Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Although COVID-19 may be gender-blind, it has created a crisis that has disproportionately affected women across the globe. The economic impact of the pandemic is mostly channelled through the labour market.

Although COVID-19 may be gender-blind, it has created a crisis that has disproportionately affected women across the globe. The economic impact of the pandemic is mostly channelled through the labour market.

Estimates show that women’s jobs are 1.8 times more vulnerable than men’s jobs and while women make up 39 percent of global employment, they account for 54 percent of overall job losses. While many factors affect the vulnerability of women’s employment during the pandemic, existing gender gaps in the labour market, women’s employment share in highly-affected sectors, the ability to telecommute and the amount of unpaid care work carried out by women have been identified as the main determinants.

In this context, this article examines women’s vulnerability in the Sri Lankan labour market due to the sector they are employed in.

It also looks at gender-based employment segregation – a key factor behind women’s overrepresentation in certain industries and underrepresentation in others – and proposes policy measures to address this imbalance.

Impact of COVID-19 on employed women in SL

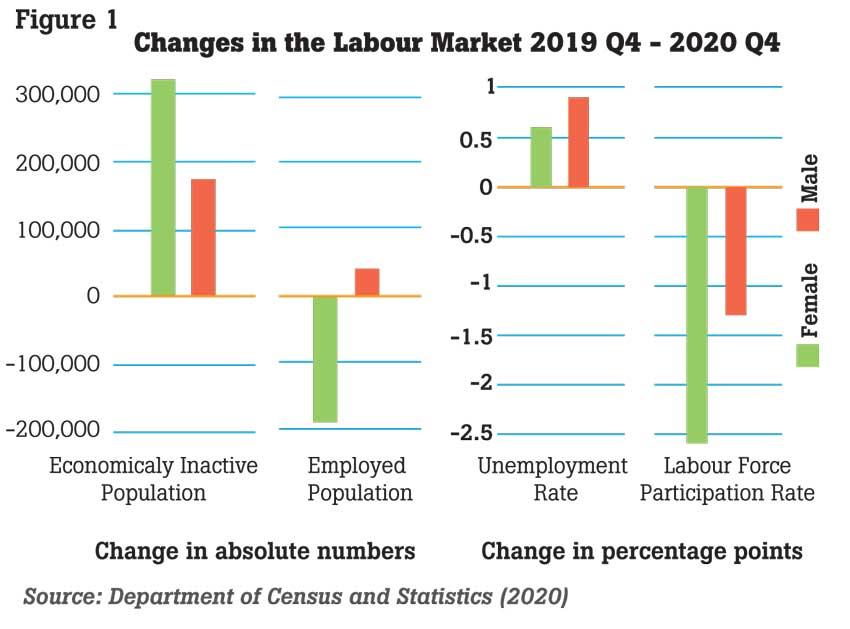

A comparison of labour market figures and indicators for Sri Lanka for the fourth quarters of 2019 and 2020 shows a severe impact on women (Figure 1).

While the absolute number of employed men has increased by 38,938, the number of employed females has decreased by 189,148. The number of economically inactive persons has increased between the years. Females account for 64 percent of that increase in economically inactive persons. The labour force participation (LFP) rates for both sexes have decreased significantly but the fall is more prominent for women. The unemployment rate has increased for both sexes during the period, whereas the increase for men is marginally higher than that for females attesting to the lowered LFP of women.

Sector matters

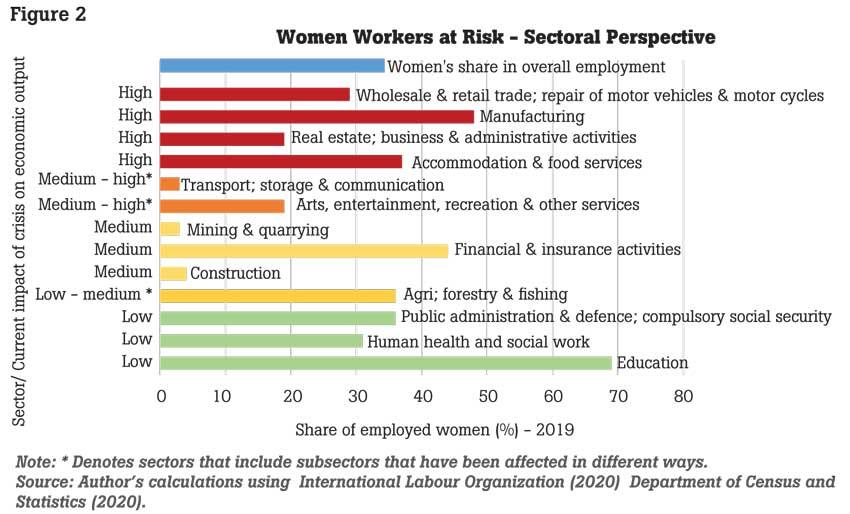

The greater impact on employed women due to the pandemic is linked directly with the sectors they are employed in. Calculations of the author on women’s employment in Sri Lanka based on an assessment by the International Labour Organisation indicate that their employment share is high in both low-risk and high-risk economic sectors (Figure 2).

Manufacturing (including the sub-sector of textile manufacturing), accommodation and food services and wholesale and retail are high-risk sectors with relatively high female employment shares.

Female representation is relatively high in some medium-high risk and medium risks sectors such as ‘arts, entertainment, recreation and other services’ and ‘financial and insurance activities’, respectively, as well. Even though health is a low-risk sector, women employed in the health sector face a higher risk of contagion.

Gender-based employment segregation

Gender-based employment segregation – ‘the unequal distribution of men and women across and within job types’, is often the major reason for women’s (or men’s) over-representation in certain sectors. In most cases, especially for females, their choice of employment is linked with the traditional gender roles they play in society (i.e. direct and indirect care responsibilities such as caring for children, the elderly and the sick, cleaning, cooking, shopping and fetching water and fuel).

For example, in Sri Lanka, the female share in several frontline occupations is high (i.e., health professionals, health-related professionals and care workers). These occupations are directly linked with women’s traditional gender roles.

Gender-based employment segregation creates unfavourable labour market conditions such as gender gaps in wages, job quality and employment trajectories. Demand-side factors, as well as supply-side factors, limit women’s choice in selecting an employment sector, thus causing employment segregation. Gender gaps in skills and qualifications, domestic and care responsibilities, safety (i.e. harassment at workplaces and when using public transport) issues and lack of role models and networks are some important supply-side factors.

Gender biases in recruitment, evaluation and promotion processes, employers’ perceptions of women employees (where employers perceive women employees as more suitable for certain types of jobs) and features of the workplace culture are important demand-side factors.

Way forward

Both training in hard skills and soft skills would increase women’s chances of securing employment in fields traditionally dominated by males. Specific interventions that reduce and redistribute women’s domestic and care responsibilities (i.e. expanding access to key infrastructure for care and investing in labour-saving technology and redistributing care responsibilities between men and women within households and between households and state and other institutions) would lessen the burden of care responsibilities borne by women. This would create an enabling environment for women to participate in labour market activities and to expand the array of employment options available for them.

Strengthening the legal framework and law enforcement mechanisms is important to ensure the safety of working women both at the workplace and when travelling to work. Furthermore, promoting female role models who have succeeded in traditionally male-dominated sectors would inspire women to choose such careers.

In addition, establishing workplace cultures that practice gender-blind recruitment, evaluation and promotion processes are needed to curtail the demand-side factors of gender-based employment segregation.

(Sunimalee Madurawala is a Research Economist at the IPS. Her research interests include health economics, gender and population studies. Sunimalee holds a BA (Economics Special) with First Class Honours and a Masters in Economics (MEcon) from the University of Colombo. She can be reached at [email protected])