Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

An architectural style often called Sri Lanka’s stamp on world architecture, It is Essential to be There is a never-seen-before insight into Bawa’s unique practice and style.

An architectural style often called Sri Lanka’s stamp on world architecture, It is Essential to be There is a never-seen-before insight into Bawa’s unique practice and style.

In Sri Lanka, it’s easy to spot a ‘Bawa Build’. Where most architects may find their signature style in uniformity, Bawa found his in the opposite; every design his own experiment with different styles of architecture in which no two builds are ever the same. All of Bawa’s builds, inclusive of some 35 hotels, houses, offices, schools and private properties, have come to define Sri Lanka’s architectural landscape in what architecture enthusiasts call ‘The Bawa Trail’.

All of Bawa’s builds, inclusive of some 35 hotels, houses, offices, schools and private properties, have come to define Sri Lanka’s architectural landscape in what architecture enthusiasts call ‘The Bawa Trail’.

My first real introduction to Bawa’s work was back in 2019 at the public opening of the newly rehomed Ena de Silva house at No. 5 Lunuganga. The house which was built back in 1960 by Bawa for his dear friend and batik artist Ena de Silva remained timelessly modern nearly 60 years later in a fashion that, despite the rapidly changing architectural landscape, seemed to never go out of style and likely, never will.

At the “Geoffrey Bawa: It is Essential to be There” exhibit, a model of this very house is presented next to a quote by Bawa; ‘The site gives the most powerful push to a design along with the brief. Without seeing the site, I cannot work. It is essential to be there. After two hours on the site, I have a mental picture of what will be there and how the site will change and the picture does not change.’

‘It is Essential to be There’ exhibition is on until April 3, 2022 at The Stables, Park Street Mews from 11 a.m to

7 p.m every day.

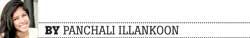

Throughout the exhibit, the notion of ‘being there’ is a common theme. Friends and family and archival letters framed at the exhibit will confirm of Bawa’s insistence on experiencing the site before any commitment was made. Exhibit Curator Shayari de Silva of the Geoffrey Bawa Trust adds that Bawa’s architecture is marked by multiplicities rather than categorizations, and that the qualities of ‘being there’ and the aspects of ‘place’ are central components of his work. When confronted with the notion of building for functionality and form, a hallmark of the architect’s style is the construction’s harmony with its natural setting – see in example the Ena de Silva house built in answer to Colombo’s contemporary city buzz, the House on the Red Cliffs in Mirissa that engages with the stunning cliff-top unimpeded by buildings or the Polontalawa Estate Building where he chose to build around, rather than remove, the existing rock boulders that were scattered across the site.

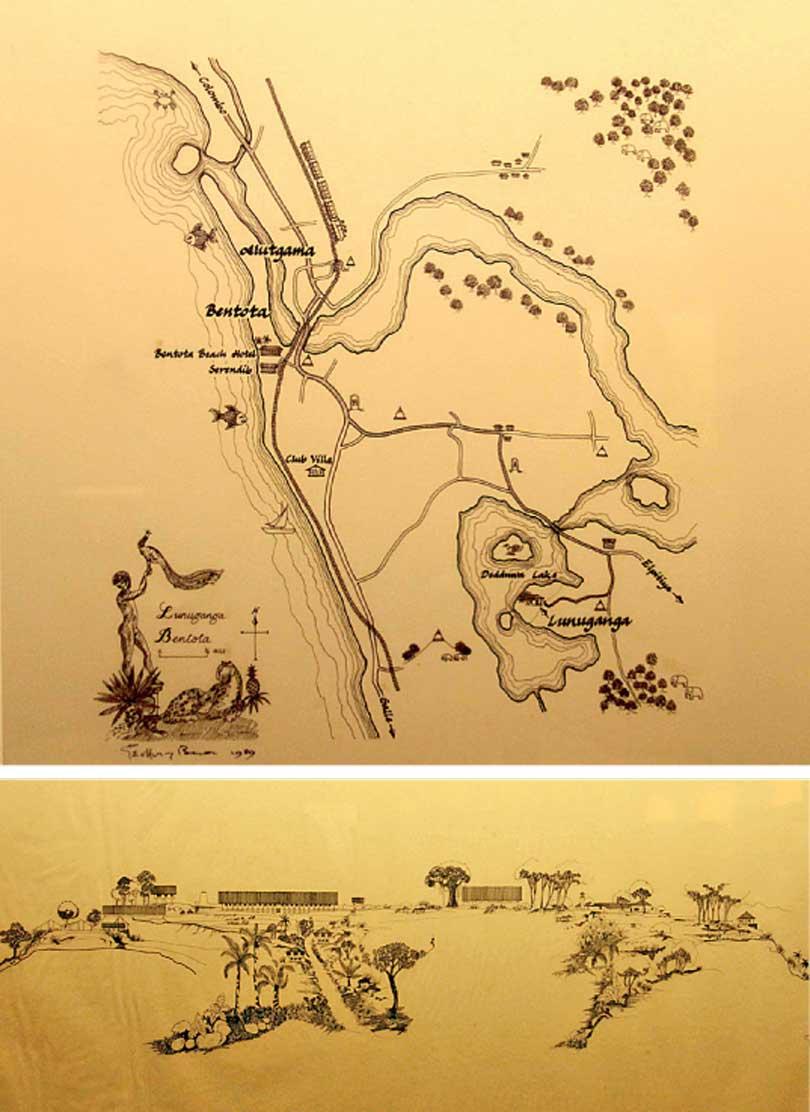

Though perhaps nothing speaks more volume of Bawa’s ability to meld nature and structure together than his most famous work with the Kandalama Hotel. The project at its initial stages was shrouded in controversy, galvanizing Sri Lanka’s environmental movement with major protests by activists given the environmentally and culturally sensitive location of Dambulla - the heart of the country’s cluster of ancient sacred kingdoms. Ultimately however, the hotel stands as a testament to Bawa’s talent for creating an architectural narrative where tourist facilities can be integrated into undeveloped, natural landscapes, balancing the need for appreciation of nature and natural beauty all the while protecting its location and environment. Interestingly, although it is undoubtably one of Sri Lanka’s most iconic architectural properties, Bawa was known to have remarked that this project would only be complete when it had turned into ruin, where the leopards may roam its corridors once more.

When we look beyond the focus of the concept of ‘place’, it is clear that Bawa’s architecture is also suffused with ideas about Sri Lanka. His work fused colonial and indigenous styles, incorporating materials such as local stone and timber in layouts of high roofs and vast overhangs, styled for cross-ventilation so specific to the country’s arid and monsoon climate.

When we look beyond the focus of the concept of ‘place’, it is clear that Bawa’s architecture is also suffused with ideas about Sri Lanka. His work fused colonial and indigenous styles, incorporating materials such as local stone and timber in layouts of high roofs and vast overhangs, styled for cross-ventilation so specific to the country’s arid and monsoon climate.

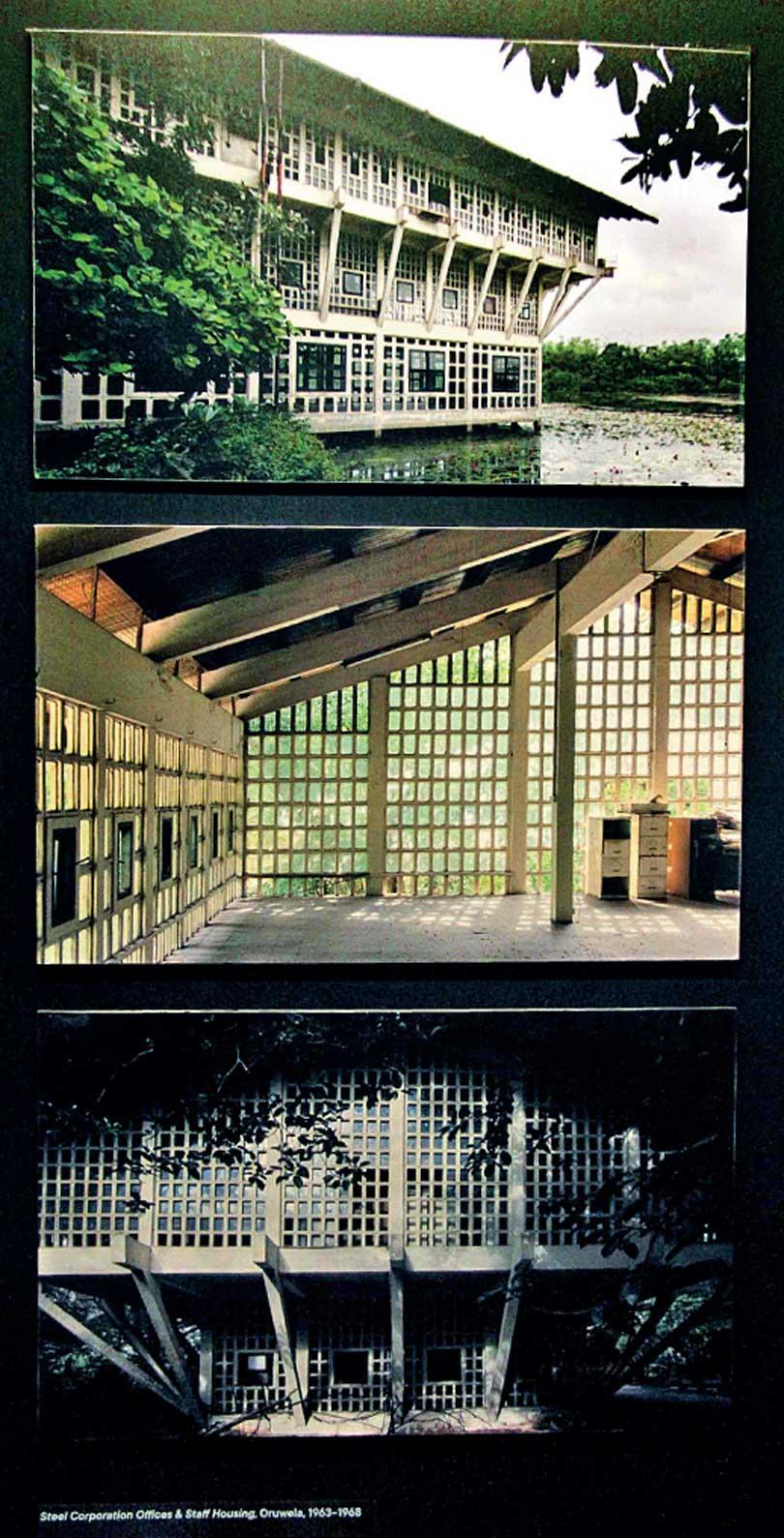

When Bawa formally began his architecture career as a partner at Edwards, Reid and Begg in 1957, though the practice was inspired with the possibilities for innovation in the Industrial Age, Sri Lanka’s closed economy measures that continued until 1977 forced Bawa and his associates to find alternatives with the limited materials available to express the forms and spaces they were conceiving of. This period saw the formation of Bawa’s bio climatically-responsive buildings; the introduction of a monitor roof at the St. Bridgets’ Montessori exploring how design could better serve the country’s warm and stuffy climate, a technique continued at Ladies’ College in the evolution of the overhanging balconies to offer shade to floors below and ventilation through classrooms and further refined in the remarkable roof-hung floor plate at the Bentota Beach Hotel and the State Mortgage Bank Building (now known as the Mahaweli Building) that traversed the ideas of a fully naturally ventilated office space.

The first exhibition of Bawa’s work to be shown in Sri Lanka, It is Essential to be There is an enthralling display and insight into the architectural mastermind that is Bawa. Organized in four thematic sections exploring the relationships between ideas, drawings, buildings and places with over 120 documents from the Bawa archives, most of which have never been shown publicly previously, it calls for retrospection and appreciation of the works that stamped Sri Lanka on the architecture map of the world. Organized by the Geoffrey Bawa Trust, the exhibition is open to the public free of charge.

Pics by Pradeep Dilrukshana