Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

The ‘Sinhala Only’ legislation of 1956 was immediately turned into a bogey by anti-majority propagandists to frighten off progressive political reforms aimed at redressing the historical injustices perpetrated against the nation by European occupations of the previous 450 years. But the dethronement of English by making Sinhala the only official language ‘in 24 hours’ (as S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike had pledged) was not the renegade step which it was made out to be. An obviously well-informed senior citizen signing as ND, in an opinion piece published in The Island/November 1, recalled that even (Prime Minister) John Kotelawala of the UNP, during electioneering that year, promised to make Sinhala the official language, though it was Bandaranaike who was elected to power and was able to implement the proposal. Making the language of the majority Sinhalese the official language was one of the well meant ‘affirmative actions’ taken to put an end to the oppressive discrimination that, particularly, they were made to endure under the British and even under their native successors who got into their boots on the former’s departure. ND also recollected that it was J.R. Jayawardene who moved in the State Council that Sinhala be made the official language in 1944. In other words, it was a necessary transitional first-step taken towards a fuller realisation of national independence from foreign domination; it was not intended to further disadvantage any section of the broad mass of the Lankan population that had long been oppressed and dispossessed by British colonialism.

The ‘Sinhala Only’ legislation of 1956 was immediately turned into a bogey by anti-majority propagandists to frighten off progressive political reforms aimed at redressing the historical injustices perpetrated against the nation by European occupations of the previous 450 years. But the dethronement of English by making Sinhala the only official language ‘in 24 hours’ (as S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike had pledged) was not the renegade step which it was made out to be. An obviously well-informed senior citizen signing as ND, in an opinion piece published in The Island/November 1, recalled that even (Prime Minister) John Kotelawala of the UNP, during electioneering that year, promised to make Sinhala the official language, though it was Bandaranaike who was elected to power and was able to implement the proposal. Making the language of the majority Sinhalese the official language was one of the well meant ‘affirmative actions’ taken to put an end to the oppressive discrimination that, particularly, they were made to endure under the British and even under their native successors who got into their boots on the former’s departure. ND also recollected that it was J.R. Jayawardene who moved in the State Council that Sinhala be made the official language in 1944. In other words, it was a necessary transitional first-step taken towards a fuller realisation of national independence from foreign domination; it was not intended to further disadvantage any section of the broad mass of the Lankan population that had long been oppressed and dispossessed by British colonialism.

Affirmative action regimes implemented by some progressive governments since 1956 including language policy reforms have generally failed due to non-cooperation from certain opportunistic minority politicians who exploit race or religion to win votes at elections, for whom politics is everything and national interest is nothing. It has often been charged that so-called Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism has done a lot of damage to Sri Lanka. The truth is that the Sinhala Buddhists have always been victims of chauvinists of other brands.

The 1956 ‘Sinhala Only’ slogan has to be understood in terms of the political context that prevailed at that time. The existing political reality then was characterised by the majority of the common people being oppressed by an English-speaking Westernised native ruling elite (a privileged minority) that followed at the heels of the recently departed European colonizers in government. Whereas English was a key to privilege and a badge of prestige for this elite, it was a sword of oppression (kaduwa) for the masses. The ‘Sinhala Only’ policy knocked it off its pedestal.

The Sinhala Only legislation was before long amended in Parliament allowing ‘reasonable use of Tamil.’ This reformative trend continued until Tamil was also made an official language in the early 1980s, and today both languages enjoy the same official language status. However, there are still lapses in the implementation of the official languages policy, which affect both communities. Scarcity of Sinhala and Tamil bilingual proficiency among government servants has been a perennial problem, but this is not an insurmountable obstacle, provided politicians in power make themselves responsible for the implementation of official language policies made into law. Such issues need to be addressed by those elected to power without unnecessarily politicising them.

The 1956 ‘Sinhala Only’ slogan has to be understood in terms of the political context that prevailed at that time

Language policy changes introduced in 1956 and appropriately reformed since have done a lot of good to the common masses of the country, particularly in the education of the young. Although ‘language management’ began to rouse wide popular awareness only after 1956, the subject had already engaged the attention of the patriotic segment of the country’s intelligentsia decades before that date. This was mainly due to rising levels of education among common Sinhala and Tamil speaking masses who had been deliberately denied it in colonial times; at that time a decent education was available only in the English medium for the children of the privileged class, and it prepared them to serve as cogs in the colonial government machinery, in the businesses, and in professions such as law, medicine and engineering. This English medium education was superior to the rudimentary kind of Swabhasha or vernacular (Sinhala and Tamil) medium instruction that catered to the rural poor who far outnumbered the privileged minority.

The instruction provided in English medium schools cost the government many times more than what it spent on vernacular education. This was deliberate government policy. To prevent poor parents from sending their progeny to English medium schools, the authorities introduced a fee levying system. The fee charged was not very high, but it was high enough to be too prohibitive for poor parents to afford. The education minister of the State Council C.W.W. Kannangara succeeded in 1944 in seeing his free education bill through after an intense six-year struggle against severe opposition mounted by the privileged class. Initially, his reforms benefited the minority of children attending English medium schools more than it did rural children, because the former didn’t have to pay for their education any longer. But this was insignificant compared to the immense benefit that the free education policy brought to the rural children studying in the Swabhasha mediums. It was not possible to provide English medium education to all the children at that time, and it is not possible even today for a variety of reasons.

It is sometimes argued that Bandaranaike played the official language card to gain power in 1956. This is wrong. Bandaranaike left the UNP in 1951 on a principled basis to form his own SLFP. He later conceived of the country’s polity as a close-knit society consisting of a Fivefold Great Force or Pancha Maha Balavegaya spelt out as Sangha-Veda-Guru-Govi-Kamkaru or Buddhist Monks-Native Physicians-Teachers-Peasant Farmers and Workers. This was seen as an authentic analysis of the prevalent socio-political reality of the time. It seems that the small Westernised ruling elite represented by the UNP was excluded from this formula. Thus dawned the ‘Era of the Common Man’ -- as Bandaranaike often described it. It is nonsense to say Bandaranaike did away with English as the medium of instruction in all educational institutions, as someone said recently.

The minority of schools that had English medium education continued to function as before while Swabhasha education greatly expanded. Kannangara reforms started the ‘Central School System’ in order to extend English medium education to the villages, where well-performing rural students were selected at a competitive examination to study in the English medium from Class Six onwards. However, since it was held that children learn best in their mother tongue, the pioneers of free education decided to phase out the English medium from government schools completely by 1960. And this is what happened.

Although the limited English medium instruction in the government school system thus came to an end, the importance of English for a proper education was never lost sight of. All post-independence governments, particularly, those after 1956, paid the highest attention to the teaching of English as a second language. But the effort became a failure for various reasons, which I don’t want to elaborate on here. It is not true that nationalist politics led to an abandonment of English. The truth is that English was made available to children from all classes irrespective of their economic or social background only after free education was introduced. This was done in compliance with the advice of the farseeing political and civil nationalist leaders of the past century who unerringly recognised English as the indispensable key to modernisation.

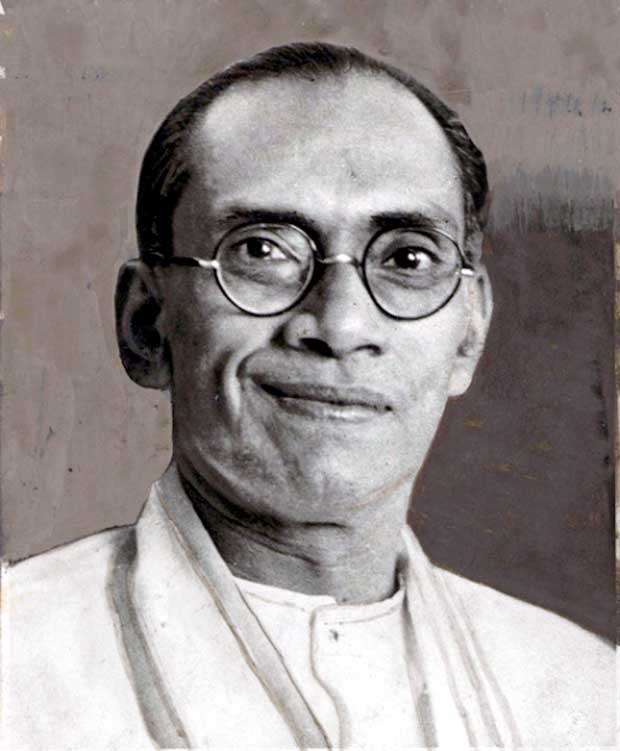

All nationalist intellectuals of the time emphasised the importance of English for a decent education. Even Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933), who used to be condemned, until recently, for his alleged racism, chauvinism, fanaticism, etc., (though he was not guilty of any of these) stressed the need to learn English, in addition the mother tongue; he also wanted young people to learn science and technology, for these were indispensable for creating a modern independent progressive society. He was not averse to the adoption of good social etiquette from the Westernised class. For instance, he wrote articles in Sinhala explaining, for those who liked to use forks and spoons during meals, how to do so in the proper manner. Anagarika Dharmapala was a passionate anti-imperialist, and he made no secret of this, either in his words or in his deeds. But he was careful to ensure that his criticism of the government was within the law. Anagarika was primarily a Buddhist missionary and secondarily a fervently nationalist social reformer. In both roles, he was a prodigious writer and speaker. According to the late Ananda Guruge, who researched into the Anagarika’s life and work for over fifty years, the bulk of his writings and speeches (75%) was done in English. All the pioneering nationalists who worked for freedom from foreign rule were English educated, and acknowledged the value of the language for the betterment of the future of the Sri Lankan people.

The language policy changes that began with Sinhala Only were meant to eliminate English language based discrimination that prevailed even after independence was achieved in 1948. Sinhala is our birthright. It is an inalienable legacy of profound importance for us. Sinhala is a most ancient language. Even Mahinda Thera who formally introduced Buddhism to Sri Lanka more than two thousand three hundred years ago preached in the language of the islanders, Sihala/Sinhale. While preserving that invaluable linguistic heritage, we need to learn English with the same dedication that we learn Sinhala for our survival as a modern nation. There has never been a question about this need over the past one hundred and fifty years, though colonial discrimination against the dispossessed majority of the population prevented its fulfilment over most of that period. However, English language learning in combination with ICT and even English medium education received a new impetus in the last fifteen years. This trend must be fostered and properly channelled in the broad national interest, while preserving our own proud linguistic heritage.