Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

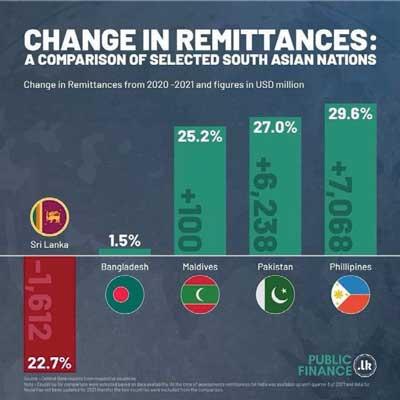

A comparison of remittance inflows to selected South Asian nations between 2020 and 2021 showed Sri Lanka has had the worst record with negative growth in inflows last year, reflecting diverging fortunes between nations based on their foreign exchange policy.

According to data compiled on selected South Asian nations by PublicFinance.lk, a platform for public finance related information run by Verite Research, an independent think tank, Sri Lanka came in as the only nation in the bloc to have recorded a negative growth in remittances in 2021 whereas Bangladesh, Maldives, Pakistan and Philippines had positive growths in the north of 30 percent with one exception.

According to data compiled on selected South Asian nations by PublicFinance.lk, a platform for public finance related information run by Verite Research, an independent think tank, Sri Lanka came in as the only nation in the bloc to have recorded a negative growth in remittances in 2021 whereas Bangladesh, Maldives, Pakistan and Philippines had positive growths in the north of 30 percent with one exception.

The data compilers however said they left out India and Nepal, as they didn’t have current data for fair comparison.

Sri Lanka’s remittances income, the largest foreign exchange earner to the country, fell 22.7 percent to US$ 5,491.5 million in 2021, as the year-on-year decline expanded every month since June last year coinciding with foreign exchange shortages facing the country, creating parallel exchange rates.

The parallel exchange rates available in informal markets offered conversion rates in the north of Rs.240-Rs.250 to a dollar, drawing up a large portion of worker remittances away from the formal channels, depriving crucial foreign exchange to the Central Bank.

An October dictum which mandated both merchandise and services inflows to be converted into rupees also created widespread anxiety among the migrant workers who either held off or sent only the bare minimum back to the country.

Economic analysts point out the fixed exchange rate maintained by the Central Bank as the predominant cause for fall in remittance income.

They say what the migrants do is what any rational economic man would do by sending their earnings via channels like Hawala and Undiyal, which offer up to Rs.40-Rs.50 above what a bank pays for a dollar.

The Central Bank in response decided to offer an extra Rs.10 or Rs.210 for each dollar converted with the additional cost borne by the government and the Central Bank.

The results are yet to be seen in January remittance numbers.

While no country in South Asia has a clean float of their currency, Sri Lanka became an outlier as it lost its reserves during the two years of the pandemic as a result of loss of tourism income and higher foreign loan repayments.

Maldives, whose economy depends largely on tourism, re-opened borders soon after the first wave of the pandemic in 2020 and was able to weather the worst of the crisis unfolded as a result of the pandemic. Its tourism arrivals are now at near pre-pandemic levels.

Pakistan entered the pandemic with an International Monetary Fund programme and the engagement and the assistance deepened with the pandemic, helping its economy. However, Sri Lanka entered the pandemic in 2020 with a weak economic track record, a massive foreign debt overhang and low foreign exchange reserves, which offered less buffer to weather the economic shock unleashed by a black swan event in the form of a pandemic.

A section of economists advocate floating the currency, and raising interest rates to end the foreign exchange crunch plaguing the nation for months now. They are also urging the government to seek an IMF assistance to restructure debt and restore the country’s access to international capital markets. However, the authorities are resisting this option citing extreme economic pain that may be inflicted on people and the massive political cost, which it may not be able to undo, as the government is gearing to go for provincial polls. Further, the Central Bank has repeatedly claimed they have the confidence in the domestically crafted policy fix, which will help Sri Lanka to overcome the prevailing foreign exchange and economic hardships in the next six months.