Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Sri Lanka lost access to credit from international financial markets following the rating downgrade in April 2020. The official view of the government was that Sri Lanka could sustainably finance its external debts, provided tourism returned to normal levels post pandemic.

finance its external debts, provided tourism returned to normal levels post pandemic.

The expectation was that tourism would bring in an additional US $ 4.9 billion in foreign currency inflows as the industry returned to pre-pandemic levels.

This view bolstered the position that Sri Lanka was facing only a short-term foreign currency liquidity problem until the COVID-19-related impact on tourism was overcome. As such, policymakers continued servicing the debt instead of restructuring it. This continued until Sri Lanka ran out of reserves and was forced to suspend debt payments with an announcement to that effect on April 12, 2022.

This insight sets out three mistakes that were made in buying into the optimism that normalising tourism would resolve Sri Lanka’s external debt servicing problems. They are: (1) overestimating tourism inflows, (2) failing to understand the two-way street of tourism and (3) neglecting the current account dynamics.

1. Overestimation of tourism inflows

Sri Lanka estimates its tourism earnings based on an exit survey conducted at the airport (see Box 1). In 2018-2019, 5,033 tourists were surveyed. However, as the sample selection method is not disclosed, whether this is a representative sample of tourists is unknown.

Comparative analysis indicates that there may be serious flaws in the survey design. As shown in Exhibit 1, Sri Lanka’s estimates of tourism spend a day from its survey is extraordinarily high compared to peer countries and even those with higher per capita GDP.

The year 2019 is taken for comparison purposes as 2020 and 2021 were not typical years. These years saw significant shocks (2020 COVID pandemic and the 2021-22 economic crisis), which disrupted normal trends in tourism.

In 2019, Indonesia’s GDP per capita was 7.3 percent more than Sri Lanka’s. Yet, Indonesia estimates spending per tourist per day to be almost 30 percent less. Thailand has a GDP per capita that is more than double that of Sri Lanka. Yet, it estimates spending per tourist per day to be about 10 percent less.

The Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA) reports that from 2012 to 2019, on average, only 11 percent of tourists stayed in five-star hotels in Sri Lanka. This low take up of the higher end accommodation, does not support the estimated spending for a tourist couple being at US $ 362.50 per day.

2. Tourism is a two-way street

Relaxing of COVID regulations and encouraging tourism flows is a two-way street. This increases foreign exchange inflows as well as outflows, as Sri Lankans also travel as tourists to other countries.

Relaxing of COVID regulations and encouraging tourism flows is a two-way street. This increases foreign exchange inflows as well as outflows, as Sri Lankans also travel as tourists to other countries.

For instance, in 2019, India accounted for 19 percent (355,002) of Sri Lanka’s total tourists. However, in the same year, 350,000 Sri Lankans visited India as tourists. As such, while tourists coming from India would have added to foreign currency inflows, this benefit is significantly reversed by outflows on the two-way street of tourism between India and Sri Lanka. In the case of India, net inflows could have even been negative.

Therefore, the key variable should be expected net foreign exchange inflows from the two-way street of tourism, rather than expected one-way inflows from tourism. Focusing exclusively on inflows from tourism (already overestimated) led to misplaced confidence that tourism returning to normal would enable Sri Lanka to fully recover its rapidly deteriorating balance of payments position.

3. Neglect of current account dynamics

The third visible indicator that was neglected was the inadequacy of tourism inflows to cover the balance of payment shortfall, within normal current account dynamics. These dynamics were already evident from past years. In the years that tourism was normal and high and there was a high estimate of foreign exchange inflows from tourism, Sri Lanka’s balance of payment position was maintained only by being able to borrow much of what was repaid in debt. Hence, expecting tourism to compensate for the foreign exchange deficit was overly optimistic.

For example, in 2019, Sri Lanka reported a total cumulative receipt of US $ 4.3 billion from tourism. However, in the same year, Sri Lanka issued ISBs worth US $ 2.5 billion. This shows that even with tourism bringing in high foreign exchange inflows, Sri Lanka still needed to issue bonds to meet its foreign exchange requirements. Therefore, the existing current account dynamics already showed that it was not reasonable to expect that tourism earnings could compensate for the loss of access to financial markets.

Box 1

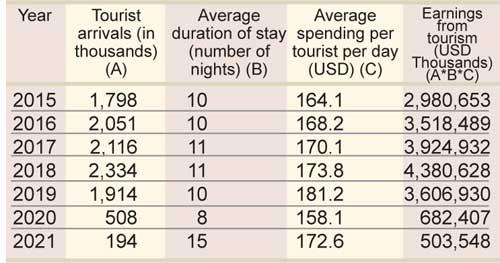

According to the SLTDA, Sri Lanka experienced the highest reported earnings in tourism in the year 2018, at US $ 4.4 billion. This earnings figure is a calculation done using three variables:

1. Number of tourist arrivals counted by the Immigration Department – (in 2019 – 1.91 million)

2. Estimated average duration of stay by a tourist – (in 2019 – 10 days)

3. Estimated foreign exchange receipts per tourist per day – (in 2019 – US $ 181.2 per day)