Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

By G D Dayaratne

By G D Dayaratne

In Sri Lanka, Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) have existed unofficially for a long period. The first instance that such partnerships were seen in Sri Lanka’s health sector was during the shift in government policy in the post-1977 period of economic reforms, allowing medical practitioners from the government service to practice privately outside their official working hours.

There are around 17,000 government doctors working in government hospitals today. A majority of them consult privately as General Practitioners (GPs) or in private hospitals during their off-duty hours. A large number of full-time GPs from the private sector provide out-patient care at private clinics on a fee-for-service basis. Additionally, many private sector GPs also make referrals to government hospitals.

The flow of referrals occurs in both directions. In many government hospitals, doctors recommend that their patients obtain prescribed medical tests from private laboratories. The incidence of privately-conducted tests are so prevalent that most private hospitals in Colombo have set up laboratories and sample collection centres all across the country. Despite the cost involved in obtaining such a service, patients are often satisfied as they have confidence in the accuracy of the results.

However, while PPPs exist in an unofficial capacity of this nature, the Sri Lankan health sector remains distinctly a two tier system. The government provides free health care through a network of government health institutions, and the private sector engages in levying fees for the provision of services, arguably aimed at enhancing profit for investment.

PPP potential

PPPs are most useful in relation to patients suffering from acute illnesses – who are primarily being treated in government hospitals. This is especially poignant in light of the fact that Sri Lanka is confronted with a demographic shift towards an ageing population – a factor that is adding further pressure to the overburdened state health sector. Table 1 summarizes the current situation of the demand for health care in the country.

Increasingly the public health sector is finding it harder to cope with the rising demand for its services. This is made evident by the fact that as at present, over 5,000 patients are waiting heart surgery according to a recent announcement made by the government health authorities

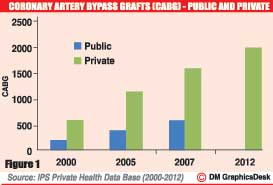

Figure 1 below, depicts the incidences of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafts (CABG) performed by public and private healthcare sector providers (data from the public sector is only available up to 2007). The Figure shows that Private Hospitals have improved their capacity of CABG intervention by 2½ times from 600 CABG in 2001 to 2000 in 2012 while public sector was lagging behind from 200 CABG in 2001 to 600 CABG in 2007.

According to the Private Hospitals Association, at any given time there are approximately 50 patients admitted as in-patients awaiting surgery. This is in addition to the monthly waiting lists of scheduled patients, the numbers of which might run well over 160. A fair number of these patients belong to the high risk category.

The situation described above clearly highlights the disparities in the capacities of the state and private sectors, despite being mostly served by the same medical personnel. The increased instances of CABG performed by private health providers indicate their improved capacity for intervention for a service mostly patronized by the upper and middle class segments from urban and suburban areas.

In this context, the private hospitals are at an advantage because administrators have embarked on the large scale introduction of new bio-medical technologies at a high cost, with the sole purpose of increasing their market share in a competitive health care delivery environment.

Public health authorities too, are taking steps to address the issues of capacity within government hospitals, with the proposed import of Bio-Medical Equipment (BME) at a cost of over Rs.2 billion . However, procurement of BME by the public hospital authorities will be subject to usual procedural delays, which will contribute to the already immense backlog of patients waiting for heart operations in government hospitals.

PPP as solution

An often unreported fact is that the government provides certain subsidies to private hospitals for the import of high tech BME. As a direct result, there is an abundance of medical equipment and technology available in metropolitan areas – particularly in Colombo city.

Therefore it is reasonable to expect the initiation of a feasible contractual arrangement with private hospitals in order to address the backlog of patients in the government system, until the proposed import of BME to government hospitals has materialized.

It is exceedingly important that the public dismisses the false notion that PPPs will lead to the privatization of the public health care delivery system. Public health authorities have a responsibility to reap the benefits from PPP arrangements, in order to reduce cost, share resources, provide quality assurance, and increase the efficiency of the healthcare delivery system without compromising on equity and fairness. Hence, institutional changes may be required in both the public and private sectors, to better fulfill their social mandate and provide quality health services to the people of the country.

.jpg)

(Talking Economics)

(The writer holds a BA from University of Peradeniya. He is currently Manager, Health Economic Policy Unit. He could be contacted via: [email protected])