Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

- The minimum age for marriage under the General and Kandyan laws is 18 years

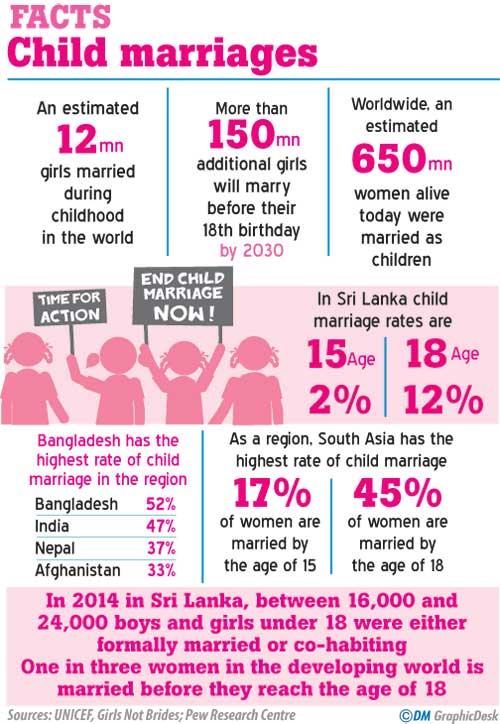

- in 2014 between 16,000 and 24,000 boys and girls under 18 were either formally married or co-habiting

The calls to reform the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) in Sri Lanka have been longstanding. Drawbacks pointed out by the Muslim female activists in the much old  community law are the minimum age of marriage, the lack of mutual consent for marriage and divorce and the serious limitations of the existing Quazi Court system. After the April 21 Easter Sunday attacks, the talks about MMDA reforms came to the table of discussions and women activists are now coming forward and calling for amendments to the decades old community law.

community law are the minimum age of marriage, the lack of mutual consent for marriage and divorce and the serious limitations of the existing Quazi Court system. After the April 21 Easter Sunday attacks, the talks about MMDA reforms came to the table of discussions and women activists are now coming forward and calling for amendments to the decades old community law.

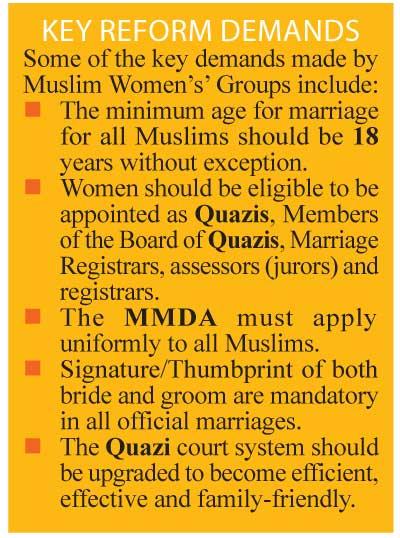

Several female activists belonging to Muslim Women’s’ Groups recently urged the Government to immediately reform the MMDA. The groups highlighted concerns about the potential for reforms to the MMDA being diluted or not passing altogether. Representatives from the groups, including the Muslim Women’s Development Trust (MWDT), the Islamic Women’s Association for Research and Empowerment (IWARE), the Muslim Personal Law Reform Action Group (MPLRAG) and the Women’s Action Network (WAN) spoke at a press conference on July 26 (Friday). Conservative groups such as the All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama (ACJU) have made moves to negate these proposed reforms.

The proposed reforms cover many aspects of life for Muslim women and children including establishing the minimum age of marriage for all Muslims as 18 years without exceptions. Former MP Ferial Ashraff explained the reasons for the proposed reforms, “We are asking for amendments regarding the man-made laws affecting the women of Sri Lanka. It affects both men and women but the discrimination and difficulties are faced by the Muslim women.”

History of the Reform Process

History of the Reform ProcessThe MMDA was drafted by a group of men and passed by a legislature of men in 1951, and the final reform to it was made in 1975. According to a member of MPLRAG, Attorney-at-Law Ermiza Tegal, Muslim women from a range of backgrounds and communities have been pushing for reform to the MMDA for over 30 years. “It’s not a recent idea. This is a historic request from within the Muslim community that this law should be changed.”

Successive Governments appointed at least five different committees, but the State failed to take action. The last committee, appointed in 2009, headed by Justice Saleem Marsoof carried out consultations for 9 years before presenting their findings and recommendations in early 2018. In July 2019, in a salutary move, the Muslim Members of Parliament agreed on14 recommendations towards reform, but once again it appears that there are moves to stymie reform.

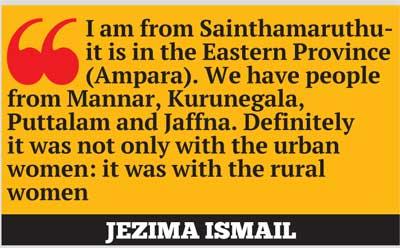

Deshabandu Jezima Ismail, founder of the Muslim Women’s Research and Action Forum (MWRAF), and the President of the Sri Lanka Muslim Women’s Conference (SLMWC), addressed misconceptions about the reform process, “There is an idea that it is the Colombo women-the elite women-who are talking about this. I am from Sainthamaruthu-it is in the Eastern Province (Ampara). We have people from Mannar, Kurunegala, Puttalam and Jaffna. Definitely it was not only with the urban women: it was with the rural women.”

She continued, “Another misconception is that it is only women who are working on it. When we formed the Independent Committee of the Reform of the Personal Law we issued a report. Two noteworthy signatories were the Chairman of the Quazi Board plus an Honorable Justice. We had men in the field; we had intellectuals- we had all these people subscribing to this with us.”

Tegal named discrimination and inequality as some of the main reasons that people are campaigning for reform to the MMDA, “The MMDA is discriminating, not benefiting and it leads to intimidation and violence of Muslim women and girls in particular. It reflects badly on the community in general,” she said. Tegal further emphasised that Muslim women are treated as second-class citizens, “We do not have the freedom to choose, think and govern our own lives.”

A controversial aspect of the MMDA is that it does not specify a minimum age for Muslim marriages. Section 23 of the MMDA states that a child below the age of 12 can be married with the authorization of a Quazi judge. This has led to hundreds of cases of under-18s being married, even during the last decade. For example, between 2011 and 2016, 870 marriages involving 13-18 year olds occurred in the Ampara District alone. The minimum age of marriage for all other Sri Lankan citizens is 18 (as of 1995), without exceptions (as of 2002). Furthermore, since 1995, the Penal Code has raised the minimum age of sexual consent to 16- however excepting married Muslim girls above the age of 12.

Some conservative groups oppose the reformed MMDA stipulating a minimum age of marriage. However, with the ACJU stating that according to the Quran there is, “no restriction for age of marriage.” Rizwi Mufti, ACJU President, has stated that, “Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act is perfect in its present state.” Allegations have also been made in recent days that the ACJU has been hijacking the reform process while also lobbying to implement reforms that they favour.

According to Tegal, interpretations of Islam vary which is why the ACJU’s views differ so drastically with other scholars and organizations, “There are a multitude of interpretations of Islam. The ACJU has one of the interpretations. Other Muslim scholars support reform. There is a diversity of opinions.” Furthermore, a press release issued by the groups who organised the press conference stated that they do not feel that reforming the MMDA would violate Islamic values, “We strongly believe that the Sharia principles which promote justice and equality are in full compliance with human rights and the Constitution of Sri Lanka.”

Tegal stressed that reforms must be implemented swiftly and efficiently, “This is not an exercise to sensationalise or blame anyone. We must ensure the urgency of these reforms going through. We must ensure there is no dilution.”

Safana Begum, Attorney-at-Law, emphasised that, “It is the responsibility of Parliament to amend the MMDA.”

In Sri Lanka there are three conventional legal systems of marriage, called the General marriage law, the Kandyan marriage law and the Muslim marriage law, in operation. The general law that has evolved on Roman, Dutch and English laws, is enforced on the low country Sinhalese, Tamils as well as on ethnic and religious mixed marriages. Kandyan Sinhalese have an option of getting married either under the Kandyan marriage law or the general marriage law. Muslim marriage law is applicable to the Muslims living in the country.

The minimum age for marriage under the General and Kandyan laws is 18 years. However, under the Muslim law, women are entitled to marry after completing 12 years and even women less than 12 years of age could marry with the permission of the Quazi board (courts).

High prevalence of child marriages in Sri Lanka

High prevalence of child marriages in Sri LankaWhen we talk about loopholes of the MMDA, the minimum age for marriage is one of the most important aspects. Although the prevalence of child marriage remains low in Sri Lanka when compared to other South Asian nations, the Committee on the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) in February 2018 highlighted a high prevalence of child marriages in some communities within the country. It isn’t only Muslim girls who become victims of forced child marriage, but also girls belonging to other communities as well. Especially poverty-stricken families often try to give their daughters in marriage. Whilst there remains a gap in data regarding the absolute number of child marriages, it was estimated that in 2014 between 16,000 and 24,000 boys and girls under 18 were either formally married or co-habiting.

UNICEF urged the Government of Sri Lanka to take all necessary steps to eliminate the practice of marriage under the age of 18 years in the country, as clearly recommended by the Committee on the UNCRC. Further, UNICEF said it will continue to encourage the prioritization of girls’ education, especially in communities with high rates of child marriage, as a means of tackling the cultural and traditional norms surrounding this issue.

"She was also a victim of forced child marriage, which is legal for Sri Lankan Muslims. As the media reported, she was 16 years old when was taken to the Nallanthaluwa Kodi Palli Mosque in Munthal, Puttalam and forced to marry Mohamed Imran who was 22 years old"

According to new data from UNICEF, the total number of girls married in childhood is now estimated at 12 million a year. The new figures point to an accumulated global reduction of 25 million fewer marriages than would have been anticipated under global levels 10 years ago. However, to end the practice by 2030 – the target set out in the Sustainable Development Goals – progress must be significantly accelerated. Without further acceleration, more than 150 million additional girls will marry before their 18th birthday by 2030.

Worldwide, an estimated 650 million women alive today were married as children. While South Asia has led the way on reducing child marriage over the last decade, the global burden of child marriage is shifting to sub-Saharan Africa, where rates of progress need to be scaled up dramatically to offset population growth. Of the most recently married child brides, close to 1 in 3 are now in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 1 in 5 a decade ago.

In May 2017, Sri Lankans heard about an unfortunate experience of a victim of a Sri Lankan Muslim child marriage. 18-year-old Thameem Fatheema Sharmila died in May after she was tied to a chair, oil was poured on her and set ablaze by her abusive husband. The husband was accused of burning a 4 months pregnant teenager alive. Sharmila a young 18-year-old  Muslim girl was four months pregnant and lost her baby. She is also the young mother of another seven-month old baby.

Muslim girl was four months pregnant and lost her baby. She is also the young mother of another seven-month old baby.

She was also a victim of forced child marriage, which is legal for Sri Lankan Muslims. As the media reported, she was 16 years old when was taken to the Nallanthaluwa Kodi Palli Mosque in Munthal, Puttalam and forced to marry Mohamed Imran who was 22 years old. Marrying against her will, Sharmila did not know that Imran was already married twice before and she was his third wife.

Shreen Abdul Saroor, founder member of Mannar Women’s Development Federation and Women’s Action Network, speaking to the media those days said; “This happened because of the flawed and inadequate laws in the country specially Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act and Domestic Violence Act, growing religious fundamentalism and structures like mosques and Quazi courts playing with women’s rights and of course negligence of the police”.

Issuing a statement on August 6, Civil Society with signatures of 197 activists, artists and 30 organizations including National Peace Council (NPC), Stop Child Cruelty Trust and Women and Media Collective (WMC) said the failure to reform the MMDA has had a dire impact on the Muslim community, in particular women and children.

Issuing a statement on August 6, Civil Society with signatures of 197 activists, artists and 30 organizations including National Peace Council (NPC), Stop Child Cruelty Trust and Women and Media Collective (WMC) said the failure to reform the MMDA has had a dire impact on the Muslim community, in particular women and children.

Taking examples from countries such as Afghanistan and Malaysia, which have taken measures to amend existing provisions, such as increasing the age of marriage and appointing female Quazis, the Civil Society urged that it is high time that the Government of Sri Lanka protects the rights and freedom of Muslim women and girls who have been suffering for a long time.

“The failure to address these problems places women in a vulnerable position and undercuts their right to equality as guaranteed by the Constitution of Sri Lanka. The Government needs to urgently take action to address the repeated failure of the Sri Lankan State to protect the Muslim women and children. While there are differing views within the Muslim community, including among religious leaders and Islamic scholars, the State’s responsibility to protect all its citizens equally must be upheld. It is essential that the Government acts decisively and forthwith to reform the laws that discriminate women from men. In pushing forward on the demands for reform of the MMDA, the Government and the Parliament will better ensure greater equality and justice for the people of this country,” the statement issued by the Civil Society said.