17 Jun 2019 - 1157

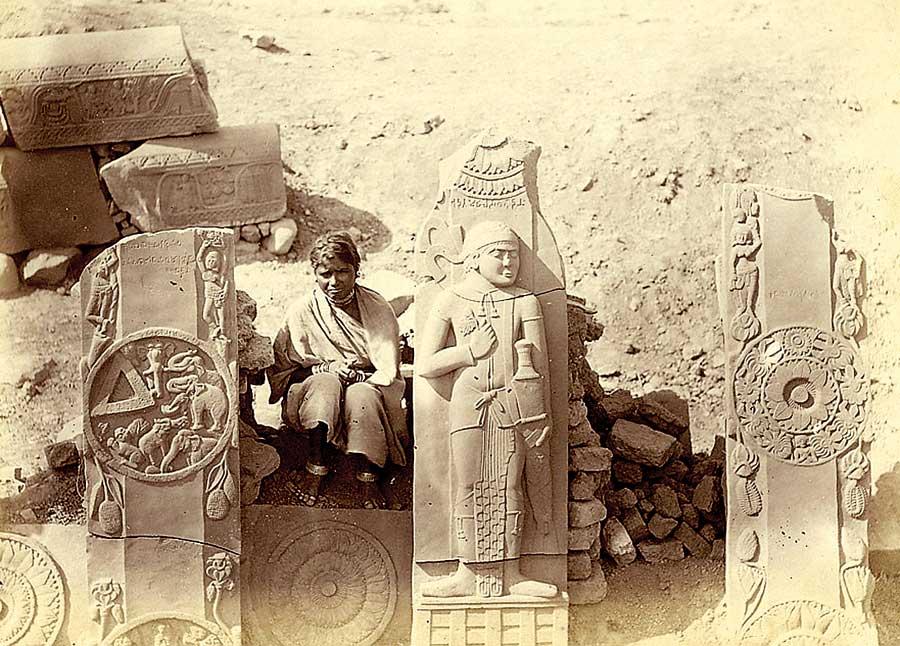

Photograph taken by Beglar in 1874 of village woman with carved railing pillars

The British major had ridden for days from Allahabad while on his way to Nagpur and had arrived in the small village of Bharhut just before sunset. That evening while resting in a villager’s house he noticed some carved stones paving the floor and suspected that they had been taken from some ancient structure. Inquiring about this he learned from his host that  there was a half-buried ruin a little beyond the eastern edge of the village. So in the morning, the major went to have a look at this overgrown mound of bricks and stone. The time was November 1873, the major was Alexander Cunningham and he was about to stumble upon one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made in India and one that is a testimony to the artistic genius of the early Buddhists.

there was a half-buried ruin a little beyond the eastern edge of the village. So in the morning, the major went to have a look at this overgrown mound of bricks and stone. The time was November 1873, the major was Alexander Cunningham and he was about to stumble upon one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made in India and one that is a testimony to the artistic genius of the early Buddhists.

Cunningham was an engineer by training but after arriving in India in 1833 he developed an interest in India’s past which in turn led to an interest, actually a passion, for Buddhism and its history. During his five decades in India, he discovered, verified the location of or excavated Savatthi, Kosambi, Kusinara, Sankassa, Visalia, Nalanda, Taxila, Sanchi and various sites around Rajagaha including the Satapanna Cave where the first Buddhist council had been held. His discoveries did much to demonstrate to Western scholars whose explorations of Buddhism was still in its infancy, that the Buddha was not a legendary or mythic figure but an actual human being rooted in history. Of all the discoveries Cunningham ever made he always considered that at Bharhut to be the most significant.

On examination, the ruins at Bharhut the next morning Cunningham realized that he had found something of great importance, but he had work to do in Nagpur and so after a quick examination of the ruins he continued his way. On his return journey three months later he spent several weeks in Bharhut excavating what turned out to be an extremely ancient and extensively decorated stupa, a veritable gallery of Buddhist art. Under his instructions, J. D. Beglar did further digging at the site a month later and in November the two men returned together to do yet more digging and to search the countryside around Bharhut, discovering carved stones, inscriptions, pillars and statues. For centuries local people had plundered the stupa to use its material for a variety of purposes. Cunningham later wrote that almost every one of the 299 houses in Bharhut village had been built of bricks from the stupa. Because of this more than two-thirds of the magnificent monument had been destroyed.

The stupa had been built between about 100 and 150 BCE during the reign of one of the Sunga kings. It had a circumference of 20.5 meters and was made of brick covered with a layer of plaster. Near the base of the stupa’s dome were small triangular-shaped recesses in which lamps could be placed, much as devotees still do at stupas. A paved path went around the stupa and this, in turn, was surrounded by a stone railing with gates at each of the four cardinal points. The railing pillars and their cross bars are all richly carved, as is the gateway. The carvings are of various geometrical and floral designs, scenes from daily life, sea monsters, lions, lotuses, nagas, and female devas, but most importantly, of Jataka stories and events in the life of the Buddha. Altogether 24 Jatakas are depicted, the name of each story being inscribed above it, and 15 episodes from the Buddha’s life. These are important because it shows that the Jatakas were already well known 150 years BCE as was the Buddha’s biography.

The stupa had been built between about 100 and 150 BCE during the reign of one of the Sunga kings. It had a circumference of 20.5 meters and was made of brick covered with a layer of plaster. Near the base of the stupa’s dome were small triangular-shaped recesses in which lamps could be placed, much as devotees still do at stupas. A paved path went around the stupa and this, in turn, was surrounded by a stone railing with gates at each of the four cardinal points. The railing pillars and their cross bars are all richly carved, as is the gateway. The carvings are of various geometrical and floral designs, scenes from daily life, sea monsters, lions, lotuses, nagas, and female devas, but most importantly, of Jataka stories and events in the life of the Buddha. Altogether 24 Jatakas are depicted, the name of each story being inscribed above it, and 15 episodes from the Buddha’s life. These are important because it shows that the Jatakas were already well known 150 years BCE as was the Buddha’s biography.

One of the most interesting of the other carvings shows a turbaned and bejewelled man riding an elephant and carrying a casket containing Buddha relics. It would seem that there had been a festival at Bharhut, perhaps once a year, when the stupa’s relics were carried in procession, reminding one of the annual Kandy Perahera. One interesting thing about the female figures carved on the railing pillars is that some of them are depicted with tattoos which must have been fashionable at this time. Some of the women have star, moon or flower-shaped tattoos on their cheeks, breasts, and upper arms.

There are also more than a hundred inscriptions on the railings, mostly the names of and brief details about the devotees who donated the parts of the railing or paid artists to do the carvings on them. Interestingly, some of these names are still in use; one monk was named Buddhadasa, one woman was named Chandra, another Srima, and one man was called Nanda. Unfortunately, none of the inscriptions gives the original name of Bharhut or tells us why the stupa was built there or by whom. Perhaps such information was provided but on a part of the monument that no longer exists.

The Bharhut is of interest to today’s Buddhists because many of its features are familiar to us even though we live more than 2000 later. It speaks of the remarkable continuity of Buddhist beliefs and practices. Its depictions of events in the Buddha’s biography and of Jatakas shows the creativity of the early Buddhists in using a range of new mediums (writing and plastic art) to transmit the Buddha’s message. We should take a cue from this and not be reluctant to use today’s new mediums to transmit the Buddha’s Dhamma.

The great stupa was not the only monument at Bharhut. Near it, Cunningham discovered a monastery that had been inhabited until the 10th century, several smaller stupas and a large beautifully decorated temple with a Buddha statue still in it dating from 8th or 9th centuries. Today, nothing remains at the original site other than a low grassy mound. To see the majesty of Bharhut one has to visit the Indian Museum in Kolkata where a whole gallery is dedicated to it and where the surviving railing (vedaka) and its gateway (torana) have been re-assembled. Cunningham wrote a detailed and extensively illustrated book about Bharhut. In it, he acknowledged the help he received from the famous Waskaduwe Sudhuti Thera in helping him identify the Jatakas on the stupa. He apparently had been having a correspondence with some of Ceylon’s scholar monks to help him better understand Buddhism. Since then a dozen or so important monographs have been published about Bharhut and its art.

Nevertheless, despite all the attention given it and the research is done on it mysteries about this wonderful monument remains. Why was it built at Bharhut? We know why the other great stupas of India were built – many where significant events in the Buddha’s career took place. Those at Sanchi and Amaravati were built for other reasons – the first because Asoka had spent time there and Mahinda left for his mission to Sri Lanka from there; the second because it was believed to be where Sumedha made his adithana to become a Buddha. But of Bharhut’s origins, we do not even have legends. The name Bharhut cannot be linked to the name of any location associated with the Buddha. And anyway, as the place is some way beyond the southern edge of the Middle Land, the region we know was the scene of all the Buddha’s activities, it is unlikely he ever went there. Nor is the place mentioned in any later Buddhist literature. Bharhut is situated at the southern end of the Mahiyar Valley formed by fairly high forest-covered hills. The ancient road from Kosambi to Ujjani ran through the valley and was undouble used by merchants and travellers even during the Buddha’s time, being as it were one of the main arteries running to the south, the Deccan, from the Middle Land. Perhaps Bharhut was an important stopping place for travellers and some monks established first a monastery and later a stupa there for the devotional needs of these travellers. Beyond this, we cannot say.

The main temple at Bharhut, now dismantled, photo by Beglar, 1874

23 Jan 2025 34 minute ago

23 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

23 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

23 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

23 Jan 2025 5 hours ago