Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

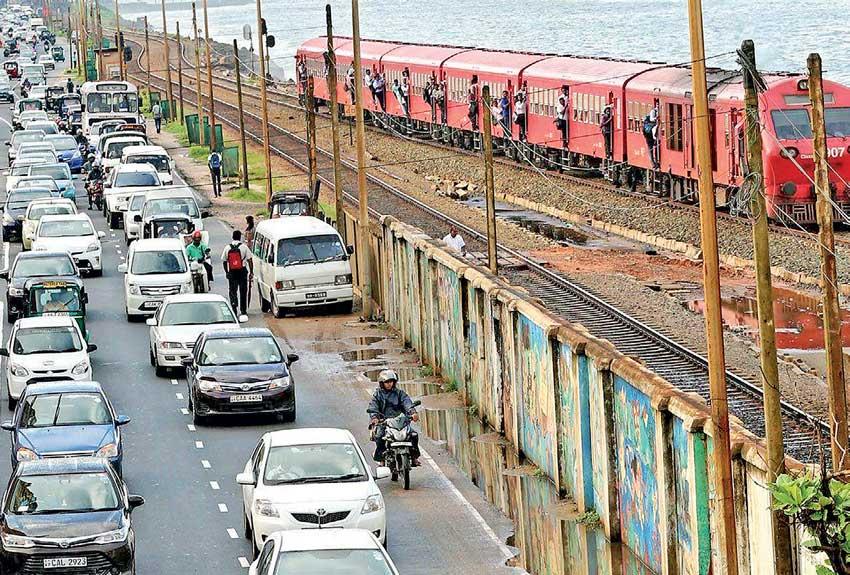

Private motorisation has been Sri Lanka’s preferred mode to solve its mobility needs. Not much thought has been given to the public transport systems in recent times, which over the years were systematically neglected and relegated to the poor to use.

Private motorisation has been Sri Lanka’s preferred mode to solve its mobility needs. Not much thought has been given to the public transport systems in recent times, which over the years were systematically neglected and relegated to the poor to use.

Although the country’s Western province is a high-density region with 1,690 people per square kilometre, overall, Sri Lanka is a high population density country, with 329 people per square kilometre on average. Most provinces in the dry zone have less than 200 people per square kilometre, falling into the medium density.

But for our population of 21.6 million, Sri Lanka has around 5.6 million vehicles in operation (cumulative registrations are higher at over eight million). Our vehicle-person ratio is approximately 1:4 or precisely 26 vehicles per 100 people.

While motor vehicles are an asset for development, their overuse can bring about misery not only through high energy bills but also through traffic congestion and air pollution, which impacts health issues and reduces liveability, especially in urban areas.

Interestingly, the transportation policies of countries with high-income status (over US $ 30,000 per capita income), have managed their motorisation very successfully. Countries that have mismanaged this sector, on the other hand, continue to languish in the middle-income status. Therefore, the analogy ‘if a country mismanages its transport; it mismanages the economy’, is fitting. The middle-income countries are bound to end up in the so-called middle-income trap because a motorisation-based lifestyle would create a drag on their respective economies. This seriously impedes economic growth that would enable them to escape the middle-income status.

Many low-density countries with less than 50 people per square kilometre have used high levels of motorisation to reach their economic objectives. In all these cases, they have over 70 vehicles per 100 people. On the other hand, medium to high density developed countries have maintained 40-60 vehicles per 100 people, while the only two developed countries with a population density higher than 1000 people per square kilometre have used stringent policies to keep their motorisation below 15 vehicles per 100 people.

Given these figures, it is established that Sri Lanka has 50 percent more vehicles than it should — an alarming prospect, in the face of our current economic crisis and resultant fuel shortages, which are nothing short of dire.

Is it not urgent then to call for an immediate realignment of our motorisation policy, especially taking into account the high figure of our private vehicles? For a start, we might want to promote public transport in the Western province and all urban centres outside as well, while encouraging the affordable use of private vehicles in areas with less population. In the meantime, we should also maintain balance in other areas.

Another aspect that we need to pay attention to is the quality of our public transport, which has been allowed to deteriorate. Upgrading the public transportation systems to their fullest potential, with new management and technology, similar to what countries like Singapore, South Korea or Hong Kong have done, will ensure more people using this mode of travel. Most countries build in a tax for fuel that goes to assist in developing public and alternative modes of transport. This should also be an important aspect of our fuel policy, as improved public transport means more people using it, which would automatically help in reducing our massive fuel costs.

Recently, there were efforts to introduce urban transport with LRTs and metros. While these showpiece projects are attractive, they come at too heavy a price, especially in our current economic scenario. Also, mobility problems are not centred in Colombo alone; they need to be improved across the country. Spending lavishly on one corridor, say for example Parliament Road or the expressway to Kandy, would not solve the problem.

If Sri Lanka is to align itself to the successful path high-income countries have taken, we need to stop living beyond our financial ability. We need to slow any further growth of our motor vehicle fleet until we reach the US $ 8,000 per capita income mark, especially since we are already bearing the burden of having 50 percent more vehicles than we should have.

Before the pandemic, we have been spending an average of US $ 1,126 million per year, for the import of private vehicles. The influx of these private vehicles is partly responsible for the push for road building, which has also cost the country dearly. With the added cost of fuel at the current dollar rates, if Sri Lanka is to continue its current motorisation policy, it will cost us approximately US $ 2 billion per annum. This is not including the cost of trucks, buses and land vehicles, which make up only around 20 percent of all vehicle imports. Therefore, private vehicles should have the most significant number of restrictions through a policy reversal.

It is in Sri Lanka’s best interest to discourage the unrestricted import of vehicles, particularly those for private transport. It is not only a saving of our fuel bill through better use of public transport and cycling and walking, etc. but also a check on sizable foreign exchange outflows, which we cannot afford.

(Prof. Amal Kumarage is a transport sector professional, with over 35 years of experience in academia, government and consulting. He is a Senior Professor in the Department of Transport and Logistics Management, University of Moratuwa, a Chartered Engineer and a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport and Founder President of the Sri Lanka Society for Transport and Logistics. He is a graduate in Civil Engineering from the University of Moratuwa. He completed his PhD at the University of Calgary, Canada)