Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

By Harshanee Jayasekera and Dr. Nisha Arunatileka

Around the world, knowledge and innovation have become the drivers of global competitiveness. Countries are competing with each other to invest more on Research and Development (R&D) to help create more novel technologies to gain comparative advantages in knowledge. Workers in Science and Technology (S&T) are a key element of this. Towards understanding Sri Lanka’s development prospects from a human resource perspective, this article hopes to define and quantify the S&T human resources in the country and assess the quality of the S&T workers for their innovative potential.

Measuring HRST

Measuring the stock and flows of S&T human resources would give a clear picture about the innovative potential of an economy. This calls for a common and accepted measurement to both define this S&T workforce and to compare it across countries. One of the commonly accepted measurements is the Human Resources for Science and Technology (HRST), introduced by the Canberra Manual in 1995.

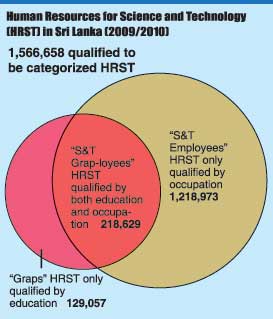

HRST is a broad definition encompassing those who are educationally qualified with tertiary education, those people working in S&T jobs, and those who are both educationally and occupationally qualified. For easy and memorable reference throughout this article, let each of these groups be referred to as “Graps” (in reference to them being graduates), “S&T employees”, and “S&T Grap-loyees”, respectively.

According to author’s calculations using available data, the count of HRST in Sri Lanka on average for the years 2009/2010 was 1.6 million people. Out of this, 218,629 were “S&T Grap-loyees,” while the number of “Graps” and “S&T employees” were 129,057 and 1,218,973 respectively.

Ideally, the larger HRST category in a country should be “S&T Grap-loyees” because it reflects the demand for S&T occupations filled in by persons with suitable skills. But, in Sri Lanka the HRST workforce is dominated by persons only qualified by occupation, i.e., “S&T employees”. The dominance of “S&T employees” indicates that either it is relatively easy for people with less-than-ideal qualifications to be employed in S&T occupations, or that better matching is necessary between education and occupational demands.

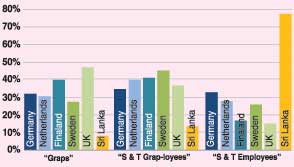

Benchmarking Sri Lanka

Compared to other countries, only a small percentage of “Graps” in Sri Lanka remained unemployed or employed in jobs for which they are overqualified. It is likely that these “graps” are queuing for government employment. However, given that most of the graduate output from state universities is in the fields of Arts and Humanities (nearly 60% in 2010[i]), the possibility of these “graps” actively contributing towards an innovative economy is, arguably, low.

For the most part, “S&T grap-loyees” are the drivers of innovation. A detailed look at the “S&T grap-loyees” in Sri Lanka shows that close to half of them are teaching professionals. The likelihood of these workers innovating is small (except, possibly, university academics).

Higher skilled workers are more likely to be able conduct research and development to create new technologies and to profit from existing know-how. The level of skills that often lead to innovation comes largely from higher education. Therefore it is important that more young people pursue degree qualifications in S&T fields of study.

In Sri Lanka, S&T undergraduate enrolment on average between 2008 and 2009 were 2 students per thousand populationiv. Comparatively, in India, it was 3 students per thousand population (2003), and in China it was 7 students per thousand population (2006). Compared to these dynamic emerging knowledge economies, Sri Lanka’s performance lags significantly behind.

Constraining Knowledge Economy

Capacity and resource constraints only allow a thin slice of the students graduating from general education to enter into state universities. Therefore, the growing demand for “S&T employees” capable of performing in occupations that demand higher levels of skills, will have to be sourced from people who have less than university level education. Even of the few that enter university, many study Arts which is not the kind of education suited towards building a strong S&T workforce which can engage in high end technological and knowledge creation activities. This is not ideal at all, especially for a country aiming to grow as a knowledge-based economy.

With the ever-growing human resource demand for S&T occupations, it is essential that more school leavers pursue university education. However, in enabling this, the almost entirely state-funded tertiary education system faces two main challenges – (1) increasing access to tertiary education, especially in S&T subjects, and (2) improving its quality. With more than half of youth between the ages of 20 – 24 not enrolled in any form of education, the former calls for more resources to sustain this inevitable growth of skilled labour demand, while the latter calls for a paradigm shift from Arts and Humanities to science education. (Courtesy Talking Economics)