Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

A transparent and needs-based allocation system is crucial to ensure that provincial and smaller schools benefit from the expertise and resources of national and larger schools within the cluster

Sri Lanka boasts a high literacy rate, a testament to its commitment to education. However, beneath this statistic lies a harsh reality: persistent educational inequalities. This disparity is perpetuated by a complex system that divides schools into national, provincial, and categorised types. While the new education reforms propose clustering of schools to address this issue, it’s crucial to examine both the potential benefits and shortcomings of this approach.

lies a harsh reality: persistent educational inequalities. This disparity is perpetuated by a complex system that divides schools into national, provincial, and categorised types. While the new education reforms propose clustering of schools to address this issue, it’s crucial to examine both the potential benefits and shortcomings of this approach.

National vs. Provincial Schools

The current system categorises schools as national or provincial. National schools, often located in urban areas of the country, receive more government funding and resources, leading to better facilities, qualified teachers, and an alumni network that further strengthens the school resources. This advantage translates into superior academic performance, with national schools consistently dominating university entrance exams.

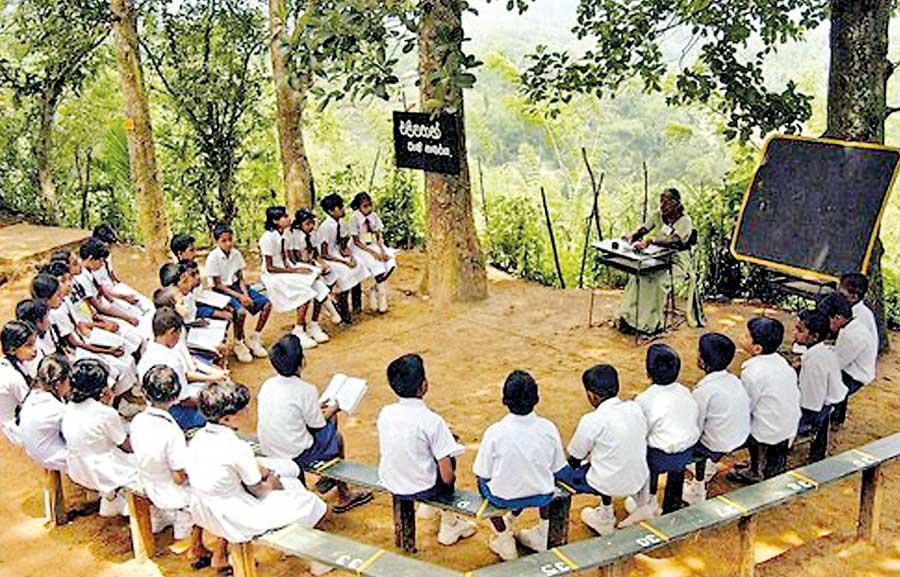

Provincial schools, on the other hand, grapple with limited resources. Many are located in rural areas, making it difficult to attract qualified teachers. Crammed classrooms with too many students or sparsely populated ones lacking even a few – both realities coupled with a shortage of essential learning materials, further disadvantage students. This disparity creates a two-tiered educational system, where a child’s location significantly impacts their educational opportunities.

A study by the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in 2018 found that children from poorer households were, on average, three percentage points more likely to drop out of school, and this effect increased for children aged over 14.

Further fragmentation

The current education system further stratifies education by classifying schools based on years of schooling and subjects offered. Type 1 schools, where students can study up to A-Levels consistently produce high achievers. Type 2 and 3 schools cater to students only until O-Level or lower grades, and tend to, on average, produce poorer performance.

This classification, while seemingly promoting specialisation, reinforces existing hierarchies. Students in lower-ranked schools receive fewer resources and are perceived to have limited potential.

Clustering: A promise with caveats

The National Education Policy Framework (NEPF) 2023-2033 of Sri Lanka, available for download on the Ministry of Education websites, presents a blueprint aimed at transforming the country’s educational landscape. One of the reforms proposed is the clustering of schools which would dismantle these rigid divisions, and label schools as primary, junior secondary and senior secondary.

This approach involves geographically grouping schools across categories to share resources and expertise. Each cluster is proposed to have 8-12 schools with 2,000-5,500 students. Larger or lead schools in a cluster are expected to support smaller schools by sharing training programmes, collaborative learning initiatives, and access to specialised facilities (including lab facilities, sports and recreational facilities, and even IT equipment).

Clustering of schools is also supposed to improve student mobility between schools within a cluster.Ideally, this fosters a more collaborative environment, enabling knowledge and resource sharing to benefit all students while also improving choices for students.

The NEPF also proposed to place all schools under provincial council management which would have reduced the hierarchy in funding. However, thisproposal has encountered resistance from the parliamentary sectoral oversight committee which has recommended retaining national schools.The success of clustering crucially hinges on effective implementation and overcoming potential resistance.

Shortfalls

A key concern is the allocation of resources. Will clustering lead to a dilution of resources previously concentrated in national schools? Experts at a recent roundtable discussion on educational equity in Sri Lanka, co-organized by CEPA and the University of Nottingham on May 16th, 2024, highlighted this concern.

It is important to ensure that simply clustering alone is unlikely to spread limited resources even thinner. A transparent and needs-based allocation system is crucial to ensure that provincial and smaller schools benefit from the expertise and resources of national and larger schools within the cluster.

Implementation issues

Building trust in a shifting landscape: Beyond resource allocation, the roundtable discussion also highlighted challenges related to implementation. Building trust and collaboration between schools with historically different statuses and fostering a sense of collective responsibility will be crucial. Overcoming potential resistance from some schools, particularly national schools accustomed to having more resources, is another hurdle.

Legacy of unfulfilled promises: A more fundamental challenge the trust deficit between the public, educators, and policymakers. Sri Lanka has seen a history of educational reforms that haven’t materialised, fostering a sense of cynicism among the public. This is particularly concerning given the proposed clustering approach, which hinges on a high degree of collaboration and buy-in from all stakeholders.

Restoring faith through transparency and communication: To address this trust deficit, transparent communication and a commitment to long-term planning are essential. Policymakers need to clearly articulate the rationale behind clustering and involve educators in the implementation process. Regular monitoring and evaluation, with clear benchmarks for success, can demonstrate a genuine commitment to improving educational equity.

Beyond Clustering: Addressing the root causes

Clustering offers opportunities, but to truly address educational inequality, a multi-pronged approach is crucial. A critical challenge is the shortage of qualified subject teachers, particularly in rural areas. Despite existing allowances, teachers are reluctant to work in remote locations.

Proposals in the NEPF to setup a university with colleges attached to it focused on teacher education should help train more teachers, but how do we incentivise more people to take up teaching as a profession and retain existing teachers? Research findings from other developing countries indicate that higher pay and a clear career development pathway should attract more individuals into the profession; while targeted incentives, such as higher pay for serving in rural areas coupled withhousing allowances or bonuses, could attract teachers to underserved areas.

Collective effort for educational equity

Sri Lanka’s proposed school clustering in theory is a step towards a more equitable education system. However, its success hinges on addressing resource allocation concerns, fostering genuine collaboration between schools, and ensuring effective implementation as highlighted by experts at the CEPA roundtable. Furthermore, tackling the root causes of inequality, such as disparities in funding and teacher distribution, is crucial.

Ultimately, achieving educational equity requires a collective effort from policymakers, educators, communities, and parents. By dismantling the current hierarchical structures and investing in quality education for all, Sri Lanka can truly unlock the potential of its future generation.

(Dr. Vengadeshvaran Sarma is an Assistant Professor of Industrial Economics and Director of Curriculum at Nottingham University Business School, University of Nottingham, UKand a Research Associate at the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA), Colombo. Kalara Perera is a graduate of the University of Colombo and, currently service as a Junior Researcher at the CEPA)