Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Global social media management platform Hootsuite in its 2021 report on Sri Lanka states that there were 7.90 million social media users in Sri Lanka in January 2021

The number of social media users in Sri Lanka increased by 1.5 million (+23%) between 2020 and 2021

The number of social media users in Sri Lanka was equivalent to 36.8% of the total population in January 2021

There were 30.41 million mobile connections in Sri Lanka in January 2021

The number of mobile connections in Sri Lanka increased by 612 thousand (+2.1%) between January 2020 and January 2021

Participation of citizens and their criticism is a form of freedom of expression which is normal in a democratic country. However, the citizens must be able to exercise their rights – freedom of expression – without fear or unlawful interference. As the newest way of communication, social media is creating an unavoidable impact on societies and political dimensions in countries. Sri Lankans have also witnessed how social media shaped, changed and enhanced the public conversation on certain topics which ultimately transformed political leadership in the country.

Participation of citizens and their criticism is a form of freedom of expression which is normal in a democratic country. However, the citizens must be able to exercise their rights – freedom of expression – without fear or unlawful interference. As the newest way of communication, social media is creating an unavoidable impact on societies and political dimensions in countries. Sri Lankans have also witnessed how social media shaped, changed and enhanced the public conversation on certain topics which ultimately transformed political leadership in the country.

The right to freedom of expression is enshrined in Article 14(1) of the Sri Lankan Constitution, which sets out in broad terms the rights that each of us has. Despite almost every country around the world including Sri Lanka boasts the value of ‘free speech’, governments around the world routinely imprison people for speaking out against the political leadership or policies implemented by them.

Among them was a university student who was arrested and remanded in May, 2019, for publishing a fake rumour on his Facebook account saying that the flight en route to China with former President Maithripala Sirisena on board had crashed. Another university student who allegedly spread a rumour that a special quarantine centre had been built for VIPs, was arrested. In another incident, a woman was arrested under Sri Lanka’s Computer Crimes Act for allegedly spreading a false rumour that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa had contracted the virus.

The case of Ahnaf Jazeem, a young Sri Lankan poet and teacher, who has been detained for over 18 months, also gained much attention as he was bailed out last month by a High Court judge at Puttalam. Ahnaf was in remand under the PTA since May 2020 after he was arrested in connection with a Tamil-language poetry anthology called Navarasam, which he wrote and published in July 2017.

In August 2021, former Spokesperson of the Health Ministry Dr. Jayaruwan Bandara was summoned by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) regarding comments he made in a television interview on the high prices of COVID-19 tests and the general handling of the pandemic. In the same month, social activist Shehan Malaka Gamage was summoned before the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). He had been outspoken over the investigations into the 2019 Easter attacks and had claimed on Facebook that there was a political link behind the attacks and that the government should therefore conduct an inquiry into the matter. He was questioned for five days.

It is a timely requirement for a Communication Decency Law

Human Rights Activist and Former Human Rights Commissioner Prathiba Mahanamahewa speaking to the Daily Mirror said Sri Lanka requires a communication decency law.

“Currently, there is no specific legislation in Sri Lanka when social media users sharing, forwarding, and disseminating defamatory materials and videos on various social media platforms in Sri Lanka. Therefore, it is a timely requirement to introduce the Communication Decency Act like many western countries, where they take legal action according to the provisions of this law for defamatory and illegal contents and video clips,” said Mahanamahewa.

He further explained that freedom of speech and publication is not an absolute fundamental right under the UN convention of 1966 ICCPR and the Declaration of 1948 UDHR as well as 1978 Constitution Article 14 (1). “One of the main limitations is defamation and restrict the free speech. When analysing any defamatory or similar incident under section 120 of the penal code, it may further investigate feeling hurt by criticism or in a conflict of opinion and the motive or purpose of such defamation to create a series of actions for any other provocation and hostility or violence in the society.”

Legislations in place for social media regulation

The current government started emphasising on the importance of regulating social media especially during the COVID-19 lockdown when everyone stayed indoors and the use of social media increased immensely. On April 1, 2020, Police announced that it would arrest those who disseminate false or disparaging statements about government officials combating the spread of the Covid-19 virus. In the days that followed, the government deployed speech-related criminal law with increasing regularity. On April 2, the police announced the arrest of several persons for allegedly spreading disinformation on the Covid-19 virus.

Then in the same month, Cabinet of ministers approved a proposal to draft legislation to combat false and misleading statements on the internet, the cabinet office said, days after the country’s Justice Minister reiterated the government’s commitment to criminalising social media posts deemed fake.

The cabinet approved a resolution tabled by Justice Minister Ali Sabry and then Media Minister Keheliya Rambukwella to advise Sri Lanka’s Legal Draftsman to draft a bill to “protect society from the harm caused by false propaganda on the internet”, a statement from the cabinet office said.

The announcement followed a statement by the Justice Minister that the government will go ahead with a previously announced plan to introduce laws styled after Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), a controversial piece of legislation that has drawn widespread criticism as a tool to control the media and free speech. The minister said that there are posts circulating online that paint the country in an unflattering light, constantly referring to Sri Lanka as an unlivable place.

The cabinet announcement said the spread of false information on the internet poses a serious threat and is seen as being used to divide society, to spread hatred and to weaken democratic institutions.

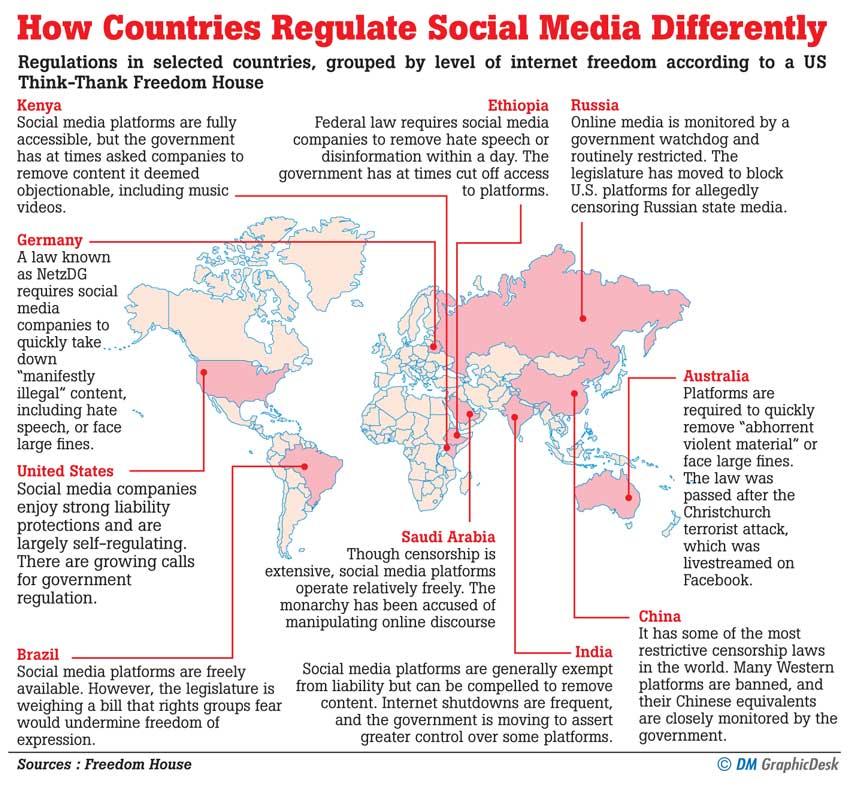

“Various countries have already taken steps to legislate in order to address this problem. Steps should be taken to provide access to accurate information to citizens and civil society by introducing a new law to protect society from the harm caused by false propaganda on the internet,” it said.

However, the Sri Lankan government is under criticism over this bill. Human Rights Council in March last year adopted a new resolution on Sri Lanka, expressing “deep concern” at the “deteriorating situation” in Sri Lanka, and criticised the “surveillance, intimidation and judicial harassment of human rights defenders, journalists and families of the disappeared has not only continued, but has broadened to a wider spectrum of students, academics, medical professionals and religious leaders critical of government policies”.