By Ganga Tilakaratna

Social protection has been increasingly viewed as an important tool for addressing poverty, vulnerability, inequality, and social exclusion. Sri Lanka has a long history of providing social protection to its population. Social protection policies and programmes such as the free education and health care provision and food subsidy programmes have been implemented by the successive governments since the 1940s.

At present, there are many social protection programmes targeting vulnerable segments of the population: the poor, elderly, disabled, children and women. These programmes vary from cash and in-kind transfers to pensions, insurance, and livelihood development programmes.

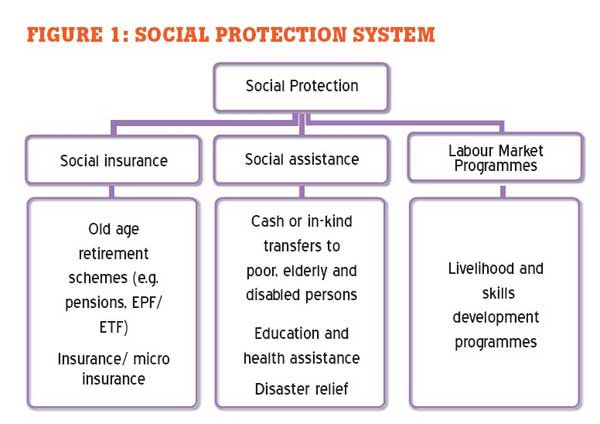

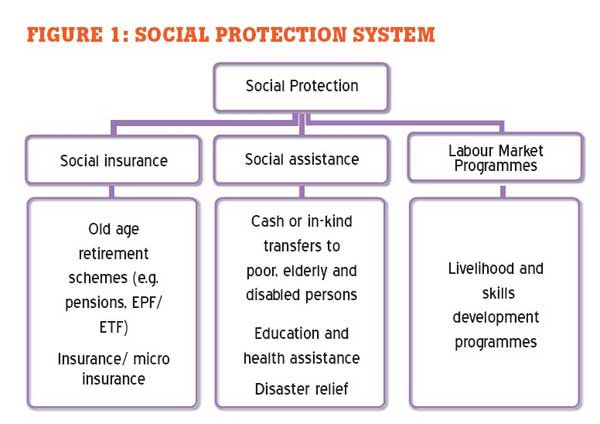

They can be broadly categorized as:

(i) social insurance,

(ii) social assistance, and

(iii) labour market programmes as shown in Figure 1.

Despite the multitude of programmes, there are several gaps and weaknesses in the current social protection system.

Low coverage and poor targeting

Low coverage and poor targeting are two most common problems in the majority of social protection programmes in Sri Lanka. Programmes designed for the poor, elderly, disabled and other vulnerable groups often cover only a fragment of the eligible population. The programmes for school children such as the free textbook and free uniform programmes that are almost universal in coverage are perhaps the only exception.

Limited coverage is largely a result of budgetary constraints.

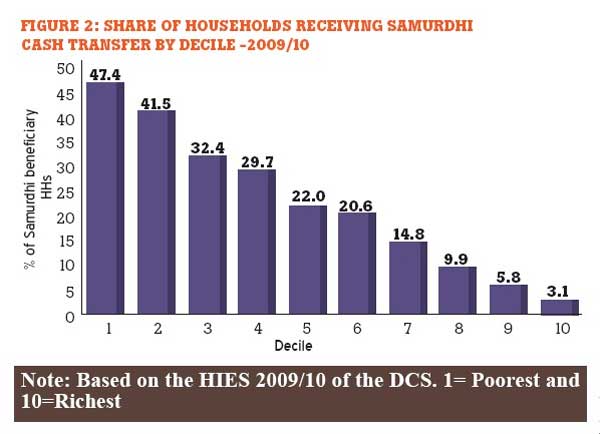

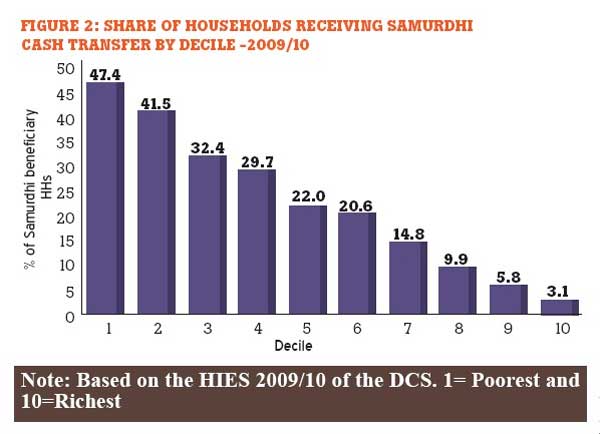

Many programmes also suffer from targeting problems. A recent IPS study reveals that only less than a half of the households in the poorest decile (47.4 percent) receive benefits under the Samurdhi cash transfer programme(see Figure 2). However, there are 3-15 percent households in the top four deciles who receive Samurdhi benefits.

These figures indicate the severity of the targeting problem of the Samurdhi programme both inclusion and exclusion errors. The extent of targeting errors of the other social protection programmes is difficult to measure owing to the lack of data. In addition, many programmes lack clearly defined eligibility criteria and an entry and exit mechanism, which too has contributed to the targeting problems in social protection programmes.

Inadequacy of benefits

The value of monthly cash transfers received under most social assistance programmes remains low. Under the Samurdhi income transfer programme, the maximum amount received by a family was Rs. 1,500 per month until the end of 2014 (while the minimum was Rs 210), which is far below the minimum requirement to meet their basic needs.

The net cash value received by a family was much lower than the above amounts since there are deductions for compulsory savings, social security and the housing fund. However, as per the Department of Samurdhi, these subsidy amounts have been increased since January 2015, with a minimum of Rs. 420 and a maximum of Rs. 3000 per month. The monthly allowances provided under the elderly assistance programmeand Public Assistance Monthly Allowance (Rs. 250 - Rs. 500) arealso far inadequate to cover the basic expenses like food. According to the national poverty line, a person requires around Rs. 3,800 per month to cover his/ her consumption expenditure at a minimum level. Budgetary constraints and inequitable resource allocation

Many social assistance programmes suffer from budgetary constraints, which restrict them from expanding their coverage and improving the benefit amounts.

Moreover, a recent IPS study reveals considerable inequity with regard to allocation of funds within the current social protection system.

Over 80 percent of the total social protection expenditure goes to retirement benefits of formal sector workers (e.g., pensions and EPF/ETF) while the expenditure on social assistance programmes such as Samurdhi, disability assistance and elderly assistance as well as expenditure on labour market programmes for vulnerable groups remain low. In particular, the study finds that pensions for the public sector workers account for about 55 percent of the total social protection expenditure. However, pensions benefit only a smaller share of the country’s elderly population.

Lack of coordination

Currently, there are several ministries, departments, and provincial councils carrying out different social protection programmes for various vulnerable groups. Lack of coordination among these institutions and programmes increases the cost of social protection provision and leads to overlaps in beneficiaries served under these programmes.

Way forward important to improve ‘targeting’ i n programmes such as Samurdhi, and make better use of the limited resources available for social protection for the benefit of the ‘neediest’ groups. This would help improve the coverage of the programmes as well as the amounts of benefit.

Moreover, strengthening the coordination among the programmes implemented by various institutions in order to minimize duplications is important to enhance efficiency and thereby improve coverage and benefit levels.

Given t he rapid ageing of population, reforms are also required for the pension scheme in order to reduce the burden on the government budget and make the programme more sustainable. Such reforms would also help release funds to extend social protection to elders who do not receive retirement benefits or any other assistance.

It is (The writer is a Research Fellow and the Head of the Poverty Unit at IPS. To view this online and to comment, visit ‘Talking Economics’ – www.ips. lk/talkingeconomics)