While no one is immune to contracting COVID-19, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified specific groups that are at higher risks of becoming seriously ill. One such group is those suffering from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including lung and heart disease, diabetes and cancer.

Among the many risk factors for NCDs, unhealthy diets lead the list: research shows that diets high in fat, salt and added sugars contribute more to NCDs than physical inactivity, alcohol and smoking combined.

Population diets are largely influenced by retail food environments that determine what food consumers can access. While the opportunities for influencing food environments are many, they remain largely uninvestigated.

Considerable debate surrounds who is responsible for taking action and what exactly, these actions should involve. The need to resolve such issues has become all the more important, given the unprecedented impacts of COVID-19 on food systems and shopping behaviour, which call for more safe, affordable, sustainable and healthy food environments.

According to government sources, of over 300 COVID-19 victims reported in Sri Lanka as of end-January 2021, only one-fourth died solely due to the disease; 74 percent were suffering from pre-existing NCD-related medical conditions, which were worsened by COVID-19.

Indeed, NCDs – primarily caused by poor eating habits and inactive lifestyles, claim the largest number of Sri Lankan lives, accounting for 83 percent of all deaths, compared to a global average of 71 percent.

This article takes a look at how food environments influence eating habits and highlights the need for examining and regulating Sri Lanka’s food environment to combat the NCD epidemic. Some best practice country examples, which could help inform the policy agenda in Sri Lanka, are also discussed.

Defining and classifying food environments

In simple terms, food environments can be described as the variety of food that is available, affordable, convenient and attractive to people in a given context. It includes food and beverage products in all places where people buy and eat food. These environments differ vastly depending on the context, even within a given country. For instance, supermarkets, cafes and fast-food restaurants are more prevalent in Sri Lanka’s urban settings, while small retail shops, informal street vendors and fresh markets are more common in rural areas.

Distinguishing between ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ food environments is not straightforward. Some can readily be classified as healthy (markets selling fresh fruits and vegetables) or unhealthy (fast-food restaurants that only sell highly processed foods – fresh produce, which is modified through flavours, colours, preservatives or other additives to make them

more attractive).

But most retail food environments lie somewhere between these two extremes, selling a range of healthy and less healthy foods. In Sri Lanka, for example, while fast-food outlets are often branded as being the unhealthiest, many small retail shops also sell unhealthy products such as short-eats and beverages, which are high in fat,

salt or sugar.

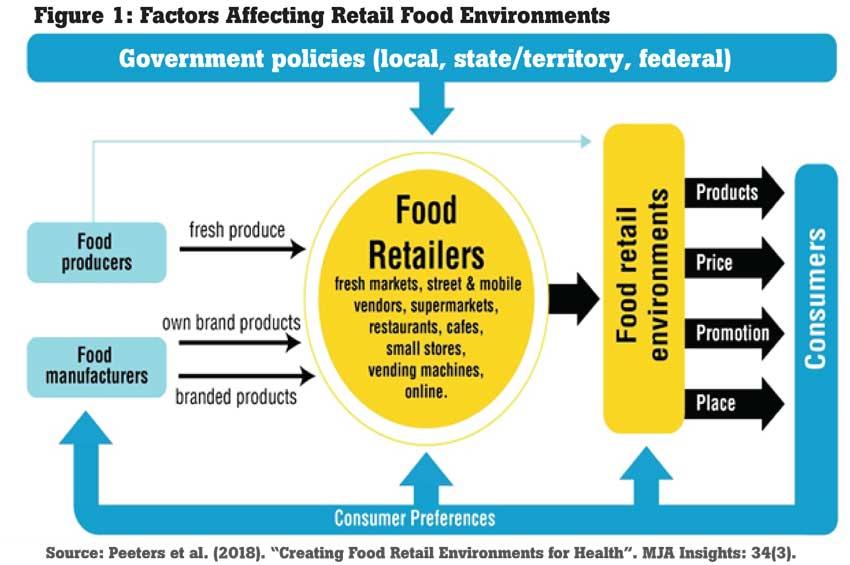

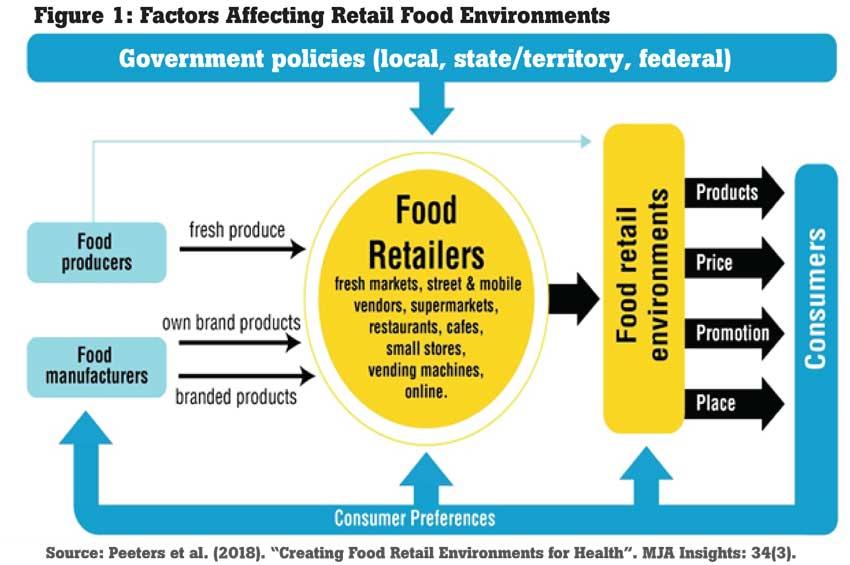

Retailers use many marketing techniques to influence consumer purchasing decisions and increase profitability, commonly classified using the ‘four Ps of marketing’ – Product (availability and variety), Price (affordability), Promotion (advertising) and Place (accessibility). Retailers’ ability to use such strategies, in turn, depends on food systems (food producers and manufacturers) and government policies in place (Figure 1).

Sri Lankan context

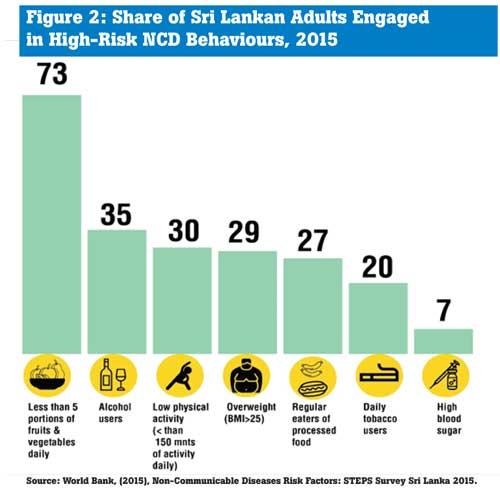

A World Bank survey indicates that the shares of the Sri Lankan adult population engaging in high-risk NCD behaviours are fairly high (Figure 2). In particular, over 70 percent of adults do not consume the WHO-recommended five portions of fruits and vegetables per day, while close to 30 percent eat processed food regularly and are overweight.

While the government has long recognised the need for and has committed to controlling NCDs through multiple policy initiatives, focus on addressing NCD risk factors has gained momentum only recently, apart from interventions for controlling tobacco and alcohol usage.

Recent measures to control sugar and salt consumption include a ‘Traffic Light Labelling System’, which mandates the labelling of the sugar content of sweetened beverages using the traffic light colours and a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) to make them less affordable. Regulating food environments

Policies designed to encourage healthy retail food environments have been successfully adopted only very recently, even at global level. Research at the Global Obesity Centre of Deakin University indicates that there is significant scope for regulatory and fiscal policies from multiple levels of government to positively influence food environments via taxation, marketing and food labelling, as well as urban planning, food procurement and food availability.

Some best practice policy examples at national and state government levels include:

- A ban on the sale and promotion of all foods high in fat, added sugar or sodium within 50 meters from schools in India.

- A ban on the sale of SSBs and highly processed foods to children in several states in Mexico.

- Legislation introduced in the UK to ban over 100,000 unhealthy food price promotions, including limits on ‘buy-one-get-one-free’ deals and the sale of unlimited refills of unhealthy foods.

Local authorities (i.e., municipal or local councils) can introduce local or urban policies that have a direct impact on improving food environments accessible to local communities. In 2020, the city of Berkeley in California became the world’s first to ban unhealthy food at checkouts, also requiring stores over 2,500 square feet to make available healthy food

items instead.

Future steps for Sri Lanka

As discussed, while Sri Lanka has introduced some policies to influence population diets, regulating food environments – particularly the availability, variety and promotion of products – remains an unaddressed area. This is partly due to lack of a comprehensive and technically sound evidence base to inform policy decisions.

Recent research has identified three areas as key targets for influencing retail food environments: (1) mapping, describing and understanding the food retail landscape, (2) working with retailers to test interventions and (3) building evidence for laws and policies related to food environments.

Addressing the second component is particularly important in aiming for retail and health ‘win-win’ strategies in the design and implementation of policies that would be feasible and sustainable in the long run.

For example, highlighting the potential positives from a retailer perspective, such as when switching to a healthier food environment is good for customer perceptions of the store or brand (which is ultimately good for profit), could make the industry more receptive to change.

An ongoing Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) study intends to address these priority areas via a mapping exercise of food outlets in selected urban settings to understand the retail food context and a household survey to examine how food environments influence

household diets.

(Ashani Abayasekara is a Research Economist with research interests in labour economics, economics of education, development economics and microeconometrics. She holds a BA in Economics with First Class Honours from the University of Peradeniya and a Masters in International and Development Economics from the Australian National University. She can be reached via

[email protected])

While no one is immune to contracting COVID-19, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified specific groups that are at higher risks of becoming seriously ill. One such group is those suffering from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including lung and heart disease, diabetes and cancer.

While no one is immune to contracting COVID-19, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified specific groups that are at higher risks of becoming seriously ill. One such group is those suffering from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including lung and heart disease, diabetes and cancer.