Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Sri Lanka ratified the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in November 2003. The FCTC is a global treaty developed in response to the health consequences of tobacco consumption and the formidable power exerted by the vested interests of the tobacco industry.

Sri Lanka ratified the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in November 2003. The FCTC is a global treaty developed in response to the health consequences of tobacco consumption and the formidable power exerted by the vested interests of the tobacco industry.

Recognising the undue influence exerted by the tobacco industry over policymakers, the FCTC builds in an explicit safeguard in the form of Article 5.3, which states: “In setting and implementing their public health policies with respect to tobacco control, Parties shall act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry in accordance with national law.”

Although Sri Lanka has ratified the FCTC, it has not yet given effect to Article 5.3. Thus, tobacco policies remain vulnerable to influence by commercial and vested interests. A previous Insight by Verité Research – ‘Who’s responsible for ‘Alternative Facts’ on tobacco taxation?’ revealed signs of undue industry influence on media. This Insight discusses signs of undue industry influence on the bureaucracy and policymakers in Sri Lanka. It then recommends strategies that can be employed to begin shielding these policies from influence. The recommendations reinforce the importance of giving fuller effect to the FCTC to ensure that tobacco policy is not compromised.

Sri Lankan context

In Sri Lanka, the cigarette industry consists of a monopoly producer – Ceylon Tobacco Company (CTC). As a monopoly producer, CTC has the power to exert concentrated influence on decision makers on taxation and regulation.

The interests of CTC in Sri Lanka are for the most part in direct conflict with the national interest in terms of both public health and public revenue. CTC benefits when people smoke more, start smoking at a younger age and are addicted to smoking. The national interest in public health suffers on all three counts. On any given cigarette price, CTC benefits when the percentage of tax is lower, while the state coffers benefit when it is higher.

In such a situation, where there is a huge trade-off between public interest and company interest, it is important that the decision makers are not subject to undue influence by the company. Such influence is what the FCTC seeks to protect against through Article 5.3 of the FCTC. However, there are strong indications that failing to give effect to Article 5.3 has created an environment in which the bureaucracy in Sri Lanka is subject to the undue influence of vested interests.

Signs of influence on bureaucracy

In a previous Insight, Verité Research pointed out that “none of the financial institutions in Sri Lanka, from the Finance Ministry, to the Treasury to the Central Bank, follow a coherent method or formula for the taxation or pricing of cigarettes”.

The mistaken positions, which emerged in media, as set out in the first Insight referred to above, is echoed by the bureaucracy of the Finance Ministry despite data and analysis proving the contrary, contributing to poor management of cigarette tax revisions. There are three reasons to be concerned about the advice and actions of the bureaucracy.

Concern 1: Allowing cigarette tax to price ratio to decline over time

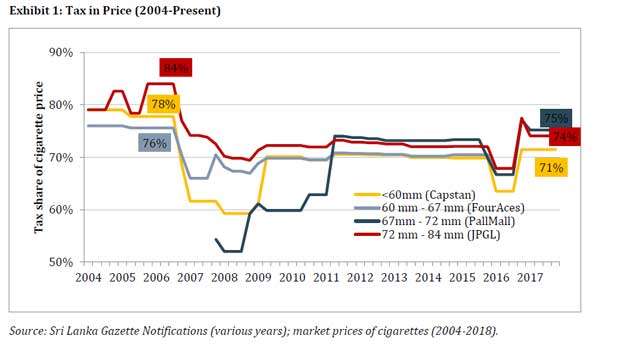

Exhibit 1 shows how the tax to price ratio on cigarettes has fluctuated and declined significantly post-2005; it declined further after 2015, before corrective action to increase the excise tax and reintroduce the VAT) was taken in October 2016. This action came after the tax to price ratio for cigarettes declined by 4 percent in 1Q-3Q 2016 (see Exhibit 1), even while the government increased the VAT on all other goods by 4 percent (cigarettes remained exempt from VAT).

Concern 2: Resisting highly beneficial corrective action on taxes

The corrective action taken in October 2016 was a success for the government in terms of increasing revenue, as well as reducing consequences on public health (despite media reports to the contrary). The annual report of the tobacco company itself stated that consumption of cigarettes declined by 18.4 percent and revenue to government increased by Rs.17.6 billion from excise tax and VAT from 2016 to 2017.

The action was initiated by a Cabinet paper introduced by the Health Ministry, supported by the National Authority on Tobacco and Alcohol, despite contrary written advice presented to cabinet by the Finance Ministry, which delayed the policy by several months.

Concern 3: Perpetually failing to adjust taxes despite revenue benefits

There has always been clear evidence that for cigarettes, the percentage reduction in consumption is significantly smaller than the percentage increase in price/tax. This was reconfirmed in the aftermath of the 2016 tax increase. This means that a price/tax increases always lead to higher revenue.

VR’s Insight titled ‘The hidden side of cigarette pricing’, published on May 23, 2018, shows how the tobacco industry has understood this relationship and increased the net-of-tax price faster than the government has increased taxes, since 2005. Industry profits have also kept increasing accordingly. This shows that the industry has calculated correctly the positive revenue implication of price increases.

Nevertheless, in the last 18 months, the Finance Ministry has chosen to keep the tax on cigarettes unchanged, despite introducing significant tax increases on personal incomes, commercial businesses and essential commodities, on the basis that the government was struggling to meet revenue targets.

The trajectory of advice and actions by the Finance Ministry in Sri Lanka set out in the above concerns does not appear to be aligned with the national interest of either public health or public revenue. This pattern begs the question: what is the influence exerted by vested interests on the positions taken by the Finance Ministry and how can that influence be reduced in favour of the public interest?

Combating influence on tobacco policy: three forms of disclosure

A start to combating interference on tobacco policy in Sri Lanka can be made by applying the FCTC Article 5.3 and following the relevant WHO guidelines on its implementation. These guidelines have been synthesised into the three forms of disclosure presented below.

1. Disclosure of industry actors: Requires that tobacco industry actors or those working to further its interests reveal themselves through a process of registration (This measure is derived from Principle 2 of the WHO FCTC guidelines.)

2. Disclosure on communications: Requires that all communications between tobacco industry actors and policymakers be recorded and disclosed (This measure is derived from Principle 3 of the WHO FCTC guidelines.)

3. Disclosure on conflicts of interest: Requires that any type of incentive or benefit including services and funding provided to policymakers, political parties, journalists and media organisations by the tobacco industry (or those working to further its interests) be disclosed by all parties to the exchange. (This measure is derived from Recommendation 2 of the WHO FCTC guidelines).

Although these three measures alone will be unable to fully address the problem of the industry’s influence on tobacco policy, they may reveal undisclosed connections that allow for influence to take place. Once such connections are identified, more stringent measures can be taken, such as those recommended by the FCTC to restrict communications and preventing conflicts of interest between policymakers and the tobacco industry. Thus, setting up requirements on disclosure could be a sensible way for Sri Lanka to begin the long journey ahead in mitigating the influence of vested interests on tobacco policy.

(Verité Research is an independent think-tank based in Colombo that provides strategic analysis to high level decision-makers in economics, law, politics and media. Comments are welcome. Email [email protected])