Sri Lanka, which has been sending workers abroad for employment for decades, is now faced with the formidable challenge of repatriating large numbers of migrant workers affected by COVID-19.

Having successfully brought back students from China, the UK, Australia and South Asia and pilgrims from India, the authorities are now making plans to repatriate large numbers of

migrant workers.

But, unlike bringing home students and pilgrims, this upcoming repatriation exercise involving migrant workers calls for a continued coordination with the returnees, beyond the period of travel and quarantine. This article dissects the nuances of labour migration, lost foreign employment opportunities and repatriation brought about by the spread of COVID-19 and provides policy recommendations to successfully re-enter foreign

labour markets.

Need to return and repatriate

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in Sri Lankan-origin migrant workers returning to the country in large numbers, during the first half of March 2020. The influx of returnees up to mid–March comprised mainly workers in South Korea, Italy and other European countries.

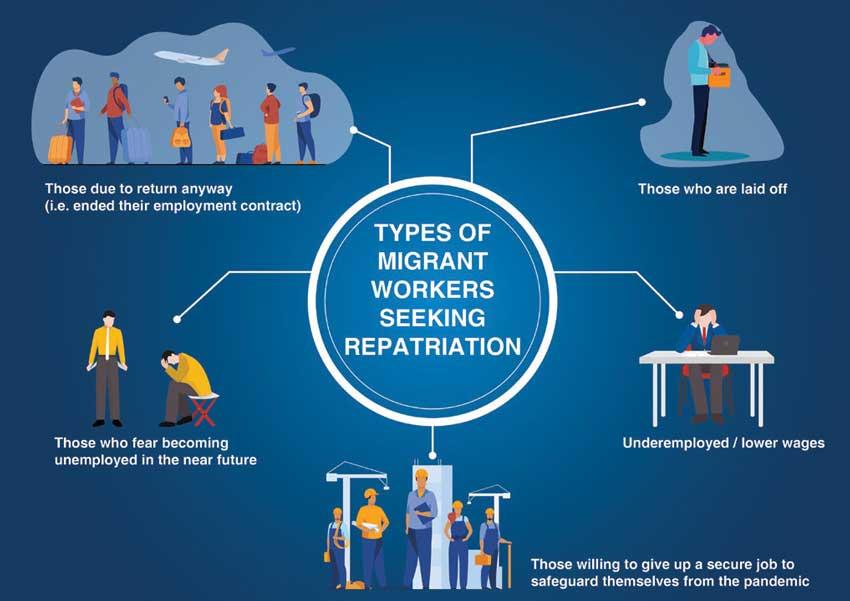

But, with the closure of the Sri Lankan air and sea ports for arrivals on March 19, many were unable to return. As of mid-May, the number of migrant workers waiting to return to Sri Lanka has further increased. This includes those without jobs in their countries of destination, possibly due to being laid off as a result of the economic downturn caused by the pandemic and those who have ended their employment contract and were due to return anyway.

Additionally, it includes migrant workers still holding a job but underemployed or fear becoming unemployed in the near future and those who are willing to give up a secure job to safeguard themselves from the

raging pandemic.

The latest estimates show that around 17,000 migrant workers and their families are trying to return to Sri Lanka and the government has planned out a meticulous scheme to repatriate them. This involves prioritising those hoping to return based on the countries of destination and within countries, prioritising based on the type and the situation of these migrant workers.

For instance, repatriation from Kuwait will be fast-tracked to make use of the amnesty granted to those without valid entry documents. At the same time, the government is nudging the migrants who are still holding a job to reassess their situation in their countries of destination and consider their plight in Sri Lanka

once returned.

Halted departures

Even though most migrant workers who are planning to return are still outside the Sri Lankan labour market, the domestic labour market is already affected by the stock of ‘would-have-been’ migrant workers. Specifically, compared to the approximately 15,000 Sri Lankans who left for foreign employment in April 2019, in April 2020, there were zero departures of migrant workers, as the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign employment (SLBFE) temporarily banned the departure of migrant workers registered with them.

May 2020 also appears to be a lost month in terms of foreign employment, while in March 2020, only about a half of the planned departures occurred (around 7,500). As such, from mid-March to end of May, the missed foreign employment opportunities for Sri Lankans amount to around 37,500 jobs. All these ‘would-have-been’ migrant workers add to the displacement in the Sri Lankan labour market, as they are unemployed for all intents

and purposes.

Domestic labour market

Regardless of the returning migrant workers and those who could not take up their planned foreign jobs, the labour market in Sri Lanka has been feeling the impact of COVID-19 in many ways. For instance, hundreds of thousands of informal sector workers immediately became unemployed or underemployed with the economic shutdown on March 20. Now, private sector employees are hit by the unemployment/underemployment wave. In short, even without factoring in the returning and the ‘would-have–been’ migrant workers, the Sri Lankan labour market was already in turmoil from COVID-19.

Way forward

With a growing unemployment rate, Sri Lanka should rapidly start programmes to address the unfavourable repercussions of the pandemic on the labour market. In doing so, special strategies should be developed to handle unemployment associated with migrant workers.

As such, just as the government has invested time and resources to carefully plan a large-scale repatriation exercise of migrant workers, it has to be complemented with a detailed plan to address the resulting labour

market challenges.

‘Would-have-been’ migrant workers

1. Ensure they retain their skills and training until they can be redeployed.

i. The SLBFE to provide online programmes or short videos to help them maintain their skills and training.

2. Redirect them towards reskilling and upskilling activities and provide appropriate certifications.

3. Contact their ‘would-have-been’ employers and find out about the availability of the same

employment opportunity.

If above employment opportunity is still available, plan out a rapid deployment plan, without losing this opportunity to another sending country.

If above employment opportunity is no longer available, explore the possibility of negotiating a new employment package (wages, benefits, etc.) with more flexibility to facilitate the employer to hire the same ‘would-have-been’

migrant worker.

Returning migrant workers

1. Ensure that returning migrant workers have received their service letters and other such credentials, as well as payments and benefits.

2. Provide Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) certification.

3. Deploy them, as appropriate, towards skills development of those unemployed in Sri Lanka.

4. Assist their socio-economic reintegration.

Migration sector

1. Lift the SLBFE’s current temporary ban on departure for foreign employment for all countries, as this restriction only applies to those registered with the SLBFE and the continuation of the ban further deepens the dichotomy among registered and unregistered

migrant workers.

i. Instead, impose the ban on a list of selected countries, with selection to be done on a scientific/medical basis.

2. Maintain regular contact with employers of returning migrant workers and overseas recruitment

agencies through:

i. Sri Lankan diplomatic missions.

ii. Recruitment agencies in

Sri Lanka.

3. Explore possible measures to encourage overseas employers to retain Sri Lankan migrant workers.

i. Alternative working arrangements, telecommuting.

4. Introduce an attractive, streamlined, flexible and speedy mechanism for overseas employers to rehire laid off Sri Lankan workers as well as to hire new employees.

i. Provide additional flexibility for employers who have previously employed Sri Lankan workers.

(Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the authors, email

[email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)

Sri Lanka, which has been sending workers abroad for employment for decades, is now faced with the formidable challenge of repatriating large numbers of migrant workers affected by COVID-19.

Sri Lanka, which has been sending workers abroad for employment for decades, is now faced with the formidable challenge of repatriating large numbers of migrant workers affected by COVID-19.