aware of what acting really entailed.”

From then on, in addition to roles in Pathiraja’s films – including, most memorably, Bambaru Avith, where he’s the wilful servant to Vijaya Kumaratunga’s antihero who’s contemptuously derided by Wimal Kumar da Costa, a Wijeweera-like revolutionary firebrand, as a servile serf – and other films – almost all of which found him as a wizened, sometimes crazy, often eccentric, and always depressed side player – he found a job at the SLBC under Neville Jayaweera’s chairmanship.

“Neville made us feel at home. He wanted fresh faces, university graduates who appreciated the arts and who were not mere competent technicians.

He taught us the mechanics of handling equipment and recording voices.” There isn’t much to talk about, he told me at the end of our chat, and when I disagreed, he admitted that despite all those achievements he listed out, “mine wasn’t what you’d call a complete career, but an unfinished one.” I begged to differ then, and I do so even now.

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago