Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

With the recent publication of the Central Bank annual report 2020, we are now in a position to ascertain how the Sri Lanka economy performed during the previous decade (2010-2019) as well as the first year of the current decade (2020). We may note in this regard that (a) the country on the whole has been free of violent ethnic conflict during the past 11 years and (b) there have been no significant acts of domestic terrorism during this period, with the exception of the Easter Sunday bombings of 2019, which killed over 250 civilians on the west coast and depressed economic growth during the remaining part of that year, due to its adverse impact on tourism and net foreign capital inflows. This was the first major macroeconomic shock the island received since the ending of the civil war in May 2009.

With the recent publication of the Central Bank annual report 2020, we are now in a position to ascertain how the Sri Lanka economy performed during the previous decade (2010-2019) as well as the first year of the current decade (2020). We may note in this regard that (a) the country on the whole has been free of violent ethnic conflict during the past 11 years and (b) there have been no significant acts of domestic terrorism during this period, with the exception of the Easter Sunday bombings of 2019, which killed over 250 civilians on the west coast and depressed economic growth during the remaining part of that year, due to its adverse impact on tourism and net foreign capital inflows. This was the first major macroeconomic shock the island received since the ending of the civil war in May 2009.

Approximately a year later came the second macroeconomic shock – far worse than the first, as the entire country went into lockdown, due to the advent of the coronavirus, which has taken the lives of over 3,000 Sri Lankans to date. So far, the island has been hit by three waves of COVID-19, which has forced the government to impose periodic hard lockdowns in all parts of the country, some short, some long, i.e. a few days versus several weeks, respectively. The most recent islandwide lockdowns occurred in May and June this year. Never before has the global economy experienced a combined health and economic crisis on such a gargantuan scale. COVID-19 has killed around four million people to date and driven a large number of poor nations to the brink of economic and social collapse.

The virus originated in Wuhan, one of China’s wealthiest cities and rapidly engulfed the entire planet. As one country after another went into soft or hard lockdowns, the global economy began to shrink at an alarming rate, thereby causing a massive loss of livelihoods. Ironically China (where it all began) was the only country to register positive economic growth in 2020.

Economic performance in previous decade (2010-2019)

The main objective of this article is to examine Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic performance, both before and after the advent of COVID-19 and to assess whether the economy is capable of recovering from the hammer blow delivered by the pandemic, given the inward-looking nature of the policy environment created by the present political leadership, which has been in power since November 2019.

One of the key indicators of overall economic progress is the growth of gross domestic product (GDP). For Sri Lanka to achieve a major economic transformation, GDP must grow at over 6 percent per annum on a sustained basis. During the past three decades, the only South-Asian nation to have done so was India. Some readers may be surprised to learn that India is now the world’s fifth largest economy, ahead of England, France, Italy, Brazil and Canada, in that order. It is important to note that India’s quantum leap from low to high GDP growth occurred only after the country abandoned its inward-looking policy orientation in favour of an outward-looking policy stance, which entailed far-reaching structural reforms. The architect of India’s economic liberalisation, which commenced in the early 1990s, was Finance Minister Manmohan Singh – a progressive, Oxford-educated economist, who later served as Prime Minister for two consecutive

terms (2004-2014).

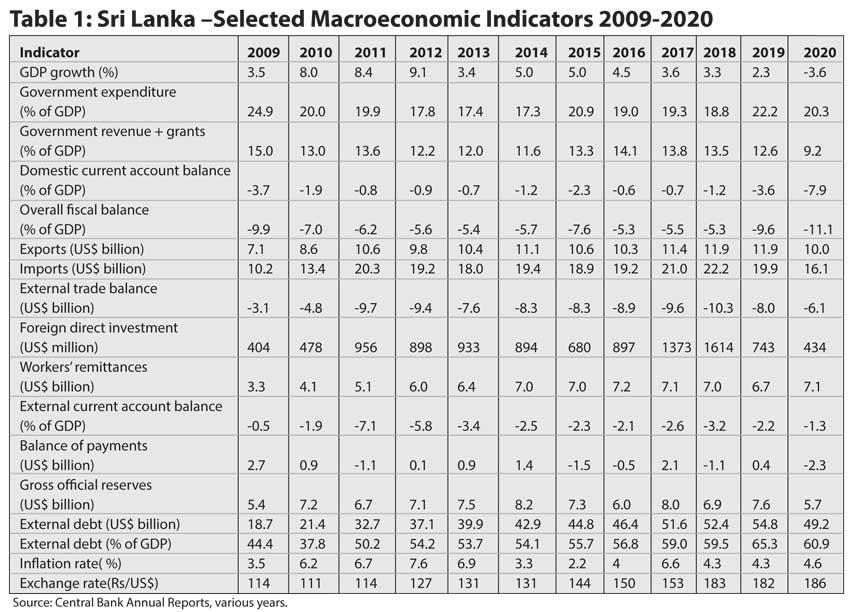

While India grew so rapidly as to overtake England and become the world’s fifth largest economy in the previous decade, how did Sri Lanka perform during the same period? As Table 1 shows, though GDP growth was impressive during the first three years (2010-2012), it has by and large been erring on the low side since then. After 26 years of internecine ethnic conflict, peace returned to the island in mid-2009, which largely explains why the country underwent rapid economic expansion during the initial,

post-war period.

The rebuilding of physical infrastructure, revival of production and marketing activities, and restoration of livelihoods commenced briskly in the former war zone (North and East), which prior to the war, accounted for a sizeable share of the island’s total agricultural output in the non-plantation, fisheries and livestock sectors. There was also a surge in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows and workers’ remittances during this period. From 2010 to 2012, annual GDP growth averaged 8.5 percent but from 2013 to 2019, it averaged only 3.9 percent.

It was assumed by the government that once peace returned to the island, there would be a rich dividend in the form of massive FDI inflows. But this did not occur. In 2009, FDI inflows amounted to only US $ 404 million. By 2011, they had increased to US $ 956 but after the initial spurt, they became erratic and exceeded US $ 1 billion in only two years (2017 and 2018). This temporary hike was largely due to a debt-to-equity swap with China Merchants Port. As FDI inflows started to wax and wane, so did GDP growth. The economy began to run out of steam, so to speak and the lack of a stable macroeconomic policy climate only served to aggravate the situation by dampening private sector growth.

Another reason why GDP growth began to decline after 2012 is that though exports increased significantly, imports grew at a faster rate. Hence, net exports were negative throughout the previous decade with the ballooning trade deficit exerting severe stress on the balance of payments (BOP). During this period (2010-2019), exports and imports averaged 5.7 percent and 8.1 percent growth per annum, respectively. Thus, on average, growth of imports exceeded growth of exports by 2.4 percent per annum. Moreover, in three of the 10 years under scrutiny, export growth was negative. In 2010, imports exceeded exports by US $ 4.8 billion. By 2018, this gap had widened to US $ 10.3 billion. In 2019, it narrowed to US $ 8 billion, not because exports increased but because imports decreased due to a significant hike in the import duty on luxury cars.

In 2010, tea and garments accounted for 55.6 percent of total exports, respectively. By 2019, the ratio had declined to 51.8 percent but it goes to show that the island is still heavily dependent on these two commodities to drive exports. All in all, the extent of diversification of the export base in the previous decade was modest, due to the absence of a viable, medium to long-term export development strategy designed to make the Sri Lankan economy globally competitive. Without large inflows of FDI on a regular basis, it is unlikely that the island could build a robust and diversified export base.

Key policy and institutional constraints

There are several reasons why foreign investors, on the whole, are staying away from Sri Lanka, which include the following: (i) poor quality economic infrastructure, which raises the costs of doing business; (ii) weak macroeconomic fundamentals, such as negative external and domestic current account balances, ballooning external trade and fiscal deficits, continual exchange rate depreciation, a high external debt to GDP ratio and depleted foreign reserves; (iii) the volatile and ad hoc nature of government policy formulation leading to a great deal of uncertainty in the business environment; (iv) a weak institutional and legal framework for facilitating and supporting FDI in export-oriented economic activities; (v) inadequate financial and institutional support for applied research and development across all sectors; (vi) the unwillingness of successive governments to address serious land and labour market distortions; (vii) a wide range of trade barriers (including import bans/restrictions on hundreds of goods), which severely decreases overall economic efficiency and last but not least, (viii) a volatile political climate. Over time most of these constraints have steadily worsened, which does not augur well for Sri Lanka’s future economic development, keeping in mind the extent to which the pandemic has disrupted global trade and investment.

Economic performance in 2020

In 2020, due to the severe economic disruptions caused by a hard, islandwide lockdown from March 21 to June 1, GDP growth plummeted into negative territory. A recent World Bank report entitled Sri Lanka – Economic and Poverty Impact of COVID-19 (April 2021) notes that the economic contraction commenced in the first quarter of 2020 with GDP registering minus 1.8 percent growth. The corresponding figure for the year as a whole was minus 3.6 percent. What is clear is that the economy was already in bad shape when the first COVID-19 wave hit the island in the latter half of March and that the ensuing health crisis/lockdown simply made things worse.

The above report estimates that the US $ 3.20 poverty rate increased from 9.2 percent in 2019 to 11.7 percent in 2020. In absolute terms, the number of additional people pushed into poverty by the pandemic exceeded half a million. The increase in the poverty rate occurred mostly in the rural areas of Kandy and Ratnapura districts, where it was already high. As stated succinctly in the above report: “This implies that the COVID-19 crisis may have slightly shifted the composition of the poor but did not fundamentally change the nature of poverty in Sri Lanka, as most of the poor continue to live in predominantly rural areas.”

The economy on the whole has been performing poorly during the past four years. Some of the key macroeconomic indicators shown in Table 1 (GDP growth, ratio of government revenue plus grants to GDP, domestic current account balance, overall fiscal balance, gross official reserves, foreign direct investment and the exchange rate) were weak in 2019 and continued to deteriorate further in 2020. To rebuild an economy that has undergone a severe contraction and facilitate robust private-sector development is a daunting task for the government in the context of the pandemic. Sadly by sending out mixed signals, it has failed by and large to gain the trust and confidence of the private sector.

Need for structural adjustment

What is extremely worrisome is the inward-looking, protectionist ideology embraced by the present regime. The last government to adopt the same stance was the left-of-centre regime that came into power in 1970. The experiment with a closed economy was such a disaster that the ruling party was soundly beaten at the General Election of 1977. The first thing the new right-of-centre government did was to liberate the economy from the shackles of socialism and facilitate rapid private-sector development.

The massive trade barriers erected since the pandemic began are seriously impeding GDP growth – a frightening scenario given that COVID-19 has taken the economy to the brink. The recent ban on chemical fertiliser imports, for instance, is likely to create havoc in the agricultural sector. The ruling party needs to take a close look at what happened from 1970 to 1977 and avoid repeating the same mistakes, if it wishes to prevent a serious erosion of its rural voter base.

Can the government solve the current economic crisis? At the core of the crisis is the external debt trap from which the country is unable to extricate itself. The government has adopted a borrow to pay old loans strategy to avoid defaulting on foreign debt service payments exceeding US $ 4 billion a year. The situation is grave as foreign reserves are currently hovering at roughly the same level. Currency swaps and other ad hoc policy measures (including restricted private-sector access to foreign exchange) will only buy time and further aggravate the crisis.

Even if these measures enable the government to meet its debt service obligations this year, it faces the grim prospect of defaulting on the external debt next year. The need for debt restructuring and structural adjustment is therefore critical at this time. The government needs to work with an external agency to remove serious market distortions, strengthen macroeconomic fundamentals and restore public debt sustainability through prudent fiscal management and revenue mobilisation. According to the above World Bank report, Sri Lanka’s ratio of government revenue plus grants to GDP (12.6 percent in 2019) is one of the lowest in the world.

When Imran Khan was in the opposition, he was a vocal critic of the IMF. He also viewed foreign aid as a curse. After becoming the Prime Minister of Pakistan in August 2018, he was dismayed to find that the economy was hopelessly embedded in a vicious external debt trap. He had no choice but to swallow his pride and seek an IMF bailout, which came in the form of a US $ 6 billion Extended Fund Facility.

Perhaps our political leaders can take a leaf out of Imran Khan’s book. They need to move quickly in order to avert a full-blown BOP crisis, which the country can ill afford at this time, given the oppressive and unpredictable nature of the pandemic. If a fourth wave hits the island in the midst of a severe BOP crisis, the economic and poverty impact will be catastrophic.

(Seneka Abeyratne, a retired economist/international consultant to

ADB/Manila, can be contacted [email protected])