Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

In simple terms, money printing is issuing new money to the economy by a Central Bank- also known as “reserve money”.

In simple terms, money printing is issuing new money to the economy by a Central Bank- also known as “reserve money”.

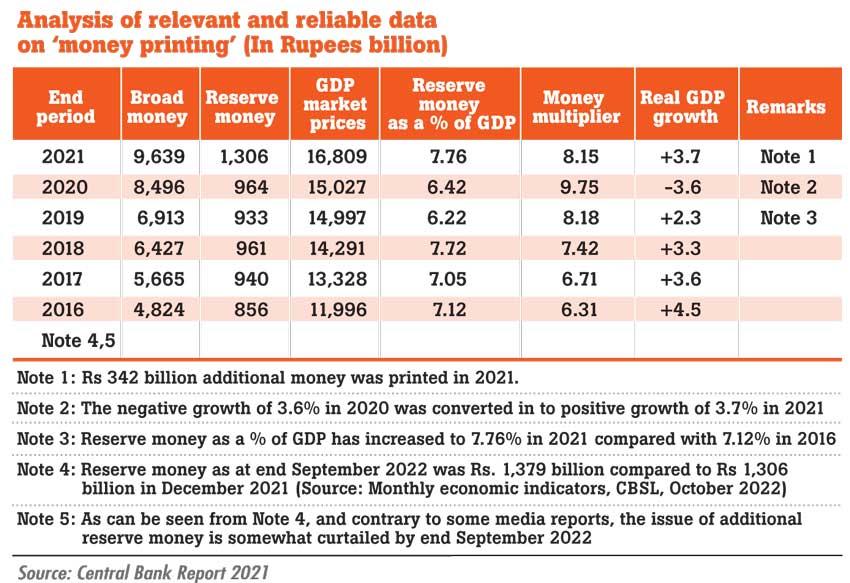

Some people seem to mistakenly believe it’s only the Treasury bills bought by CB. We need to understand the relationship between money printing and ‘reserve money’ and how to analyse data and quantify whether there has been any excessive money printing or not.

The management of reserve money is the most important indicator in managing the proper liquidity position and inflationary expectations. After estimating the economic growth, central banks used to add new money to the economy in order to meet the amounts of growing transactions.

If more money is printed than required, it will increase the demand for goods and services, thus creating inflationary pressures in the economy. On the other hand, policy makers can adopt relaxed monetary policy by increasing the money supply to stimulate economic growth, especially when there is a ‘deficient demand’ in the economy.

Rationale of issuing new money

The government and Commercial banks receive foreign exchange through export proceeds, tourism, inward remittances from expats and foreign loans/FDIs etc. These foreign currencies are usually sold to the Central Bank in order to meet the rupee requirements by com banks/Treasury.

When foreign exchange is purchased by the Central Bank from commercial banks/ government, the Central Bank issues rupees. Through this mechanism, the CB adds new money or ‘reserve money’ to the existing money stock of thecountry. Similarly, when making foreign debt repayments by the Central Bank in foreign currency, the government should pay an equal value of rupees back to the Central Bank. It, then reduces the existing money stock incirculation -it reduces the level of reservemoney. These are positive features.

In addition to foreign exchange transactions, the Central Bank can also influence the total stock of money in circulation through domestic rupee transactions with the commercial banks and the government, for example; to make salaries and pension payments etc.

When the government issues Treasury bills to finance its budgetary needs, the Central Bank under the provisions of the Monetary Law Act could purchase part of TBs at the request by the government. In order to make payments for the Treasury bills purchased, CBSL should issue new money in rupees equivalent to the value of the Treasury bills purchased. The higher the budget deficit, the higher would be the take up of T bills by CBSL and hence the increase in reserve money.

This is where new money is created and put out to the system by CBSL. That’s why expenditure cuts by GOSL are critical for monetary stability including the exchange rate stability. Another important aspect is, CBSL can also absorb part of new money or reserve money issued to the GOSL or markets by engaging in open market operations (OMO). When CBSL sells T bills from its portfolio, markets will part with the Rupees in their hands (absorption of liquidity).

The reverse takes place when CBSL provide rupees and purchase T bills from the market (injection of liquidity) as explained earlier. This is where the government ‘expenditure cuts’ are important, including a strategy to reduce government and public debt to curtain interest payments.

Daunting task in curtailing borrowing spree & money printing

It can be seen from above, contrary to some media reports and statements in parliament recently, the issue of new money (additional reserve money) is somewhat curtailed in 2022. An attempt has been made to reduce the budget deficit by way of increase in taxes in the government budget 2023 and tightening monetary policy of CBSL.

However, it can be seen that the additional taxation revenue is totally insufficient to avoid further borrowings. In fact, the total gross borrowings in the budget 2023 is recorded as Rs. 4,979 billion in order to cover budgeted expenditure including debt repayments. This is where new money is created and put out to the system by CBSL.

It is in that context only, the urgent requirement of proper management of borrowings, as well as SOE restructuring and reducing government expenditure should be viewed. It goes without saying that debt restructuring process becomes part and parcel of the whole exercise. In this regard, it is important to critically analyse the existing stock of total debt which includes domestic debt, foreign debt including borrowings from SOEs and semi- governmental Institutions and the nature of the debt and its creditors.

Causes of debt more important than remedy

According to Central bank statements and media reports, the total Central Government debt is Rs. 24.7 trillion as of July. It is higher by Rs. 7 trillion in comparison to the end of 2021. A part of the increase could be attributed to re-pricing following the sharp depreciation of the Sri Lanka Rupee since March 7th this year.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also declared Sri Lanka’s public debt (122 percent of GDP as at end June 2022) as unsustainable. It was announced by MOF recently that a decision was taken to treat government owned business entities and semi- governmental debt as part of the total ‘government debt’.

This is in addition to the adjustments made to convert foreign debt into rupees to give effect to the unprecedented exchange rate depreciation from 8/3/22 that is understandable. Apart from the above, we need to ascertain whether they have made further adjustments to the total debt portfolio. This is becausethe total debt to GDP has skyrocketed exceeding 122 percent and Rs 7 trillion more than the figure as at end 2021.

A recent research article by Ilias Bantekas, Professor of International law and arbitration published in Bin Khalifa university under the caption “Lebanon’s public debt default: The Greek experience shows the cause is as important as the remedy” may be useful for us to be more careful in our debt restructuring efforts.

A look at Greek experience

At the time of Greece’s sovereign debt crisis, the popular belief was that successive Greek governments had augmented the public sector and had exceeded their finances and that their governments are corrupt.

According to the above research paper, an independent parliamentary committee set up in 2015 disproved this narrative.The committee’s extensive findings clearly showed that until the beginning of the global financial crisis in 2008, Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio was one of the lowest in Europe and certainly sustainable. So, why did it shoot through the roof the following year? This is because Greek banks had accumulated private debt (in the form of loans) to the tune of about 100 billion euros.

Then Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio skyrocketed and its creditworthiness declined. It now had a newly discovered debt of 100 billion euros and these facts were buried under the popular narrative. The independent research carried out suggested that in order to fully understand Lebanon’s debt crisis, it is not sufficient to simply examine the remedial measures suggested by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The origins of a country’s debt are far more important, because it tells us how the debt was accumulated and by whom.

Accordingly, Professor Ilias Bantekas advises Lebanese government as follows, quote; “No restructuring process should commence before the truth about the debt takes place. No person of sound mind would mortgage their house simply because a bank told the owner he had incurred a debt of which he was unaware. The owner would first inquire about this debt and if he found that it was wrongly or unjustly incurred, he would refuse to pay it. This is the very least the Lebanese people can demand.” Unquote.

The lesson learnt from the experience in Greece and Lebanon in debt restructuring –if I may summarise - a more comprehensive analysis of the origin and causes of debt is more important than just following debt restructuring mechanism (even though it’s highly sophisticated) in terms of IMF recipe.

(The writer is former Chairman of Sri Lanka Tea Board)