Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Growth was marginally lower in 2015 while the current account deficit improved slightly and inflation moderated. Meanwhile, the budget deficit widened and foreign exchange reserves dropped sharply.

The government will have to work to realign fiscal policy toward putting the country on a high and sustainable growth track.

Economic performance

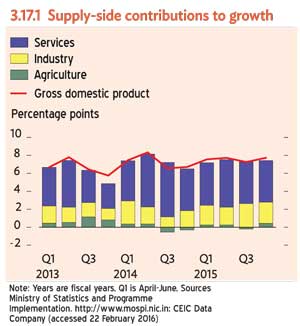

Economic expansion has markedly slowed in the past 3 years from the rapid pace of the post-conflict economic boom. Provisional estimates place growth at 4.8 percent in 2015, marginally lower than 4.9 percent expansion a year earlier (Figure 3.21.1).

Weak global demand and political change characterized the year, as did an expansive fiscal policy following presidential elections in January and parliamentary contests in August that established a coalition cabinet.

Investment faltered as investors decided to wait and see, and as the new administration cut capital spending and temporarily suspended some large investment projects approved by its predecessor. A surge in private and government consumption spending was left to sustain growth during the year.

On the supply side, 5.3 percent expansion in the large service sector was the main driver of growth as the contribution from industry declined. The higher outcome for services came from acceleration in financial activities and in transportation of goods and passengers. Agriculture expanded by 5.5 percent, up from 4.9 percent a year earlier as the paddy harvest recovered and the production of fruit and vegetables increased—and despite lower output of tea and rubber, two major export crops.

Expansion in industry slowed to 3.0 percent from 3.5 percent a year earlier, dragging down growth. Apparel production stagnated on weak external demand, though the important food-processing industry expanded by 5.4 percent even as exports slumped. Weakness in industry mainly reflected a 0.9 percent decline in construction caused by a marked fall in public and private investment.

Preliminary demand-side estimates of real GDP are not available, but nominal expenditure was estimated by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Central Bank projections of private and government consumption expenditure indicate much higher growth in 2015 than in 2014, while investment, exports, and imports fell (Figure 3.21.2). Government consumption accelerated to 25.3 percent growth from 15.9 percent in 2014, reflecting higher pay and allowances for public employees. Expansion in private spending picked up to 8.0 percent from 4.7 percent in 2014 on higher salaries and larger transfers. Fixed capital investment slowed to 2.9 percent as spending on large infrastructure projects slowed and private investors adopted a cautious approach.

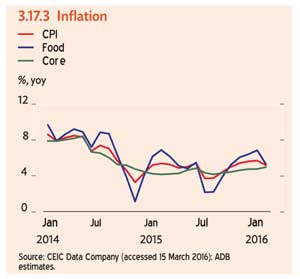

Average annual inflation, as measured by the national consumer price index, moderated to 3.8 percent in 2015 (Box 3.21.1). While food inflation was almost 20 percent in January and February 2015, it subsequently stabilized to bring average annual food inflation to 5.4 percent.

At the same time, nonfood inflation hovered at around 2 percent in the first half of 2015. It trended up in the second half partly because of Sri Lankan rupee depreciation from September but averaged only 2.6 percent for the year. Overall inflation was 4.2 percent year-on-year in December 2015, but in January 2016 prices were 0.7 percent below those a year earlier because of a sharp fall in food prices from December highs and a large base effect (Figure 3.21.3).

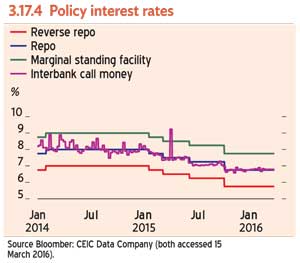

Credit to the private sector accelerated sharply from mid-2014 to reach 25.1 percent in December 2015 (Figure 3.21.4). Much of the growth was from expansion in consumer credit fueled by excess liquidity in the domestic money market. In view of growing pressure on the balance of payments and foreign exchange reserves, the Central Bank tightened its monetary policy and in mid-January 2016 raised the statutory reserve ratio by 1.5 percentage points to 7.5 percent (Figure 3.21.5). As a result, excess liquidity declined to SLRs42 billion from Rs.90 billion in December 2015, causing a slight upward adjustment in market interest rates. In February 2016, the central bank firmed its policy rates by 50 basis points. Growth in credit to the private sector has slowed slightly.

The all share price index remained high at around 7,000 for most of 2015 (despite some overseas investors’ withdrawal of capital) on the expectation that the new government would set private sector oriented economic policy (Figure 3.21.6). However, deepening economic uncertainty and the government’s announcement to suspend tax reforms announced in Budget 2016 caused the market to slump and likely put off new portfolio and foreign direct investment.

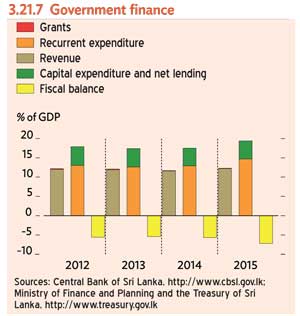

Efforts for fiscal consolidation were reversed in 2015. The new government’s revised budget for 2015 aimed to provide more support for the poor and to collect more revenue from high-income groups and large commercial operations. The budget provided for a sizeable monthly allowance for public employees and higher transfers and subsidies. These changes combined with higher interest payments (which consume about one-third of budget revenue) to boost recurrent expenditure to 14.7 percent of GDP from 12.9 percent the previous year (Figure 3.21.7). Reversing recent trends, revenue increased to 12.2 percent of GDP from 11.6 percent in 2014 on increases in excise and custom duties on vehicle imports as imports surged in response to lower import tax rates set in the revised budget.

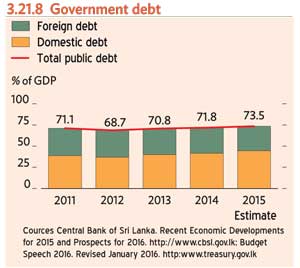

The overall budget deficit excluding grants widened to the equivalent of 7.2 percent of GDP in 2015, well above both the 5.7 percent outcome in the previous year and the 4.9 percent budget target. Total government debt is estimated to have increased to equal 73.5 percent of GDP in 2015 (Figure 3.21.8).

Budget policy for 2016 sought to enhance tax revenue. The 2016 budget, presented to the parliament in November 2015, set a lower minimum threshold for liability under the value-added tax (VAT) to Rs.12 million from Rs.15 million, and revised the prevailing 11 percent single rate into three bands: 0 percent, 8 percent, and 12.5 percent.

The threshold for nation building tax, a levy on gross business receipts, was also revised lower and the tax rate doubled from 2 percent to 4 percent. The budget also aimed to stop ad-hoc and unproductive tax concessions offered by various government agencies. Moreover, tax concessions granted for any investment project were brought under the supervision and monitoring of the Ministry of Finance.

The implementation of major tax reform to the VAT and national building tax were deferred in January 2016. The latest fiscal projection taking into account these developments estimates a more modest increase in revenue equal to 13.2 percent of GDP, rather than 16.3 percent as proposed in the original budget, while the original ambitious public investment target is reduced. In this fiscal framework, recurrent expenditure is to be contained at 14.1 percent of GDP, while public investment will be 5.2 percent. The fiscal deficit excluding grants will narrow to 5.9 percent of GDP in 2016.

The balance of payments was under pressure in 2015 from a decline in exports, weak remittances from workers overseas, and large capital outflows. The current account deficit narrowed, however, on account of much lower spending on oil imports and robust tourist arrivals. Export earnings dropped by 5.6 percent in line with lower earnings from all major export categories as global demand weakened and prices fell. Exports of tea, rubber products, and garments largely accounted for the decline.

Imports also fell during the year, by 2.5 percent, reflecting diverse developments. Imports other than oil—notably vehicles but other consumer goods as well—increased sharply by 10 percent, while oil imports fell by 41 percent because of lower prices, to a total $1.9 billion less than a year earlier.

Earnings from tourism continued to expand robustly, growing by 17.8 percent to $2.9 billion. Overseas workers’ remittances contracted by 0.5 percent to $6.9 billion, which seemed to be partly attributable to the fall in oil prices and weak growth in the Middle East, the main host destination. On balance, the current account recorded an estimated deficit equal to 1.9 percent of GDP in 2015, narrower than the 2.6 percent deficit in 2014 (Figure 3.21.9).

Capital outflow was the major factor in the deterioration of the balance of payments in 2015. Foreign investments in government securities recorded a net outflow of $1.1 billion, while foreign direct investment and portfolio inflows were well below levels a year earlier. The central bank estimates the overall balance of payments deficit to be $1.5 billion, reversing a surplus of $1.7 billion in 2014.

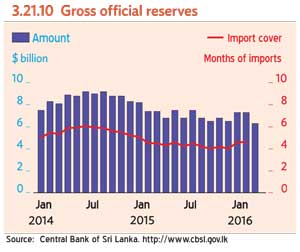

Gross international reserves fell to $7.3 billion in December 2015 from $8.2 billion a year earlier and declined further to $6.3 billion in January 2016 (Figure 3.21.10). Sri Lanka’s latest sovereign bond, for $1.5 billion, was issued on 28 October 2015 at a coupon rate of 6.850 percent per annum. Fitch Ratings rated it BB–, Moody’s Investors Service B1, and Standard and Poor’s B+. Gross international reserves were supported by a $1.1 billion currency swap arrangement with India concluded in September 2015.

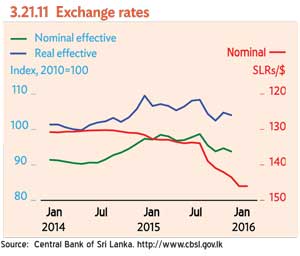

The Sri Lanka rupee was broadly stable against the US dollar for most of 2015 but weakened after September 2015, when the central bank stopped intervening on the foreign exchange market. The rupee depreciated by 6.2 percent from Rs.137 to the dollar at the end of August 2015 to Rs.146 as of 11 February 2016 (Figure 3.21.11). In all of 2015, the rupee depreciated by 9 percent against the dollar and by nearly 4 percent in nominal and real effective terms, following a 3-year trend of gradual appreciation.

External debt in June 2015 was $43.5 billion, equal to 58.1 percent of GDP, of which 83 percent had a maturity of more than 1 year and was categorized as long term. The government’s outstanding external debt amounted to $24.3 billion, or 56 percent of all external debt, of which $8.4 billion was in debt securities (treasury bills and international sovereign bonds) and $6.8 billion was from multilateral lenders, $6.1 billion from bilateral lenders, and $3.0 billion from commercial sources.

Economic prospects

Weak global demand and uncertainty over policy will continue to hold down economic performance in 2016. Weak demand and low prices for Sri Lanka’s major exports will constrain economic growth and exert pressure on the balance of payments, though somewhat lower oil prices projected for 2016 will alleviate this pressure, albeit less than in 2015. Continued concern over fiscal consolidation will hinder foreign investment and other capital inflows. Notably, In February 2016 Fitch Ratings downgraded Sri Lanka to B+ from BB– with a negative outlook because of rising refinancing risk and weaker public finances.

Fiscal consolidation is to be put back on track by a revision of the 2016 budget. Following the suspension in January 2016 of earlier plans for tax reform, the government has been preparing a revised budget for 2016. Its proposed tax reforms include a VAT rate increase to 15 percent from 11 percent and the introduction of a capital gains tax. The revised budget will be the basis for discussions with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for possible support that interests the government. IMF support, once agreed, will protect against expected pressures from external imbalances as it builds international confidence and facilitates fiscal consolidation and tax reform.

A national development strategy will facilitate investment, both domestic and foreign. The Prime Minister outlined the government’s strategy in his statement in November, which focused on job creation, rural development, linking up to global value chains, and attracting more foreign direct investment. The 2016 budget builds on these priorities and introduces some measures necessary to attract foreign investment. The master plan for the Western Region Megapolis Project, released in January 2016, elaborates on the development plan for Western Province, including Colombo, which will be a significant component of capital expenditure over the medium term. The public investment plan for 2016-2018 to be published in May 2016 will prioritize and streamline public projects, provide vision for economic development, and thus promote private sector investment.

Private investment can recover to drive economic growth in 2016, assuming that the revised budget is approved in mid-2016, the national development strategy is finalized, and agreement is reached with the IMF on possible support. Growth will be driven by domestic demand as weak global economic recovery suppresses external demand. Consumption will increase only modestly after strong expansion last year. Public investment has potential to expand once additional revenue streams materialize. Under these circumstances, there is room for private sector investment to lead growth. In this scenario, economic growth is projected to pick up to 5.3 percent in 2016 and further to 5.8 percent in 2017 as the global environment improves.

Inflation will accelerate moderately under monetary tightening. While domestic demand remains restrained, the 9 percent depreciation of the Sri Lanka rupee in 2015 will exert upward pressure on import prices. The fading of base effects from several reductions to administered energy prices in 2015 may also cause some upward movement in inflation in 2016. Monetary policy will maintain a tight stance balanced between restraining price increases and fostering economic recovery. With global oil prices holding down domestic fuel prices, and assuming a steady supply of agriculture products, inflation is expected to rise only moderately. Accordingly, inflation is forecasted to pick up to 4.5 percent in 2016 and, as growth strengthens, to 5.0 percent in 2017.

The balance of payments will continue to be under pressure as exports stay weak during the global slowdown and remittances slacken from workers in the Middle East. Although exports will continue to struggle, a positive factor is the expected renewal in 2016 of concessions under the Generalized System of Preferences Plus scheme of the European Union. Imports will contract as oil prices decline and vehicle imports subside in response to the import tax. Receipts from tourism will continue to grow at a healthy rate in line with recent trends. Given this outlook, the current account deficit is projected to widen slightly to 2.0 percent of GDP in 2016 and improve in 2017 to 1.8 percent as exports pick up.

The government’s commitment to fiscal consolidation is critical to ensure capital inflow. IMF support would help the government to maintain sufficient gross international reserves to sustain public and investor confidence. The overall balance of payments is likely to remain in deficit for the second consecutive year in 2016.

Policy challenge—tax reform

A persistently low revenue ratio has been a major challenge to Sri Lanka’s efforts to achieve fiscal consolidation while meeting growing needs for social expenditure and public investment. The ratio of tax to GDP is, at 12%, uniquely low among countries at a similar stage of development. The tax system is quite complex, with a multiplicity of taxes. A relatively thin base reflects significant base erosion as various government offices granted an array of tax incentives. The government’s repeated attempts to improve the tax system have had little impact. The Prime Minister’s statement to Parliament in November 2015 indicated that he intended to address this issue partly by strengthening tax management and removing tax holidays and benefits. His policy includes minimizing regressive taxes and doubling the ratio of direct to indirect tax contributions from 20/80 to 40/60.

The 2016 budget nevertheless depended on expanded indirect taxes. It planned ambitious tax increases worth 2% of GDP, including increases in the nation building tax (NBT), excise duties, and taxes on external trade, while income taxes both personal and corporate are reduced marginally (Figure 3.21.12). The budget proposed expanding the tax base for the VAT and the NBT by lowering the minimum tax liability threshold and doubling the NBT rate. Indirect taxes in general place a smaller burden on tax administration and they can immediately increase revenue, but they are regressive in that they impose a larger burden on the poor than the rich. Further, since the NBT is levied on turnover, the burden cascades and has a larger distortionary effect on the economy than does a VAT.

Moreover, personal income tax will become less progressive as the rate is unified at 15% from six bands: 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 percent. Corporate tax rates were reformed to two bands—15 percent broadly and 30 percent applicable to a few selected activities including betting and gaming, liquor, tobacco, and banking and financial services—from the previous structure of 12 percent for incomes below Rs.5 million and 28 percent for higher incomes. The annual tax free threshold for the personal income tax was increased to SLRs2.4 million from SLRs750,000, further narrowing the tax base. These proposals run counter to the policy outlined by the Prime Minister.

Proposed tax amendments in March 2016 address progressivity in the tax system. The Prime Minister announced to Parliament details of his proposed tax amendments. The proposal is to change the VAT to a 15 percent single rate that will not be imposed on essential commodities or electricity (though VAT concessions for telecommunications, private education, and private health expenditure will be removed), keep the NBT tax rate at 2 percent, and introduce a capital gains tax. The 2016 budget proposals on personal income tax and corporate tax are to be suspended. The statutory personal income tax rate to be applied from 2017 is increased from 15.0 percent to 17.5 percent.

The government has taken well-considered steps to enhance revenue. Further improving the tax system requires stronger policy analysis and more capacity in decision-making agencies. The Inland Revenue Department needs to set up a comprehensive tax policy analysis unit with the capacity to conduct statistical modelling and social surveys. Such analysis will inform policy makers on the impact of tax policy changes on revenue and the economy and facilitate tax administration policy analysis, intervention, and equitable revenue generation.