Proscription of Muslim groups: Points to ponder

9 April 2021 12:02 am Views - 1608

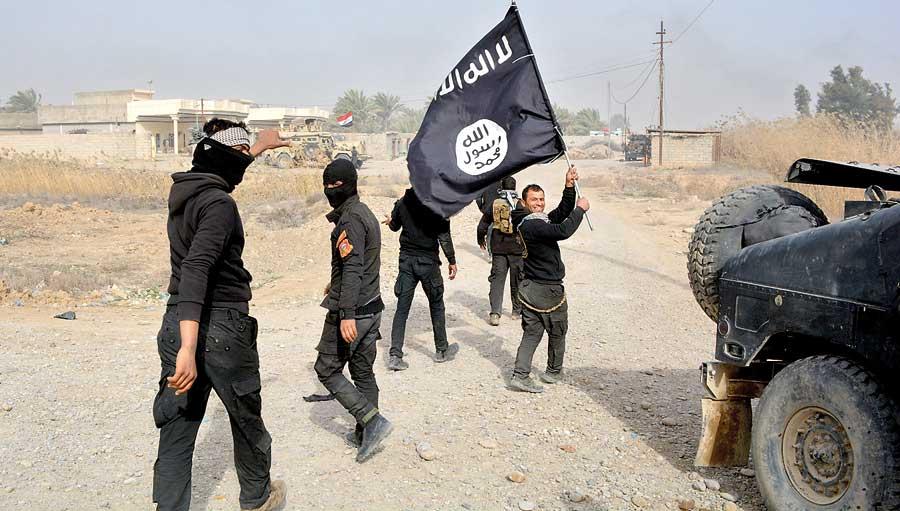

One of the groups to be proscribed is ISIS, which promotes terrorism through its global terror network

The government has obtained the Attorney General’s approval for the proscription of 11 Islamic organisations, some of which carry the Thowheed label associated with Wahhabism, an

The proposed proscription raises, on the one hand, questions about the right to freedom of association, and, on the other, it is seen as a damning indictment on the Islamic leadership in Sri Lanka. It also raises another question: Why only Muslim groups? What about the Bodu Bala Sena, which also came under the strictures of the Presidential Commission that probed the Easter Sunday attacks?

First, the freedom of association is a fundamental right recognized by Sri Lanka’s constitution and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). When proscribing a group, a state is required to follow due process. In other words, the proscription is based on evidence that the group is a threat to peace and national security.

Last month, the government invoked the United Nations Regulation No 1 of 2012 to proscribe several Tamil groups on the basis they promoted separatism. The regulation was adopted in accordance with a United Nations counter-terrorism resolution.

However, the use of counter-terrorism legislation to deny freedom of association has been a concern of human rights activists. They do recognize that states have the responsibility to ensure national security and public safety, yet the concern remains that states can misuse the powers to silence critical or diverse voices. Therefore, they insist that due process is of utmost importance when proscribing a group. A group that is being proscribed must enjoy the right to go before the Supreme Court and challenge the proscription on the basis that the order has violated its right to freedom of association guaranteed by Sri Lanka constitution’s Article 14.

According to the constitution’s Article 157A, a group is deemed to be proscribed only after the Supreme Court, upon an application by any person, declares that the group’s objective is to create a separate state in Sri Lanka.

To ban organisations that have no separatist objectives, Sri Lankan governments have also resorted to emergency. In 2019 in the aftermath of the Easter Sunday bomb attacks, the then president invoked emergency regulations to ban several groups, including the National Thowheed Jamath. In 1983, the Communist Party, the Nava Sama Samaja Party and the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna were proscribed by the then President under emergency regulations.

However, an appeal mechanism to challenge the proscription is a feature of democratic governance. Just as much a government insists it has the right to proscribe a group which it believes to be a threat to national security, a group that comes under proscription should also have the right to a fair hearing in the highest court of the country. In liberal countries, banned groups, including the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), go before courts to challenge their proscriptions.

The 11 organisations in line for proscription are: The United Thowheed Jamath, Ceylon Thowheed Jamath, Sri Lanka Thowheed Jamaath, All Ceylon Thowheed Jamath, Jamiyathul Ansaris Sunnaththul Mohamadiya, Dharul Adhar Jamiul Adhar, Sri Lanka Islamic Student’s Movement, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS/ISIL), Al-Qaeda, Save the Pearls and Super Muslim.

Apart from international terror groups Al-Qaeda and ISIS, which are notorious for their worldwide terror networks, very little is known of the other groups or their involvement in terrorism. At most, what the Easter Sunday Commission heard was allegations that they were promoting Wahhabism. If there is evidence, yes, Sri Lanka’s Muslims will support the government’s move because terrorists such as those who carried out the Easter Sunday attacks have only brought misery and more misery to the Muslims. In fact, the Muslims consider the terrorists as their enemies.

If Wahhabism is equated with terrorism, then Saudi Arabia -- where the Wahhabi strand of Islam is the state religion -- should be regarded as a state promoting terrorism. One may argue that the rest of the world carrying out a campaign against the so-called Islamic terrorism should sever links with Saudi Arabia until it denounces Wahhabism. But this is not happening. On the contrary, states, especially, those in the west, see Saudi Arabia, a G20 member, as a key economic and political partner.

The second question is: why is the government not banning the Bodu Bala Sena? After all, it was among those groups the Easter Sunday probe commission named for proscription. Last month, addressing journalists, Minister G.L. Peiris ruled out the possibility of proscribing the BBS, saying the commission’s recommendation was not acceptable to the government. The selective application of the commission recommendations once again sends a wrong signal to the global human rights community, especially in view of allegations that the government is punishing minorities as seen in its stance of denying the Muslims till last month the right to bury Covid-19 victims.

The third issue arising from the proposed proscription is the failure of Sri Lanka’s Islamic leadership. The stricture is more on the religious leadership than on the political leadership, about which less said, the better. Of late, the All Ceylon Jamiathul Ulama – or the Islamic theologians’ council – has taken upon itself the mantle of leadership, though Thowheed and other groups have questioned the ACJU’s right to represent the Muslims. Thowheed, by the way, refers to the belief in oneness of God.

The ACJU and Thowheed groups regard each other as misguided rivals. The two differ on rules regarding rituals. While the Thowheed groups are strong opponents of innovations in religious rituals, especially visits to the graves of the so-called saints, the ACJU includes moulavis who stubbornly defend some ritualistic innovations and are largely tolerant of the un-Islamic practice of Muslims praying at the gravesites of ‘holy men’. Also with regard to Ramadan night prayers called Tharaweeh, Thowheed groups and the traditional moulavis have conflicting rulings as to the number of prayer units. Often, the two also have clashed on the sighting of the festival moon; there have also been occasions when the two groups have celebrated the Eid on two different days.

However, the feuding groups have missed the wood for the trees. In other words, they are not spending their energy on promoting Islam’s message of worldly and spiritual peace, justice, non-violence, charity and tolerance. That should be the main task.

Muhammad Abduh, a renowned Islamic scholar who lived in the latter part of the 19th century in Egypt, once famously said, “I went to the West and saw Islam, but no Muslims; I got back to the East and saw Muslims, but not Islam.” The point he was trying to drive home is that Muslims could not simply rely on the interpretations of texts provided by medieval clerics like Ibn Taymiyyah and Abdul Wahhab; Muslims need to use reason to keep up with changing times. Abduh said that in Islam, man was not created to be led by a bridle, but that man was given intelligence so that he could be guided by knowledge.

No wonder, sans this progressive vision, in Sri Lanka, Muslim women are being subjected to institutional injustice with the religious leadership opposing key reforms to the oppressive Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act, little realizing that oppression in whatever form is a major sin in Islam.