Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

REUTERS - A battle of wills between Iran’s government and foreign exchange traders may end with authorities taking over all legal trade in the rial, leaving many Iranians to seek hard currency illegally in a poorly supplied black market.

This arrangement would probably let the economy limp on in the face of Western economic sanctions. But it might also increase corruption, distort companies’ business decisions and fuel middle-class discontent with President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

In the past two weeks, the rial-U.S. dollar exchange rate has emerged as a fault line in Iran’s economy as the country resists foreign pressure over its nuclear programme, denying Western accusations that it is aimed at making weapons.

Changing savings

The sanctions have slashed Iran’s oil export earnings and triggered a rush by Iranians to change their savings into foreign currency, dragging the rial down. Early last week the rial was trading around 37,500 to the dollar, having lost about a third of its value in 10 days and two thirds in 15 months.For Iran’s clerical rulers, who face threats of war from abroad and widespread if subdued discontent at home, preventing any destabilizing economic crisis is a pressing concern.Many economists estimate Iran may still earn more from exports than it spends on imports, giving the state leeway to resist Western pressure, as sanctions-hit rulers in the likes of Iraq, Serbia and Zimbabwe did in the past. But a loss of trust in the rial among Iran’s private savers means the government may now limit private dealing in the currency to staunch the flow.

The slide in the rial is boosting inflation, officially at around 25 percent already, as imported goods become dearer. Last week riot police clashed near Tehran’s Grand Bazaar with crowds protesting at the currency’s drop, while Ahmadinejad is under fire from parliament for his economic management. So the government is eager to stabilize the exchange rate.

Its failure to do so in the last several days suggests it may have to close down the legal free market entirely to establish control of the currency, analysts said.

“The end result will be the government taking over currency trading, squeezing out the private traders or forcing them to bow to the government for patronage,” said Mohammad Ali Shabani, an Iranian political analyst based in London.

“This will give the government leverage as it prepares for tighter sanctions in the next 20 months.”

Currency approach

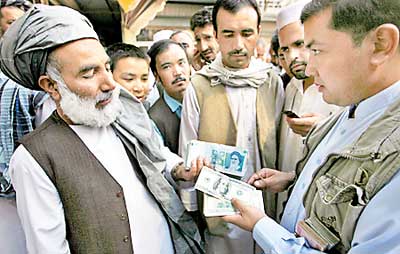

Over the last several days, the government has tried to impose its will on the currency market with a combination of threats and persuasion. The Iranian Money Changers Association, a state-licensed body, recommended its members sell dollars at 28,500 rials - a discount of about a quarter on last week’s free market rate.

At the same time, over two dozen people have been arrested on charges of manipulating the currency market - widely seen as a warning to dealers of the consequences if they quote the rial at weaker rates than those proposed by the authorities.

Traders are unwilling to lose money by selling dollars at such prices, but also fearful of official displeasure if they sell at other prices. So most free-market trade in the rial in Tehran and across the Gulf in Dubai, a major centre for business with Iran, has shut down, dealers in both cities say.

“If you go to Iran now it will be really hard to find U.S. dollars - you have to buy them in the black market,” said an Iranian currency dealer in Dubai, declining to be named because of the political sensitivity of his remarks. Analysts said the government’s likely response to the stand-off would be to shift more currency trade out of the market and into official channels.

Earlier this year it fixed an official “reference rate” of 12,260 rials at which the central bank sells Iran’s petrodollars to importers of some foods and medicines that are designated as essential goods. Last month it created a foreign exchange centre to serve importers of basic goods, such as industrial materials.

Already there are signs these official channels are being expanded. On Friday Iranian media reported the exchange centre would cover a wider variety of basic goods, such as olive oil. On Monday, state television quoted Industry Minister Mehdi Ghazanfari as saying the centre, now quoting a dollar rate of 25,550 rials, would begin providing hard currency to more categories of people requesting it, including students studying overseas and patients going abroad for medical treatment. “The exchange centre can soon take a lead role in determining currency prices in the free market,” he said.

It is not clear, though, whether the government will over the long term have enough hard currency to satisfy all demand through its official channels, especially if sanctions cut its exports far enough to push its trade balance into deficit. At the end of last year, Iran had official foreign reserves of $106 billion, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Their current level is a closely guarded secret, but some analysts estimate they may have dropped by several tens of billions of dollars as the sanctions cut Iran’s oil income.

As much as a third of the reserves may be trapped in banks overseas, where they cannot be used because of Western banking sanctions, some analysts believe.

Declining imports

Meanwhile, Iran’s merchandise imports are running at a rate of a little over $50 billion a year, according to the latest official data. Last year, export earnings outstripped import payments by $51 billion, but some analysts think sanctions may already nearly wipe that surplus out this year.

Nonetheless, figures for trade and reserves suggest the country does not risk running out of hard currency in the very near term, but that it could start to do so in the next year or two if sanctions continue.

The latest IMF World Economic Outlook released on Tuesday forecasts that it will maintain a small trade surplus this year and next, which would help it avoid a balance of payments crisis.

The risk could nevertheless prompt the government to ration dollar supplies tightly - providing hard currency to students travelling abroad if their discontent is politically troublesome, for example, but refusing to sell dollars to importers of luxuries, or to middle-class savers seeking to protect their assets from inflation.

And a state monopoly on foreign exchange would have other costs. The potential for corruption among officials handing out dollars is huge; Shabani said he had heard of people setting up bogus “export-import” firms in Iran just to obtain dollars.

“Depending on who you are and if you can get access to FX at a decent level, your cost structure will be totally different to others,” said Steve Hanke, economics professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “That means the economy is replete with distortions and as inflation picks up, they get worse.” Iran’s government may be content to accept such costs, however, if the system allows it to battle on against the West.

Emad Mostaque, a strategist at Religare Capital Markets, said the currency turmoil would be most damaging to the middle class and private merchants - but they were already not very politically supportive of the government.

People close to the government will be able to use official channels to get dollars, while the working class - 80 percent of the population - will not see its spending power fall too much as the government will provide subsidies, he wrote in a report.

“The current economic stress is nothing compared to 1988, where Iran halted the Iran-Iraq war with an economy in ruins following chemical weapons attacks, complete sanctions and oil at $10 per barrel,” Mostaque said. Oil is now above $100.