Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

A customer likes to view, feel, look for alternatives, check the prices and at times bargain before buying a product. Sadly not so, when we buy utility services, particularly electricity and water supply. These, as the economists call, are ‘natural monopolies’.

A customer likes to view, feel, look for alternatives, check the prices and at times bargain before buying a product. Sadly not so, when we buy utility services, particularly electricity and water supply. These, as the economists call, are ‘natural monopolies’.

Telecommunication services too were a natural monopoly but with cheaper mobile communication, that monopoly has been dismantled. In electricity and water supply, too, many countries have allowed customers to choose their electricity supplier: how come? Are there two sets of wires along the road, run by competing companies? Not really; more on that in a later article.

Water can be felt but feeling electricity is dangerous. Yet, electricity and water too can be costed. Both commodities can be conveniently measured. Alternating current can be measured easily with a non-contact device. So, if the flow of the current is measured, it is possible to calculate how much of energy is delivered to each customer.

With modern electronic meters, the flow of energy can be measured all the time and transmitted to a central computer. Thereby, the electricity supplier knows how much of electricity is used by which type of customer, at what times of the day. That helps to charge him for the operating costs of the electricity supply.

The infrastructure to produce and deliver electricity is not cheap. Power plants require large investments. The accelerated Mahaweli project completed in 1990 cost US $ 1 billion. Norochcholai power plant completed more recently in 2014 was even more expensive at US $ 1.4 billion. The Upper Kotmale hydropower project too was expensive for its size, at US $ 400 million.

Electricity produced at where the resource is, must be transported to where people live and work. This needs investments on transmission and distribution. In addition to conveying electricity, the transmission network keeps the electricity generators working together, to improve reliability of electricity supply.

The lines too are not cheap; one kilometre of a transmission line may cost about Rs.40 million. Finally electricity is brought to the customers’ doorstep, which requires investments on transformers and road-side distribution lines.

The Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) states that its total asset base is Rs.700 billion. Lanka Electricity Company (LECO), the state-owned but private distributor, states that its asset base is about Rs.20 billion. There are many private power plants, both fossil and renewable and they too have invested heavily.

These assets must be expanded, upgraded, replaced and rehabilitated to serve the growing demand. Loans taken to build them must be repaid with interest. Power plants must be maintained well, to ensure reliability and efficiency.

All these cost money and who should pay that money? Of course, the customer. Investors need a return on their money. The CEB and LECO are state-owned; the CEB is directly owned by the Treasury and LECO is owned by a host of state institutions.

The CEB’s and LECO’s returns (meaning profits) are regulated by the Public Utilities Commission (PUC); private investors’ returns are not regulated but expected to self-regulate through competitive bidding each time a power plant is opened for private investors.

So, how much does it cost, to give you that precious unit of electricity, to your home, factory and office or to that street light and the temple lights that sometimes glow all-day. Who checks these costs and say “that’s fine”?

The Electricity Act of 2009, approved after being discussed for 10 years or more, empowered the PUC to be the economic regulator. A system was established for the CEB and LECO to submit their costs to the PUC for approval: a full submission once in five years to cover the larger, slow-moving assets base and a six-monthly submission on generation costs that change more rapidly. In other words, fixed costs are submitted once in five years and operating costs are updated once in six months.

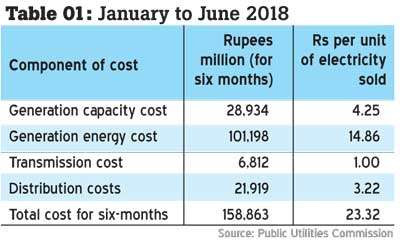

Despite some shortcomings and assumptions, the submission of costs and the approval process have been functioning since 2011. Table 1 shows the “approved” costs as published by the PUC for the first half of 2018.

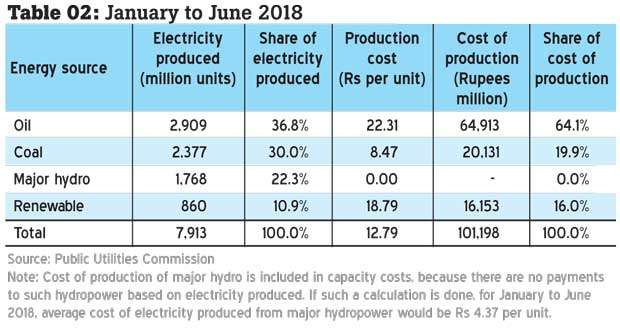

These costs are nothing but exorbitant! With the depreciation of the currency since these figures were calculated in early 2018, some of these costs would further increase. Any analyst would say take on the highest component of the cost and examine what is wrong. It costs Rs.14.86, that is 64 percent of costs as energy costs. That is to pay for oil, coal and renewable energy. Now let us look at the energy costs in some more detail. (See Table 2)

Therefore, oil-fired generation is the most expensive, followed closely by renewable energy. Coal is in the third place and finally the cheapest is large hydropower. Renewable energy, meaning wind, solar, biomass and mini hydro, are not cheap, in addition to their problems of intermittency and seasonality, which require another power plant to be on standby, just in case the wind stops blowing, the sun stops shining.

Although the trend is toward decreasing costs of renewable energy, saddled with legacy contracts signed at high prices and solar rooftop energy surplus still being paid Rs.22 per unit, the cost of renewable energy will not drop below Rs.18.79 per unit any time sooner.

Burning oil does not benefit anyone. Burning coal keeps the overall costs down. Renewable energy, though expensive, has other benefits such as lower environmental impacts. So what should be done to arrest the high cost of producing electricity?

Three options

We have three options: replace as much of oil use with a cheaper fuel; the obvious choice is liquefied natural gas (LNG), which was on a declining price trend over the past 10 years. Although the LNG prices are linked to world oil prices, it is now cheaper to get a unit of electricity produced from LNG than from oil. It was no so 10 years ago.

The second option is to reduce the costs of renewable energy, which private investors, including households can continue to build. Competitive bidding for renewable energy projects can reduce costs, as proven in bid prices announced for wind and solar power plants over the past two years.

The third option to reduce costs is to build more coal power plants.

Many countries exercise all the three options to serve the growing demand. Japan, Australia, China, Hong Kong, the USA, UK or closer to home, Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. All follow all the three options vigorously and keep their electricity costs approximately between 50-70 percent of costs of electricity in Sri Lanka.

However, for over a decade, Sri Lanka appears to be searching for these options, starting power plant projects and then cancelling them, citing abrupt policy changes and finally implementing quick solutions. That quick solution has been and will be to use more and more oil to produce electricity.

This trend of delaying major decisions and finally building oil power plants in the face of a crisis is not new but should change at least now. There is no country in the world, including the mighty oil producing countries that produces 37 percent of her electricity from oil.

With not a single lower-priced power plant not under construction since 2010, the oil share can only go up and not down, for the next five years. The impact on the economy is already severe and would further aggregate.

(Dr. Tilak Siyambalapitiya graduated from the University of Moratuwa specialising in electrical engineering. He holds a PhD in Electric Power Engineering from the University of Cambridge, UK. He has worked as an international energy consultant, leading a consulting company RMA Energy Consultants since 1999. He was President of the Sri Lanka Energy Managers’ Association from 2004 to 2006)