Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) lead to around 120,000 deaths in Sri Lanka each year, constituting 83 percent of the overall recorded deaths. The revised National Policy and Strategic Framework for the Prevention and Control of NCDs is a positive initiative by the government to address this.

Such policies can play a crucial role in promoting healthier lifestyles, preventing NCDs, and improving overall public health. However, the question that lingers is, how effective are the existing measures, and where can we make improvements?

In the battle against NCDs, the government implemented a crucial policy in 2017 - the Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) tax. This tax aimed to curb the consumption of SSBs closely linked to health problems like obesity, diabetes, and dental issues. While this measure holds great promise, evaluating its effectiveness is difficult owing to data gaps. However, an IPS analysis of how SSB taxes are helping to reduce their consumption in Sri Lanka provides some initial insights.

The case for taxing SSBs

According to WHO 2019 estimates, diabetes is the second highest cause of death in Sri Lanka, accounting for 12,460 deaths. As rates of obesity and diet-related NCDs continue to increase, significant attention has been given to reducing the daily intake of sugar.

Taxing SSBs is a globally recommended option among evidence-based policy options to improve food environments. Research suggests several reasons for taxing SSBs, compared to other food products that contain free sugars. This is primarily due to the observed association between SSBs and NCDs, their high sugar content, and very little nutritional value.

By making these beverages more expensive, governments aim to discourage their consumption, ultimately leading to better public health outcomes. Beyond the health benefits associated with reduced SSB consumption, SSB taxes also raise revenue. When introducing the SSB tax in 2017, the government forecasted Rs. 5 billion in revenue in 2018. Therefore, these taxes are recognised as a sensible way of reducing the incidence of NCDs.

Sri Lanka’s Sugary Drinks Tax

The effectiveness of the SSB tax can be influenced by its structure and rate. Higher tax rates are generally more effective in driving down consumption. In Sri Lanka, the SSB excise tax is imposed as a specific tax – i.e., applied on sugar content per 100 ml. By imposing higher costs on these beverages, the government intends to deter their consumption.

However, there is a factor that often goes unnoticed but can significantly affect the impact of SSB taxes –i.e., inflation. As the general price level of goods and services rises over time, the purchasing power of money decreases. This means that the same tax rate applied today might not have the same “real” value in the future due to the diminishing value of currency caused by inflation. On the other hand, as people’s average income per person goes up over time, specific tax rates have less impact over time.

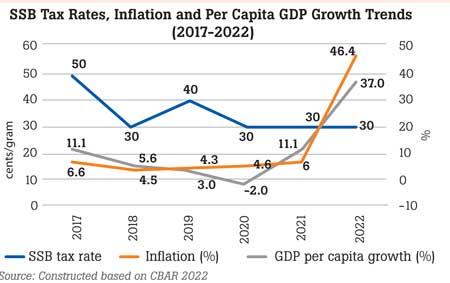

Examining the timeline of SSB tax implementation in Sri Lanka reveals interesting insights. Initially set at 50 cents per gram (c/g) of sugar in 2017, the tax rate has changed, being subsequently reduced to 30 (c/g) per gram (see Figure). This ad-hoc approach to adjusting tax rates has not accounted for inflation, potentially diluting the tax’s intended impact over time.

Is SSB tax effective in Sri Lanka?

Price elasticity of demand measures how responsive consumers are to changes in price. Thus, understanding the price elasticity of SSBs in Sri Lanka can help predict the impact of the tax. In the context of the SSB tax, the IPS study finds that soft and fruit drinks exhibit a high level of price sensitivity, indicating that consumers are more likely to change their consumption behaviour when prices change.

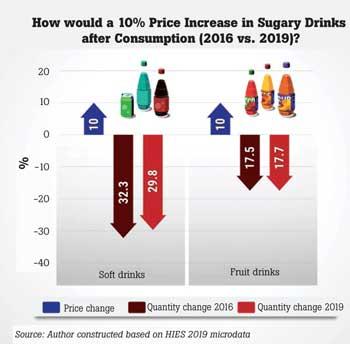

The study reveals that a 10 percent price increase is associated with a remarkable reduction in the quantity of soft drinks (32 percent drop) and fruit drinks (18 percent drop). This finding underscores the tangible impact of the SSB tax on consumption habits, aligning with the initial intent of the tax –i.e., to lower the consumption of these unhealthy beverages.

While the SSB tax’s positive effects are evident, a nuanced trend merits attention. The study highlights that the potential effect of the tax has somewhat diminished over time. For instance, in 2019, people did not respond as strongly to price changes when buying soft drinks compared to 2016 (see Figure).

This implies that when the price of soft drinks increased, it did not affect people’s buying habits as much in 2019 as it did in 2016. This could be due to the prices of other products rising to a higher level or because people’s purchasing power had improved.

Additionally, the price sensitivity of fruit drinks remained relatively stagnant between 2016 and 2019. This intriguing finding indicates that while the tax had a significant initial impact on consumption patterns, this impact might be gradually waning.

The critical factor contributing to this trend is the lack of adjustment of SSB tax rates to account for inflation. Unlike other excise taxes that adapt over time, the SSB tax rates in Sri Lanka have not been regularly updated in response to changing economic conditions. Instead, adjustments have been made on an ad-hoc basis. Sri Lanka’s recent bout of spiraling inflation would have further eroded the ‘real’ tax substantially.

Benefits of effective SSB taxation

The introduction of SSB taxes in Sri Lanka reflects a commitment to tackling the alarming rise of NCDs. However, the real impact of such taxes can be compromised by inflation and insufficient adjustments over time. For these policies to achieve their intended goals, it is imperative to implement tax rates that factor in economic changes and maintain their potency in discouraging SSB consumption.

By adopting a comprehensive and adaptive approach, Sri Lanka can significantly improve public health outcomes and curb the NCD burden.

Policymakers should consider a proactive and data-driven approach to achieve meaningful reductions in SSB consumption through effective SSB taxes. Regular reviews of the tax rate, aligned with inflation and income growth, can help ensure that the tax remains a potent tool for promoting healthier dietary choices and combatting NCDs.

Furthermore, imposing a tax on unhealthy products such as SSBs will support the government’s continuous efforts to generate revenue without increasing the costs of essential goods at a critical time for the economy.

* This article is based on the ongoing IPS study ‘Strengthening Fiscal Policies and Regulations to Promote Healthy Diets in Sri Lanka’. It is funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada.

(Priyanka Jayawardena is a Research Economist with research interests in skills and education, demographics, health, and labour markets. Priyanka has around 15 years of research experience at IPS. She has worked as a consultant to international organisations including World Bank, ADB and UNICEF. She holds a BSc (Hons) specialised in Statistics and an MA in Economics, both from the University of Colombo.

Talk with Priyanka - [email protected])