Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

The year 2020 saw close to 1.6 billion students from over 180 countries being kept out of schools for extended periods of time, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the commendable efforts by many countries to put in place alternative remote learning strategies and corrective measures, learning losses have been unavoidable and substantial.

The year 2020 saw close to 1.6 billion students from over 180 countries being kept out of schools for extended periods of time, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the commendable efforts by many countries to put in place alternative remote learning strategies and corrective measures, learning losses have been unavoidable and substantial.

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics estimates that by early November 2020, the world student population had lost between 41 percent and 68 percent of in-person schooling they would have received under usual circumstances.

In this second year of the pandemic, many countries are moving from emergency responses towards policies aimed for recovery. Along with reopening schools and resuming education, these also include tailored support to help students adjust to learning in the new normal and remedial measures to make up for lost learning.

Sri Lankan schools have been largely dysfunctional for over 15 months since the initial closures in March 2020, despite some brief periods of operation.

This article examines the policy responses adopted in Sri Lanka’s education sector over the past year, with a view of informing its future education recovery strategy in 2021 and beyond.

School closures in perspective

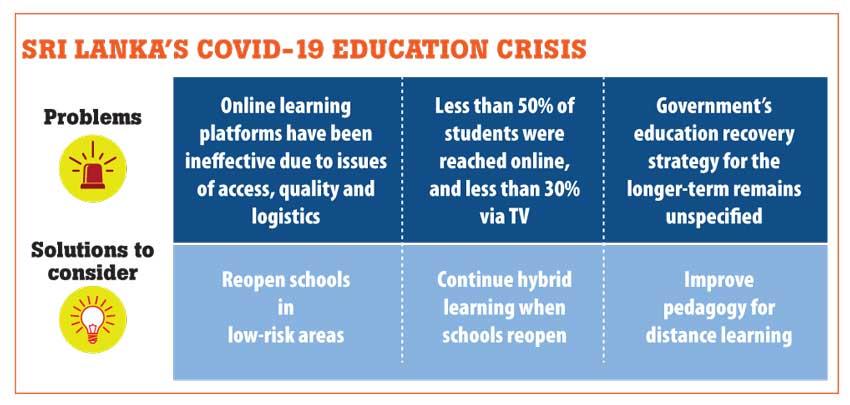

As of March 2021, Sri Lankan schools are estimated to have been fully closed for 28 weeks and partially closed for 15 weeks. As shown in Figure 1, these numbers– especially of full closures – and as a result, the share of total school days missed, are significantly higher compared to all country income group averages. These figures are likely to considerably increase further, given the current indefinite closures following the third wave of the pandemic.

Immediate response: Distance education

Immediate response: Distance education

The government’s response to current school closures is to encourage schools to continue and further expand online programmes, which have been in operation since last year. However, as cautioned in a previous Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) article, online learning platforms in Sri Lanka suffer from issues of access and quality, also confirmed by estimates of a recent survey conducted among public school teachers and parents across the country.

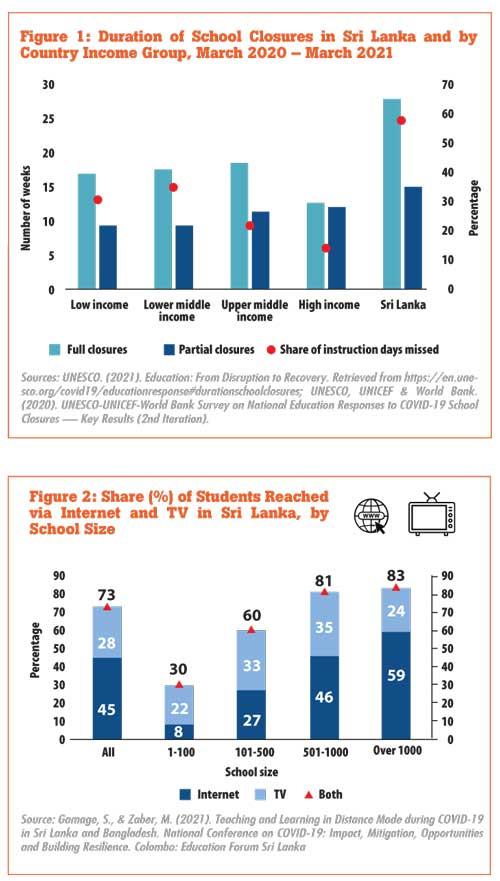

As Figure 2 shows, less than 50 percent of students were reached online on average; further, it ranged from a low of 8 percent in the smallest schools – which are typically the least privileged – to 59 percent in the largest.

The survey also indicates that education via TV proved to be a better way of reaching students in smaller schools. However, several pedagogical and logistical challenges have hindered effectiveness. These include lack of links between televised programmes and teachers’ lesson plans, a passive teaching style and absence of interaction with students, confusion of timing and duration of different subjects and TV channels and poor communication of programme information to schools, students and parents.

Long-term response: Recovery strategies

The government’s strategy for recovering learning losses in the longer term also remains unspecified. Interviews conducted with education sector stakeholders revealed that some privileged schools have initiated remedial measures at school level, leveraging available resources and support from community networks.

These include: (1) assessing student learning via Google Form assessments and telephone follow-ups, (2) monitoring student progress on attendance, work submitted and marks obtained for assessments and (3) reducing curricula content to help students and teachers cope better. Apart from lower access to resources, centralised decision-making has made it difficult to implement similar school-level measures in less-privileged schools.

Areas for urgent action

The above discussion suggests that both emergency and recovery measures adopted in Sri Lanka during COVID-19 school closures have worsened the existing education inequities. To alleviate the current education crisis and commit to leaving no one behind, urgent action is needed in the following areas:

Reopen schools in low-risk areas

It is useful to consider opening schools in remote COVID-19 low-risk areas where distance learning is neither accessible nor effective, which usually have smaller student populations, allowing for better adherence to health guidelines such as physical distancing.

This can be done by allowing schools to make decisions in discussion with relevant school committees and regional education authorities, as opposed to blanket decisions made at the central level for all schools. Such plans should also involve strategies for more permanent ways of keeping schools open, supported by regular cost-effective testing of both teachers and students and vaccinating teachers as a priority group.

Continue hybrid learning when schools reopen

The periodic interruptions to school reopening attempts underscore the need for a well-developed hybrid system for education delivery – consisting of a mix of in-person and remote options – so that teachers and students can shift smoothly to distance learning during an emergency. Even when schools are open, safety measures would not permit all students to attend school daily in highly-populated schools, necessitating blended learning to ensure uninterrupted learning.

Recent research based on different country experiences shows that effective hybrid learning can be offered in any setting, by identifying the best combination of education modalities, learning material and methods of communication, in line with available resources, skills and technology.

Improve pedagogy for distance learning

Distance education is here to stay in some form or the other, at least in the foreseeable future. Ensuring effective remote pedagogy is particularly challenging for TV broadcasts as opposed to online teaching, where programme design has to ensure continuity in the face of the central teacher. Given that TV is the most feasible way of reaching less-privileged students in Sri Lanka, is it crucial to address the existing pedagogical and logistical issues.

Reviewing measures taken in countries such as Pakistan and Vietnam to overcome similar challenges can be useful in this regard. These include:

Leveraging school teachers, subject experts and timetabling specialists to develop TV lessons aligned to the national curricula

Organising mass communication campaigns such as teaser videos and social media and newspaper advertising, leveraging public figures like politicians

Maintaining communication between schools and parents by telephone, online teacher-parent meetings and home visits for updates of learning progress.

(This article is based on the comprehensive chapter on education in the IPS’ forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2021’ report)

(Ashani Abayasekara is a Research Economist at the IPS with research interests in labour economics, economics of education, development economics and microeconometrics. She holds a BA in Economics with First Class Honours from the University of Peradeniya and a Master’s in International and Development Economics from the Australian National University. Thisali de Silva is a Research Assistant at the IPS. She holds a BA in Economics with First Class Honours from the University of Colombo. She is the first recipient of the Saman Kelegama Memorial Research Grant, awarded by the IPS, for her research on three-wheeler drivers in Sri Lanka. Thisali holds a Diploma in Applied Statistics from the Institute of Applied statistics, Sri Lanka (IASSL) and a Certificate in Business Accounting-CIMA)