Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Nalin Dharshana residence

Some people and certain places take us back in time. They draw out things lodged so long in the back shelves of memory that we’ve almost forgotten they exist. Nalin Dharshana. Nedalagamuwa. A person and a place. In their ‘togetherness’ one can read economy, history, agriculture, entrepreneurship and much more.

Some people and certain places take us back in time. They draw out things lodged so long in the back shelves of memory that we’ve almost forgotten they exist. Nalin Dharshana. Nedalagamuwa. A person and a place. In their ‘togetherness’ one can read economy, history, agriculture, entrepreneurship and much more.

First the place. Nedalagamuwa. That’s coconut country. That’s what kindled memory. Took me back to the fourth grade.

Geography back in the day was very different from what it is now. We had to know the names of the Great Lakes, had to mark on a world map the major mountain ranges, the major rivers, the Equator and the International Date Line and other things largely peripheral to the world of a 9-year old. And it was not just the world map; the map of Sri Lanka also mattered.

In a time without photocopy machines or printed maps in retail shops , we just had tracing paper to copy maps from the text book. On these we had to draw all the rivers, mark the harbors and ancient capitals, draw lines demarcating provinces and of course the Coconut Triangle, that area defined by Colombo, Puttalam and Kurunegala.

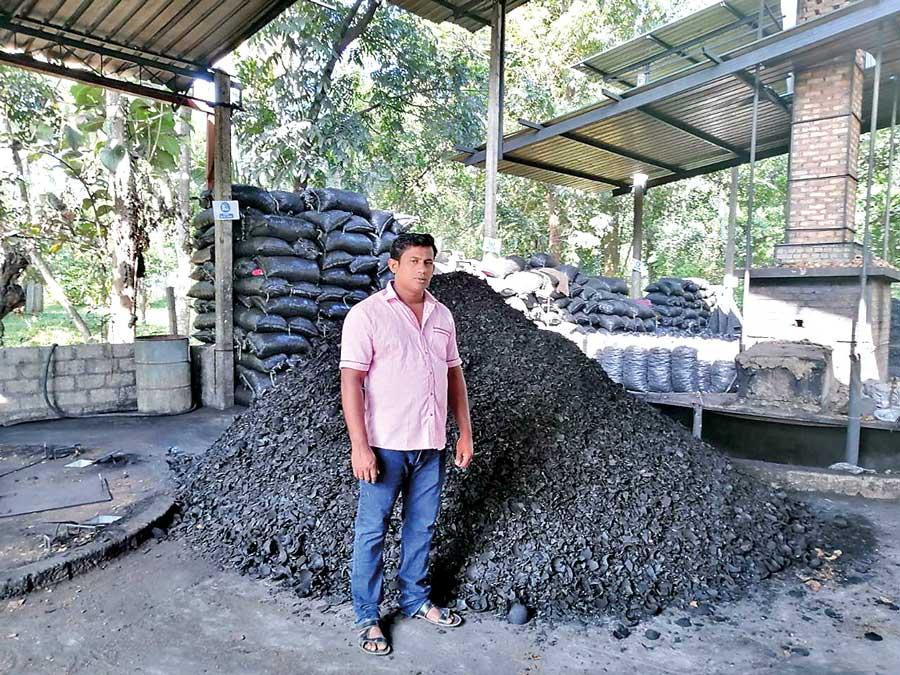

Nalin Dharshana

Two nodes of that triangle were special. I lived in Colombo and spent all holidays in Kurunegala. I would travel within that Coconut Triangle. I was fascinated by the symmetry. The exact distance between trees made for lovely patterns as one drove past coconut estates. Some were well managed and neat. Others clearly were neglected.

Nedalagamuwa is in the coconut triangle, close to Kuliyapitiya. Of course the architectural elements of the landscape have changed over time. The quaint kadamandiya has given way to bustling townships. Thatched houses are now a rare sight. Roads, then rut-strewn and narrow, are not wide and carpeted. The coconut estates are still there, although some have been parceled and sold in ‘land sales’ with names absolutely foreign to Sri Lanka. The same neat lines. Same geometry.

And the man. Malwrachchige Nalin Dharshana, taught me a thing or two about coconuts that I had never imagined as a kid. The son of a farmer and the second in a family of three children, he had attended Rahula Maha Vidyalaya and after the fifth grade had joined the Pannala National School. That’s when things changed. His uncle D.A. Ariyaratne had purchased for him a hand-tractor and had pushed him to purchase and burn coconut shells. I had not known that burning coconut shells into charcoal was quite a widespread business. Now I’ve used coconut shells as fuel when cooking in the traditional dara-lipa. I’ve seen my grandmother use them. I’ve spread kohomba (neem) and maduruthala (thulsi) leaves on smoldering coconut shell coals and my nostrils have twitched at the pungent odor they release. That’s mosquito repellent more ancient than mosquito coils. The point is, it’s hot! Just imagine hundreds…no, thousands…of coconut shells being burnt. The heat. The smoke.

Nalin Dharshana’s old house in the background

The smoke? Why, that’s polluting, right? Wrong. Well, it used to be that way when he was young. He would process 4-5 tonnes of coconut shells every month, selling the charcoal to Haycarb, who was in the business of exporting activated carbon. Purchase-burn-sell, purchase-burn-sell. For almost twenty years.

It was bound to happen. People in the neighborhood started complaining about the pollution. The environmental authorities moved in. The entire coconut shell burning industry almost came to a halt. That snag turned out to be a blessing.

It prompted Haycarb to develop pollution-free technology, appropriately named Haritha Angara. Obviously, working on margins, earning a paltry one rupee per kilogram of coal, people like Nalin Dharshana couldn’t really afford to set up a pollution-free plant, even on a small scale.

Haycarb provided technology and financial assistance. Today, it’s not only a smoke-free operation, but Nalin Dharshana processes up to 150 tonnes a month with the help of six employees. Whereas earlier he had to do the rounds, going around houses in his village and neighboring areas as well, today it’s all delivered to him. The coconut shells are brought from desiccated coconut mills in the area. Zero smoke, zero transport costs. And all cleared by the Central Environmental Authority.

The young boy, pushed into a production process that was utterly foreign, now lives in a plush house, just next to the modest home he grew up in. He is all smiles. And he’s not smiling alone. There are approximately 100 suppliers like him and together they provide coal from around one billion nuts every year. And he’s not alone. Over 100 people in the area have made good thanks to the technological and financial assistance rendered by Haycarb to set up these pollution free firing units.

I’ve seen and been enthralled by the entire coconut-plucking process. The pluckers, the pickers, the rising mountain of coconuts, the counting and the buyer haggling over price was always laced with refreshing kurumba and the customary lunch for everyone involved in the process. Those images and relevant fragrances remain. However, leaving Kulilyapitiya, speeding past coconut estates, I couldn’t help thinking that there’s so much more to ‘coconut’ than meets the eye. Nalin Dharshana gave a glimpse of another universe that existed in the middle of Coconut Land. There are other universes, I am sure.

Haycarb has its own charcoal producing facility which is part of their backward integration process — a centralized and mechanized plant with a 7200 MT/annum capacity.

The gases released during the process, rich in methane, carbon monoxide and hydrogen are combusted in a boiler which in turn runs a steam turbine producing 1 MW of electricity that feeds the national grid.

It was set up in part to ensure the continuity of the activated carbon industry, which by the way brings in US$ 120 million as foreign exchange to Sri Lanka annually. This element of operations was set up by Recogen (Pvt) Ltd., a 100 percent Haycarb subsidiary. One of the key incentives for setting up this plant was to obtain zero air, water and soil pollution and eliminate related health hazards. That’s how they obtained what is paradoxically called Green Carbon.

After the plant came into operation Haycarb became one of the first companies in Sri Lanka to successfully register and trade-in carbon credits by obtaining approval to receive the first block of payment for carbon credits traded under the Kyoto Protocol. The company traded over 4, 000 CER (Certified Emission Reduction) credits under the programme, that was generated during the period 2009-10. The payment was approved after completion of the verification process in April last year.

The credits were awarded to Haycarb’s Recogen plant situated in Badalgama, for environment friendly coconut shell charcoaling process which reduces harmful methane emissions and in turn generate electricity that is supplied to the national grid contributing towards reducing the fossil fuel driven power generation in the country.