Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

A terrorist’s death won’t end terrorism. Killing a terrorist is no major military feat, but to kill his terror ideology requires much more effort and concerted global action aimed at addressing the socio-economic and political factors that make one a terrorist.

The death of Islamic State (ISIS) leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in last Saturday’s US military raid is good news. The United States President Donald Trump proclaimed that the world is a safer place now. “He died like a dog,” Trump said. Can someone tell Trump that a dog is incomparably better than a ruthless terrorist the US knowingly or unknowingly contributed to create?

Baghdadi and his followers represented brutality. They beheaded captives, raped women, treated them as sex slaves and killed civilians.

Their Islamic state was far from the community that Prophet Muhammad left behind. The prophet’s state was an example of co-existence, as the Madina charter holds out. The prophet disliked war and permitted it only as a means of defence and he laid down rules aimed at protecting non-combatants, the elderly, women, children, religious leaders, religious places of other faiths, trees, crops and animals.

But Baghdadi’s Islamic state was a land of terror, where even a Muslim is declared a non-Muslim and killed. The prophet showed mercy to the captives. His companions took the bones and gave the meat to the captives. The Quran insists that feeding the captive is part of the faith. But the ISIS burnt alive the captives or beheaded them. The ISIS turned Islam upside down and instead of peace, love, charity, justice, tolerance and other universal values the prophet upheld, the ISIS reveled in bloodshed and exhorted its followers worldwide to spread hatred and carnage. The ISIS was a satanic cult. In Sri Lanka, the cult’s followers unleashed their terror on Easter Sunday this year, killing more than 270 people and wounding more than 400. Most of the victims were Christians, whom the Quran respectfully refers to as the people of the book.

The ISIS did not arise out of nothing. It was created.

Just go back in time to see what happened in Iraq after the US invasion of that country in 2003. Sectarian violence and radicalization were not part of Iraqi life before the US invasion. Sectarian violence was a deliberate work of the occupation forces, as confirmed by the September 2005 arrest of two undercover British agents who, clad in Arab clothes, carried detonators in their vehicle.

Soon after Iraq was brought under US control, Washington did not hide its regime change plans for at least two other hostile Arab nations – Libya and Syria. Following the Arab Spring in 2011, the West did not waste the opportunity that came its way to engineer a civil war in Libya and overthrow Libya’s strongman, Muammar Gaddafi.

Hot on the heels of their success in Libya, the West and its Arab allies soon tried to implement the same regime change formula in Syria, but they found in President Bashar al-Assad a tough adversary. The West and its Arab allies soon realized that the Syrian rebels they were arming and backing were no match to Assad’s forces. So they were looking for a formidable rebel force with an attractive jihadi ideology. The ISIS fit the bill.

It all began with the radicalization of the Iraqi Sunnis. The occupation forces provoked the Iraqi Sunnis to become radical with sectarian violence, indiscriminate civilian deaths and the ill treatment of detainees as seen in the deplorable nude pictures taken at the Abu Ghraib prison.

The Sunni anger reached a critical mass and it was exploited first by the Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) led by Abu Musab al Zarqawi and later by Baghdadi.

Baghdadi was arrested in 2004 for a civilian offence and brought to a high security prison known as Camp Bucca where hardline Sunni fighters had been detained. Many Iraqis ask why he was not sent to a civilian prison. Baghdadi befriended hardcore detainees under the watchful eyes of US guards at the detention facility. He played football with the detainees and conducted Friday prayers, for he had a PhD in Islamic studies. He served a sentence of less than a year. Upon his release, he joined the AQI which was without a proper leader after Zarqawi was killed in a US raid. He moved up the ranks and became its leader in 2010. His popularity rose when he staged two jailbreaks and freed hundreds of hardcore detainees in 2011. Baghdadi transported them to Syria where he had already established some presence. The ISIS’ spectacular military successes prompted thousands of moderate Syrian rebels trained and armed by the US and its Arab allies to defect to the terror group. Soon nearly a third of Syria was under ISIS control. Meanwhile, in Iraq, thousands of jobless soldiers of Saddam Hussein’s Army joined ISIS, which had by now become rich enough to pay lucrative salaries to its members with money coming from the Gulf countries.

With its ranks swelling, the ISIS regrouped in Syria and launched a surprise attack on Iraq. As the ISIS moved all the way from the Syrian border to the Iraqi city of Mosul and beyond, the Iraqi troops fled, leaving behind their US supplied tanks and weapons. With large areas in Iraq and Syria under its control, ISIS declared its caliphate in June 2014. From the pulpit of a Mosul mosque, Baghdadi declared he was the caliph of the new Islamic state and urged the Muslims worldwide to join him.

This was probably the moment the handlers decided the time had come to part ways, for Baghdadi’s mission was to conquer Syria – not to set up a caliphate in Iraq.

The caliphate was short-lived, but lasted long enough for ISIS to become rich with oil smuggling and money looted from Iraqi banks and to support a worldwide terror network. In 2017, Iraqi forces backed by the US military trounced the ISIS, while in Syria, the involvement of the Russian military, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and the Lebanese Hezbollah militia tilted the scales of the war in favour of Assad. After the defeat in Baghouz, its final stronghold in Syria, in March this year, the ISIS became a spent force. With Syria now firmly in the hands of Assad, the West felt that Baghdadi was more useful dead than alive. His death gave President Trump respite to emerge stronger in view of the impeachment inquiry in the US Congress.

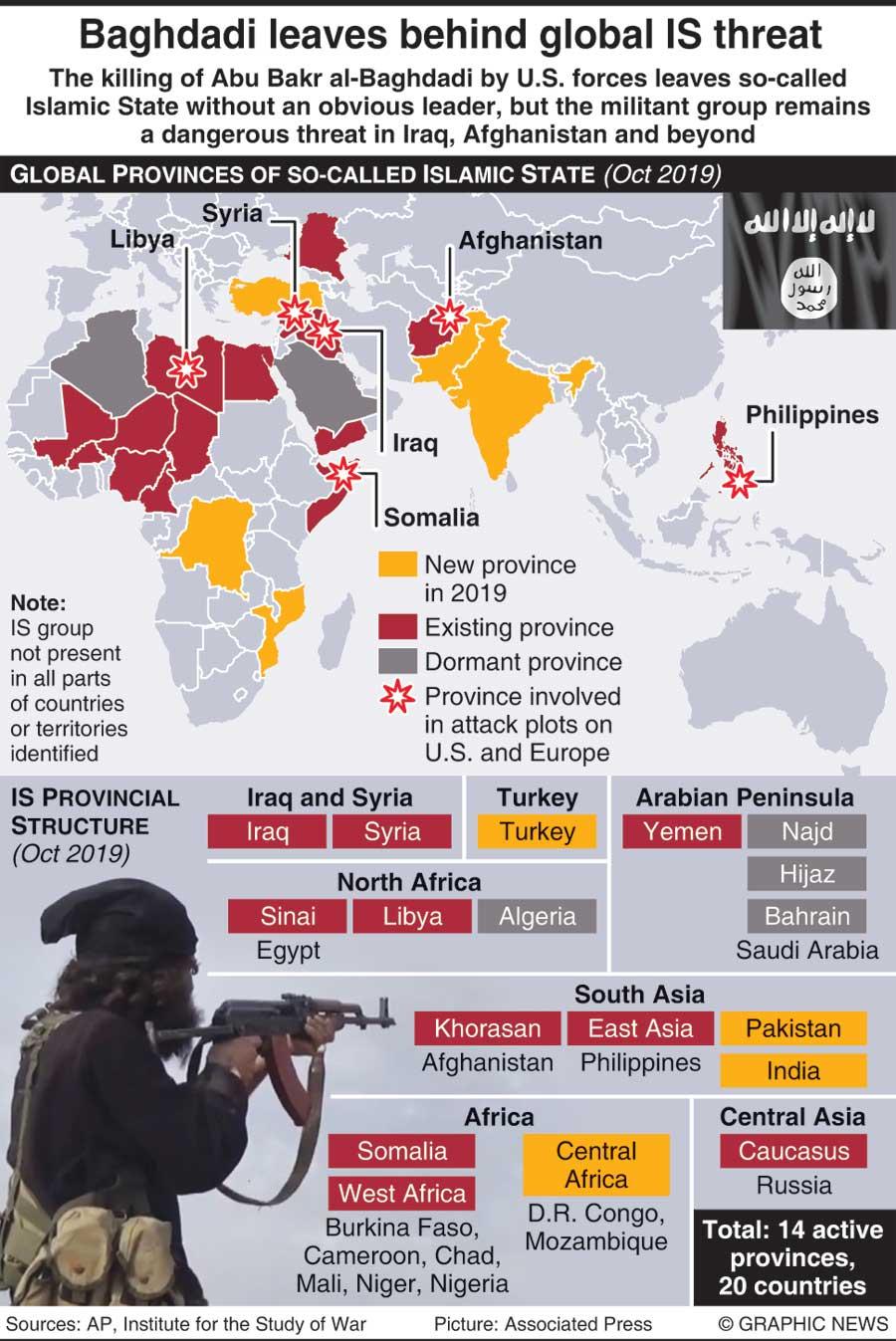

But fighting terror is far more important a matter than politicians seeking self-glory in the death of a terror leader. The global war on terror should not be politicized. Already Trump’s decision to abandon the Syrian Kurds, his erstwhile allies in the war against ISIS, could lead to the launch of ISIS 2.0 under a new leader. The bad news is some 10,000 ISIS prisoners may gain freedom, with Kurdish militia who were keeping a watch over them being forced to withdraw for Turkey to set up a buffer zone after the US military withdrawal from Syria. More bad news: The ISIS has a presence in a dozen countries in the Middle East, Asia and Africa and sleeper cells in Europe and other places. So it’s not over yet.