Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Sri Lanka’s low female labour force participation rate (FLFP) has received intense policy attention over the past several decades for many reasons. It is widely assumed that improving FLFP will not only empower women and reduce gender disparities but will also promote productivity and economic growth.

Sri Lanka’s low female labour force participation rate (FLFP) has received intense policy attention over the past several decades for many reasons. It is widely assumed that improving FLFP will not only empower women and reduce gender disparities but will also promote productivity and economic growth.

Over the years, a popular strategy for promoting FLFP by successive governments has been to encourage self-employment opportunities or entrepreneurship. However, FLFP has remained below 35 percent for years. Self-employment jobs are highly vulnerable to economic fluctuations as social safety nets do not cover them.

Furthermore, on average,self-employment income is lower than other types of income. This article argues that to empower women and drive economic growth, policyshould focus on facilitating women’s access to decent work over access to any job.

Measuring decent work

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), decent work refers to jobs that provide workers with dignity, equality, fair wages and safe working conditions. Further, those in decent work have a say in their work and areprotected from discrimination. The main components of decent work are workplace rights, employment, social protection and social dialogue.

However, the lack of standard indicators to measure decent work and the difficulty in capturing all aspects of decent work, make it challenging to determine the availability of decent work. For example, an aspect such as social dialogue is not easy to capture.

Despite the difficulty in measuring, it is important to understand whether the jobs performed by women in the market are decent jobs. The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) reported that in 2021, 32 percent of women aged 15 and above (or working-age women) were in the labour force. Of these, only 29 percent were employed, while the rest were unemployed.

Since there is no standard measure for decent work, several indicators with varying degrees of decent work components were used to analyse the share of working-age women engaged in various aspects of decent work. These include non-vulnerable work, full-time employment, formal employment, fair wages, and fair wages for decent working hours.

Non-vulnerable work is a relatively better type of work compared to vulnerable work. The latter is categorised as any job that contributes to family work or own account work. These types of employment are considered vulnerable because the workers depend on the revenue generated by their enterprises and are not covered by social security.

Full-time employment is defined as working for more than 35 hours a week. However, the concept of part-time work is not defined in Sri Lanka. As such, many workers in part-time employment do not receive the same benefits as those in full-time employment.

Formal employment refers to paid workers in the formal sector (government/semi-government sector; private sector firms with more than ten workers; or smaller private sector firms), excluding employees without a permanent employer or employees whose employers are not contributing to their pension or provident fund.

Fair wages are defined as the minimum wage with legislated allowances. In 2018, this amounted to Rs. 13,500 a month. According to the decent work concept, a fair wage should be earned during regular work hours, which are 45 hours per week in Sri Lanka.

Disparities in women’s access to decent work

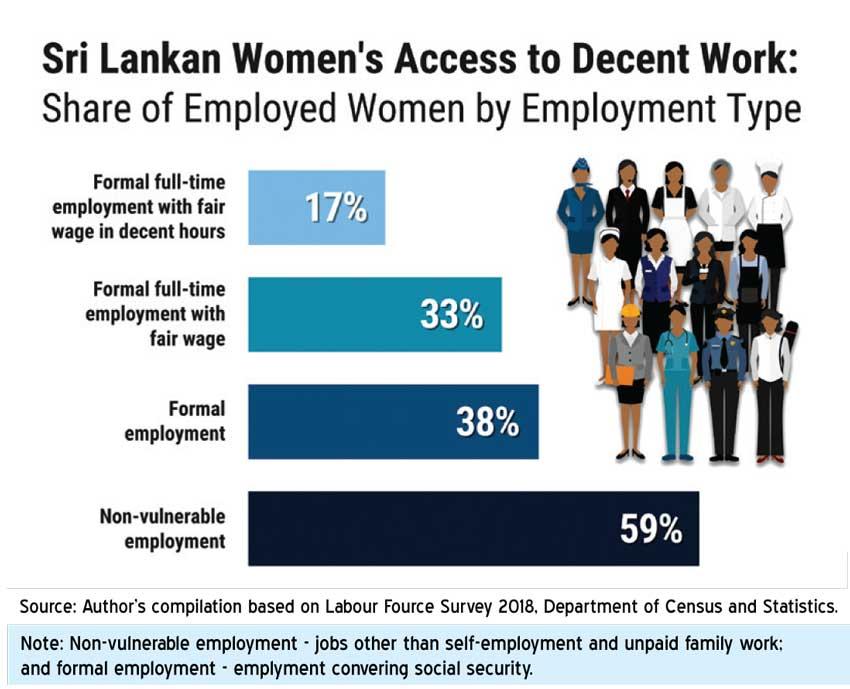

Figure 1 summarises the statistics on women employed in various aspects of decent work. The share of women engaged in decent work is significantly lower than the share of total employed, and the prevalence levels decrease as more aspects of decent work are included in the measure.

Specifically, only 38 percent of females in formal employment were covered by some form of social security. The share of employed females covered by social security and receiving a fair wage was slightly lower at 33 percent. However, nearly half of the formal full-time female employees receiving a fair wage need to work more than the legislated 45 hours to earn the fair wage. Such excessive work hours are a barrier to accessing decent work for females, given their care responsibilities at home.

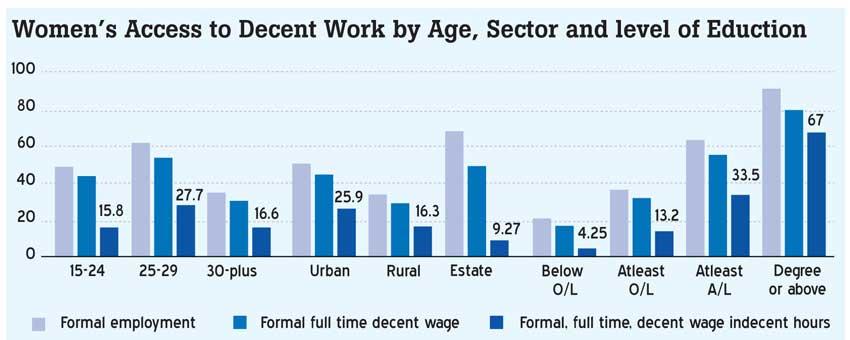

Another issue concerning access to decent work in Sri Lanka is the inequality in access. As illustrated in the Figure, access to decent work varies widely across age groups, residence sectors and education levels.

A recent study by IPS has identified several reasons, including access to quality education, access to physical infrastructure such as secure transportation and electricity, labour market conditions in the area of residence, social norms, outdated legislation and poor implementation of legislation. These inequalities in access to decent work must be eliminated to improve overall access to decent work.

As shown in the Figure, low-skilled females (those with an education level below General Certificate in Education - Ordinary Level [OL]) have the least access to decent work. However, access to decent work increases with higher levels of education.

Furthermore, access to decent work is also low for those outside the urban sector. Lastly, access to decent work is lower for females of age 30 years or more compared to females in the age group of 25 to 29. This disparity could be due to older females choosing to work fewer hours due to their other responsibilities.

Way forward

In Sri Lanka, less than 17 percent of female workers are in decent work. Access to decent work varies widely across women of different ages, from different localities, and with different skill levels. If the government intends to reduce inequality and promote growth by improving women’s access to jobs, it should prioritise promoting access to decent work. Facilitating access to other types of work is unlikely to push women out of poverty and provide them with better social security and a fair income.

According to the IPS’ State of the Economy 2022 report, improving women’s access to decent work should prioritise job creation in productive sectors. This can be achieved by investing in expanding productive sectors and innovating to improve productivity and job creation. Further, attention should be given to policies that reduce barriers to accessing decent work.

(The writer is the Director of Research at IPS. She heads the Labour, Employment and Human Resource Development unit at the IPS. Her research interests include labour market analysis, education and skills’ development, migration and development, and health economics. She holds a BSc in Computer Science and Mathematics summa cum laude from the University of the South, USA and an MA and PhD in Economics from Duke University, USA. She can be contacted via: [email protected])