Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

.jpg) Post-war Sri Lanka has been looking prosperous (with high GDP growth numbers) because it was throwing a grand party for itself; first by the public on imported consumer goods, then by the state on construction materials. Unfortunately, consumption may be the only thing that Sri Lankans are contributing to their growth party.

Post-war Sri Lanka has been looking prosperous (with high GDP growth numbers) because it was throwing a grand party for itself; first by the public on imported consumer goods, then by the state on construction materials. Unfortunately, consumption may be the only thing that Sri Lankans are contributing to their growth party.

What do we know about post war growth?

Sri Lanka posted record growth rates of 8 percent and above in the first two post war years of 2010 and 2011. In 2012 growth dipped to 6.4. The Verité Insight titled “post war growth bump hits a ceiling” argued that growth in these three years came at the expense of first increasing the trade deficit and then increasing the fiscal deficit, and therefore cannot be sustained.

There is a second insight that arises from the same data.

There is a second insight that arises from the same data.

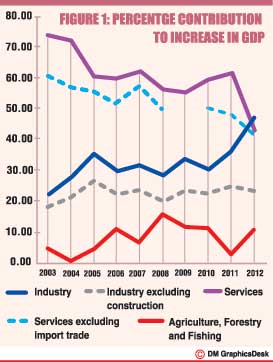

There are three main sectors into which all of GDP is categorised: Services, Industry, Agriculture (including forestry and fishing). Their share of contribution to annual increases in GDP over the last decade is shown in percentage terms in figure 1.

The post-war contribution from agriculture is low and fluctuating, generally because of weather conditions. The Services sector is the first to pick up post-war, increasing its share of GDP growth in 2010 even as the share of Industry and Agriculture declines a little. In 2011 Industry also increases its share while Services increases even further. In 2012 there is a steep decrease in share of Services but it is compensated for by a steep rise in the share of Industry. This is true in absolute numbers as well as in percentages. The insight comes from digging a little deeper.

It’s actually Import Trade, not Services

What looks like thriving growth in the Services sector really boils down to growth in just one thing. That is: Import Trade, which is the premium charged to the consumer for the services involved in selling imported goods. If a trader imported a car for one million rupees (paid to Japan let’s say), and sold it for 3 million in Sri Lanka (which includes the cost of government taxes etc.) then the addition to GDP is 2 million rupees.

When Services sector share of GDP growth is plotted without Import Trade, it is consistently decreasing in all the post-war years (see figure 1). In fact, when Import Trade withered in 2012, (see figure 2 as well, it fell from contributing 14 percent to contributing just 1.4 percent) the contribution of Services plummeted even further. Import Trade was not only driving post-war growth it was also a crutch to the declining influence of Services.

.jpg) It’s actually Construction, not Industry

It’s actually Construction, not Industry

There is a similar revelation for Industry. The growth in the share of GDP in 2011 and 2012 boils down to just one thing: Construction. When Industry sector share of GDP growth is plotted without Construction, it remains quite flat in the post-war years. That means the first two years of increase was all about Construction.

It’s ultimately imports, not local production

Import trade, depends primarily on imports, and that is no surprise. Imports can indicate healthy trends. For instance, imports of industrial inputs could signal increased production activity in the country. But unfortunately for the post-war prognosis, since Import trade is a sub component of wholesale and retail trade sector, it is mostly the import of consumer goods that has been boosting the growth numbers.

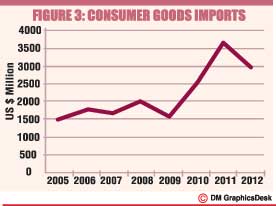

As indicated by the customs data in Figure 3 in 2010 and 2011, importation of consumer goods, has increased dramatically: by 58 percent in 2010 and by 48 percent in 2011.

More surprising and problematic might be the fact that the construction boom is also fuelling a dramatic increase in the imports, this time of construction material. In 2012 despite the dip in overall imports of the country, construction material imports in terms of quantity recorded a huge increase of 156 percent in terms of quantity and 140 percent in terms of value (see figure 4). The indication is that that local industry does not have the capacity to fabricate and provide much of the supplies needed in the construction boom.

Who is earning to pay for consumption growth?

Such import sourced growth in consumption should need an equivalent increase in net foreign income if it is to be credited as growth. But the significance of export income has been free falling in the Sri Lankan economy, from 33 percent of GDP in 2000 to 17 percent of GDP by 2012, and exports declined even in absolute value terms in 2012 and 1st half of 2013.

But what Sri Lanka does not export in production, it has sent out in the form of labour (whether it has left for economic or political reasons). The remittances to Sri Lanka from those diaspora workers was 7-8 percent of GDP during 2002-2009 and since then has increased to over 10 percent of GDP in 2012.

The labour income and home-ward concern of the diaspora workers seems to be a large part of Sri Lanka’s growth story. It’s time be aware of the fact.

(Verité Research provides strategic analysis and advice for governments and the private sector in Asia)