Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

In a move that heralds greater bilateral cooperation, Chinese Defence Minister Lieutenant General Wei Fenghe paid his first visit to India in

In a move that heralds greater bilateral cooperation, Chinese Defence Minister Lieutenant General Wei Fenghe paid his first visit to India in

August 2018.

The visit was precisely a year after both sides decided to withdraw their forces following the two-month standoff at the Doklam trijunction. The details from the defence ministers’ meeting point towards an adherence to greater confidence building measures to avoid Doklam-like situations from resurfacing.

While no formal agreement was signed, the two sides agreed to reduce troop confrontations, increase border personnel meeting points and operationalise a hotline between senior military officials. A revamp of the 2006 memorandum of understanding on defence cooperation was high on the agenda.

Similar understandings have been reiterated for over two decades after the Peace and Tranquillity agreement was signed in 1993. But the present development should be seen as part of several ongoing transitions that aim to take the post-Wuhan consensus beyond just managing border disputes. Although India seems to be attempting a regional balancing strategy that is within the contours of the Wuhan spirit, China seems to be hedging to avoid any pressure build-up in the Indo-Pacific.

General Wei’s visit assumes greater significance as it closely coincided with Japanese Defence Minister Itsunori Onodera’s visit to New Delhi for the India–Japan Annual Defence Ministerial Dialogue. According to the resulting joint statement, Onodera and Indian Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman ‘had a frank exchange of views on the current security situation in the Indo-Pacific region, including developments in the Korean Peninsula’ and expressed interest in ‘expanding cooperation in the maritime security domain’.

Key focal point

Since the Indo-Pacific region is consistently the key focal point of India–Japan talks, the decision to hold talks with General Wei at such a time was interpreted by the Indian media as New Delhi’s subtle signalling that its stance on the Indo-Pacific was not exclusionary of or threatening to China. Before the Wuhan consensus, every Chinese intrusion into the Indian territory was immediately followed by blame-games and widespread media coverage. Such developments are now subdued, if not completely absent.

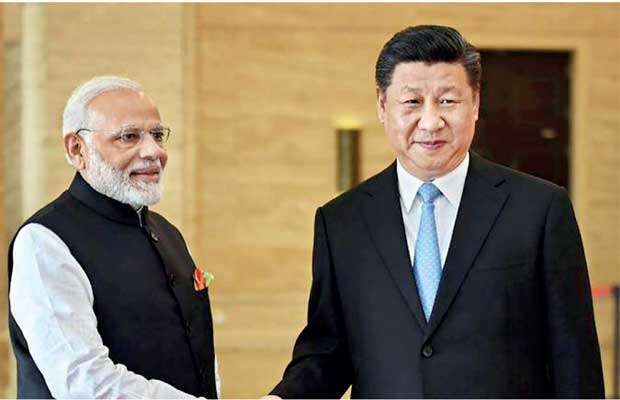

Following India’s vociferous criticism of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2017, New Delhi now avoids any such public criticisms. Rather, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s keynote address at the Shangri-La Dialogue had an accommodative tenor, although he referred to Chinese expansionism in a subtle manner. This should not be understood as a pro-China tilt but simply alludes to New Delhi’s attempts to chart its own balancing path in the Indo-Pacific. India’s deepening engagements with Japan and the United States do not appear to be directed towards escalating tensions with Beijing.

New Delhi’s motivations seem to emerge from the conviction that a pragmatic foreign policy can focus on exploring avenues of cooperation even if contentious issues exist. With both nations already sharing a disputed border, it would be in India’s interest to avoid challenging China in the wider Indo-Pacific region. Modi’s warming up to China may aim to avoid Doklam-esque events around the 2019 elections. Alternatively, such events could mobilise nationalist sentiments that contribute to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s popularity, as the Doklam episode demonstrated Modi’s resolve to withstand Chinese pressure.

China’s reorientation forms part of its overall efforts to minimise region-wide frictions that not only affect its relations with Indo-Pacific nations but have also give the BRI a bumpy ride. Besides the ongoing militarisation of the South China Sea and growing accusations that China is using the BRI for debt and espionage purposes, its acquisition of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port in December 2017 has only contributed towards the growing international backlash against China.

Criticism on China’s expansionist designs

In the Indo-Pacific region, Australia, New Zealand and Malaysia have openly criticised China’s expansionist designs. Even the BRI’s grandiose plans and the charm of Chinese credit and infrastructure projects have not been able

to overshadow the threats of the BRI.

This year, the Australian government launched a review of its intelligence agencies after allegations of Chinese espionage came to light. Australia then banned Chinese firms ZTE and Huawei from providing Australia’s 5G network. Canberra’s fears were compounded by unconfirmed reports that China planned to build a military base in Vanuatu.

Similar concerns were voiced by New Zealand. For the first time, New Zealand formally acknowledged the multidimensionality of Chinese threats that range from China’s military build-up in the South China Sea to its debt-driven influence on Pacific island nations. Malaysia shelved three Chinese projects that were worth US$22 billion amid debt concerns.

New Delhi’s choice to avoid officially endorsing the growing international antagonism against China provides Beijing with breathing room. India still refuses to participate in the BRI but its criticism is subdued when compared to its aggressive stance in 2017.

There are initial signs of improvement in India and China’s economic relations after China agreed to import Indian rice in July 2018, a move to check India’s widening trade deficit with China. While it is too early to interpret China and India’s growing convergence of interests as a strategic shift, this dynamic could be a tactical manoeuvre between New Delhi and Beijing.

(Courtesy East Asia Forum)

(Prateek Joshi is a Research Associate with VIF India, a New Delhi-based public policy think tank)