Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

I asked a friend and a former dance partner of mine, if her children are as passionate about dance as she was. Her response made me think of how confident, bold and utterly fearless we were in our younger days. It also reminded me of how lacklustre and boring children’s school concerts are in the so-called developed countries that we live in now. The talent displayed at school concerts both in the UK and France fall far short when compared to those back in our country. Yet, it is these countries that produce the fantastic dancers that we aspire to be like and hope to emulate. How come?

I asked a friend and a former dance partner of mine, if her children are as passionate about dance as she was. Her response made me think of how confident, bold and utterly fearless we were in our younger days. It also reminded me of how lacklustre and boring children’s school concerts are in the so-called developed countries that we live in now. The talent displayed at school concerts both in the UK and France fall far short when compared to those back in our country. Yet, it is these countries that produce the fantastic dancers that we aspire to be like and hope to emulate. How come?

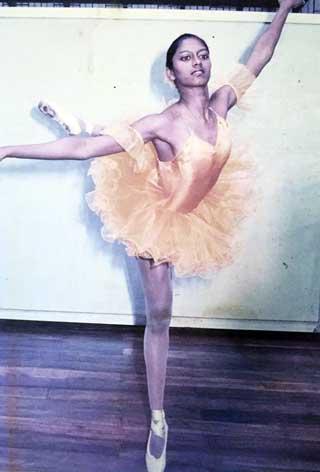

Back in the 70’s and the 80’s we were an audacious bunch of creative youngsters dabbling with our varied cultural interests. I choreographed for such productions as EVITA, Song and Dance and GREASE, when I was in my late teens and early 20’s. I was teaching contemporary dance and presenting my own shows along with Khema and  Naomi until I left Sri Lanka at the age of twenty-seven. Indira Gunesekera returned after training at the Royal Ballet School and produced her first show with the Contemporary Dance Company when she was twenty-one years old. Nadeera Rajapakse made her debut “en pointe” at one of Oosha Garten’s Ballets when she was nine years old. Shannon Raymond presented his first dance concert when he was in his early 20’s. Khulsum Gunesekera returned from the USA after her degree in Dance studies and opening what would have been one of the best dance schools in Colombo had it continued, she was in her 20’s too. And then all that energy seems to fizzle out! We should ask ourselves why.

Naomi until I left Sri Lanka at the age of twenty-seven. Indira Gunesekera returned after training at the Royal Ballet School and produced her first show with the Contemporary Dance Company when she was twenty-one years old. Nadeera Rajapakse made her debut “en pointe” at one of Oosha Garten’s Ballets when she was nine years old. Shannon Raymond presented his first dance concert when he was in his early 20’s. Khulsum Gunesekera returned from the USA after her degree in Dance studies and opening what would have been one of the best dance schools in Colombo had it continued, she was in her 20’s too. And then all that energy seems to fizzle out! We should ask ourselves why.

Is it because most of us left Sri Lanka? Were some of us ensnared by hereditary professions? Was it because there was no national interest in supporting young creative individuals? Was the lack of financial support for dancers the main problem? Was it because of the pressure by some parents who thought that dance was not an ideal career? Did we think that dancing is a short-term career with no prospects of a secure future? Is it because of the obstacles some of us faced when we came back and tried to teach what we had learnt? Did our former teachers make us feel unwelcome? Was it the fear of competition? Or is it that we are daunted by that infamous small island mentality of people who say, “who the hell does he think he is, coming to tell us how to do things right?”

In most other countries, all a child needs to exhibit is a sense of creativity and daring to attract the attention of a teacher or a talent scout. A recommendation paves the way for scholarships which starts the young dancer on a journey. Examiners double up as talent scouts sourcing young talent and luring them towards prestigious schools. Then there are those fantastic  Summer Schools where hawk eyed teachers keep a look out for students with special talents (be it dancing, choreography or dance criticism) with the view of recruiting them. ‘Le petit rat’ of the Paris Opera Ballet school are picked out when they are about eight years old and are given full time dance training as well as a rounded education whilst being boarders in that school. They are assessed frequently to gage if they can cope with the mental stress and rigours of working full-time in a dance company. The best students are eventually invited to join the company. In Taiwan, Japan and China, young dancers are categorised as performers, teachers and choreographers respectively and then sent off to schools all over the world to specialise in these fields. Their contracts stipulate that they must come back and share the knowledge they have acquired.

Summer Schools where hawk eyed teachers keep a look out for students with special talents (be it dancing, choreography or dance criticism) with the view of recruiting them. ‘Le petit rat’ of the Paris Opera Ballet school are picked out when they are about eight years old and are given full time dance training as well as a rounded education whilst being boarders in that school. They are assessed frequently to gage if they can cope with the mental stress and rigours of working full-time in a dance company. The best students are eventually invited to join the company. In Taiwan, Japan and China, young dancers are categorised as performers, teachers and choreographers respectively and then sent off to schools all over the world to specialise in these fields. Their contracts stipulate that they must come back and share the knowledge they have acquired.

A lucrative job back in their country of origin is assured. To this end they are given lessons in English and all their needs for their time abroad as students (meals, transport, accommodation, etc.) is provided by their governments. In the USA there are state competitions that provide a platform for talent to be spotted and nurtured. Those selected through this method are groomed for the international stage by companies and schools alike. Even those from the slums of Cuba can be assured of government support should they wish to pursue a career in dance.

So, what exactly are we missing out on in Sri Lanka?

The obvious solution would be to form a National Dance company through which funding is provided by the government toward aspiring and talented dancers. Unfortunately, seeing the rise in corruption, nationalism and partisanship in our country such a programme will be bereft with problems from the outset.

Our dancers have survived on handouts from generous sponsors. Apart from the obvious necessity for funding which could be sorted out by any school that is willing to extend a scholarship, the missing ingredient for anyone who wants to make a career in dance seems to be encouragement, acceptance and support from those who have been through it all before. There seems to be a palpable hesitancy from both dancers and teachers alike to gracefully bow out and pass on the torch. This is exactly why we will remain stagnant and non-progressive. What does is say about our society when teachers are jealous of the success of their own pupils? What does it matter if a role that was once associated with a great artist is reinterpreted by someone of the younger generation? It is only through the generosity of those who have been there and done it that the younger generation can be encouraged to take up the mantle. Why are there never any masterclasses by teachers of Kandyan dance in our country? Why is it that when an esteemed ballet teacher like Niloufer Pieris had open ballet classes in the 70’s that only one ballet school was generous enough to permit their students to participate? I remember very well that there were numerous teachers who came and watched this series of classes at the DBU, but they did not allow any of their pupils to come. Need I say more?

The western world points us in the right direction yet again. Every time a ballerina steps out to dance the leading role in a ballet such as Giselle or Swan Lake you can be assured that another ballerina who has danced that role previously has meticulously coached her and then let that role be re-interpreted by the dancer who has inherited it. For instance, Alina Cojacaru was coached by Natalia Markova, Rudolf Nureyev singled out Sylvie Gulliem and made her an ‘etoile.’ In every instance, retired stars give budding protégé’s a hand up so that they can become ‘stars’ in their own right.

Talent coexists with inspiration. Without one the other peters out. At a time when advanced technology was not available, we made do by pouring over Princess Tina Ballet books and browsing through the Dance and Dancers magazines at the British Council Library. The USIS, Alliance Francaise and the Geothe Institute would frequently fly down international dance companies whose performances we never missed. These same organisations always invited us to watch films of famous ballets at their premises. Thus, inspiring us and letting us dream. We idolized some dancers whom we knew only by reading about them. For most dancers in Sri Lanka the greatest visible role models were Chitrasena and Vajira.

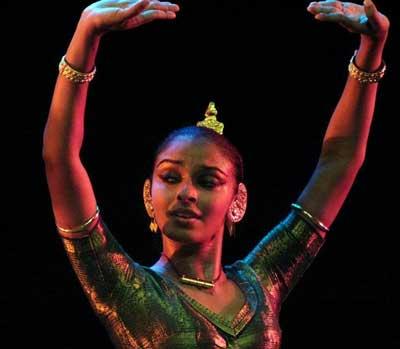

One of my most inspiring memories was the sensational opening night of Chitrasena and Vajira’s ballet, ‘Kinkini Kolama’ at which a 27-year-old Upeka danced the leading role of Upuli, instantly launching her to stardom. Her performance was so utterly breath-taking and flawless that every newspaper that reviewed this show acknowledged her as Sri Lanka’s new prima ballerina stepping up to take the place that was previously her mothers. Supporting her central character were some brilliantly danced cameo roles, among them was one performed by the great Chitrasena himself. This was also the show at which Colombo saw the emerging talents of dancers like Ravibandu and Channa Wijewardene. The costumes, stage sets, music and lighting were perfectly synchronised making it unforgettable. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that this show inspired an entire generation of youngsters who wanted to learn traditional dancing.

Landmark events such as these are a rarity now, even though we have a far stronger and adventurous set of willing and able young dancers in Sri Lanka today. All it needs is foresight, unity, and a sense of fearlessness to revive such productions and pave the way for them to take the stage. Most of the original cast of ‘Kinkini Kolama’ are still very much around and they can easily coach a new cast whilst stepping into the supporting cameo roles themselves. What is there to prevent Ravibandu, Channa and Budhawatte reinterpreting the roles of the three Nilame’s? With them will come their own dance troupes to prop up the numbers needed for a production of this magnitude. Of course, comparisons will be made but the issue we are concerned with is re-interpretation and the re-imagined staging of a classic. And of course, there is no doubt that the supremely talented Thaji is eminently capable of bringing her unique style to the part of Upuli and inspiring the next generation.

Like her, there are many young dancers waiting in the wings. It the duty of the established elders to show them the ropes, pass on the baton and step aside. Let’s bring up the spotlights, turn on the music and let them dance.