Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

While Sri Lanka is recovering from its worst economic crisis since independence, significant concerns remain as 42 percent of the households still adopt food coping strategies, which severely affect both the quantity and quality of protein consumption.

While Sri Lanka is recovering from its worst economic crisis since independence, significant concerns remain as 42 percent of the households still adopt food coping strategies, which severely affect both the quantity and quality of protein consumption.

Pulses are rich in quality and quantity of proteins. However, pulses comprise only 8 percent of Sri Lanka’s per capita protein supply.

Also, the per capita availability of pulses for consumption in Sri Lanka through local production and imports is just over half the recommended quantity for a balanced diet. Against this backdrop, this article analyses the trends in pulse production, consumption requirements, trade and associated policy options to provide recommendations for sustainable pulse production to meet the dietary consumption and nutritional requirements of Sri Lanka’s growing population.

Pulse production at crossroads

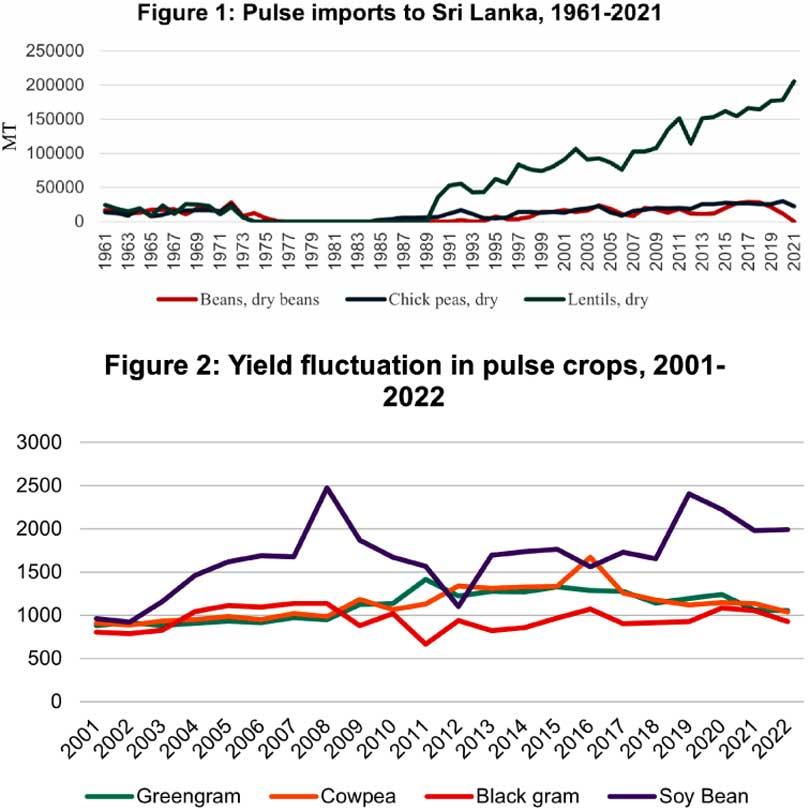

Over the years, the cultivation of pulses in Sri Lanka has undergone notable shifts. The area under pulse cultivation increased by 7.87 percent from 1974 to 1990 but decreased by 1.56 percent during 1991 and 2022. Similarly, the overall pulse production increased by 8.31 percent between 1974 and 1990 but exhibited a meagre growth rate (0.09 percent) from 1991 to 2022 (Table 1).

Pulses currently occupy less than one percent of agricultural land. The daily recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of pulses for an average sedentary man is 40 grammes (15 kilogrammes/year/person) But the current domestic production of pulses contributes 1.7 kilogrammes/year/person, which is a mere 11 percent of the requirement.

Steep rise in pulse imports

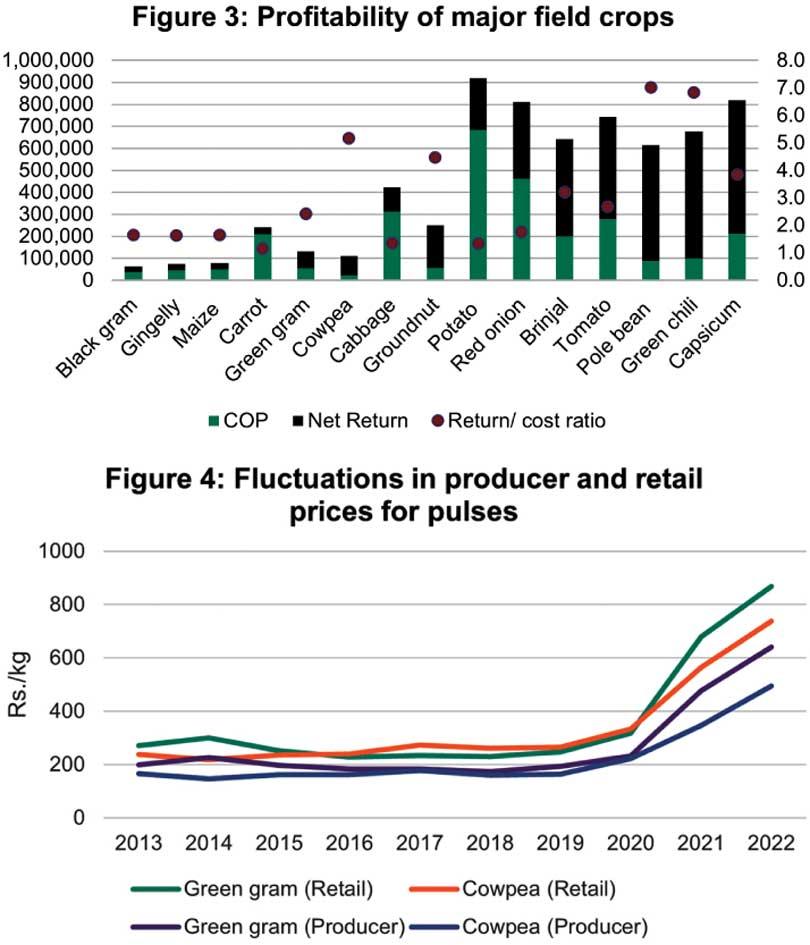

The pulse trade is an important strategy to meet the Sri Lankans’ dietary requirements. During the 1960s, Sri Lanka imported up to 50,000-60,000 metric tonnes of dry beans, chickpeas and dry lentils. But between 1974 and 1990, these imports were negligible until they started to rise in the 1990s (Figure 1).

This increase can be attributed partly to the introduction of alternative pulses such as lentils and the low prices of these alternative sources in international markets. However, the total pulse imports contribute 6.8 kilogrammes/year/person, which is about 46 percent of the requirement.

Productivity and efficiency gaps

The local supply of pulses through domestic production and imports amounts to 8.5 kilogrammes/year/person (58 percent of the requirement). Filling this gap merely by increasing the production of pulses locally is challenging, due to the existing productivity and efficiency gap. All Sri Lankan pulses have a huge efficiency gap (EG) relative to the leading producing regions globally (Table 2).

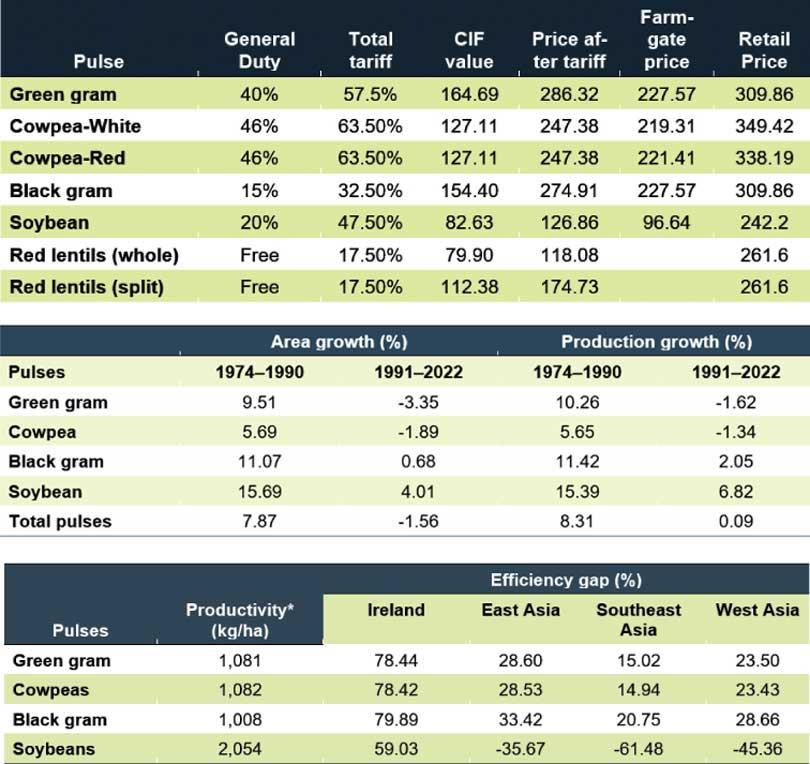

Bridging this gap is challenging since pulse productivity declined for the past six years after remaining stagnant since the 2010s (Figure 2). Moreover, this has led to low returns on investments for most of the pulses (Figure 3).

Squeezing farmgate prices

Price stagnation is a common phenomenon in pulse trade (Figure 4). Since 2019, both the producer and retail prices have trended upward, due to the external pressures from the COVID-19 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s deteriorating macroeconomic situation. However, poor marketing facilities and unstable prices coupled with a widening retailer-producer price gap have placed the pulse producers in a precarious position.

On the other hand, the farmgate price of pulses is lower than the import price after the imposition of the tariff, indicating a very protectionist system (Table 3). Such protectionist policies to safeguard the local farmers may not be conducive to the long-term growth of the sector and to ensuring food and nutrition security in the country.

Given the current level of pulse production in Sri Lanka, reviving the pulse sector will require both short and long-term strategies to address the various challenges, including poor agricultural practices, inappropriate government policies, market dynamics and climate change.

The short-term goal should be to improve production and productivity gradually while filling gaps in supply to achieve dietary requirements through imports. The import basket should include pulses like red lentils that do not compete directly with local pulses to meet the population’s protein requirements, especially the poor. Imports can also help fill the supply gap and stabilise the prices. The long-term strategies in increasing the role of pulses in generating rural income and providing food security must focus on coordinated efforts involving policy support, research and extension and market and demand considerations.

All these efforts should especially focus on areas with a huge untapped potential like diversifying the sector with underutilised pulse crops like kollu, pigeon peas and chickpeas in dry upland cropping systems and increasing pulses’ area with improved input use efficiency under the ‘pulse in rice fallow’ method. Successfully marketing pulse crops in Sri Lanka depends on crop quality, market demand, pricing and effective distribution channels, which can be achieved by improved collaboration among the value chain stakeholders, promoting value addition, market intelligence through digital technologies, improved storage and transport facilities and consumer education and awareness on pulses’ benefits and how to incorporate them into meals.

To learn more, read the policy brief on ‘Should Sri Lanka Attempt to Achieve Self Sufficiency in Pulses?’ by Kiruthika Natarajan, Manoj Thibbotuwawa and Suresh Babu. (Dr. Kiruthika Natarajan is an Assistant Professor at the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University in Coimbatore, India and a Visiting Researcher at the International Food Policy and Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC, USA. Her research interests and expertise include rural development, agricultural development, food security, climate change and impact assessment.

She has a PhD from the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University in Coimbatore, India. Dr. Manoj Thibbotuwawa is a Research Fellow at the IPS with research interests in agriculture, agribusiness value chains, food security and environmental and natural resource economics. He holds a BSc (Agriculture) with Honours from the University of Peradeniya, an MSc (Agricultural Economics) from the Postgraduate Institute of Agriculture at the University of Peradeniya and a PhD from the University of Western Australia.

Dr. Suresh Babu is a Senior Research Fellow and Head of Learning and Capacity Strengthening at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in Washington DC, USA. His research includes human and organisational strengthening of food policy systems, policy processes and agricultural extension in developing countries. Over the past 23 years at IFPRI, Dr. Babu has been involved in institutional and human capacity strengthening for higher education and research in many countries in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. He earned both his Master’s Degree and PhD in Economics from Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa)