Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

“As an Asian writer, I’m glad that we have moved away from footnotes and long explanation notes at the end of our books explaining every cultural reference and that we now write on the basis that everyone somewhat understands the context of what we say.”

Does literature have to be relatable to everyone? In an age where 60% of the world’s population lives in Asia, three award-winning authors – Singaporean writer Balli Kaur Jaswal, Indian writer and journalist Manu Joseph and Sri Lanka’s very own Shehan Karunatilaka joined in a conversation about writing stories based in Asia in a world of fiction that still tends to cater towards Western readers.

Does literature have to be relatable to everyone? In an age where 60% of the world’s population lives in Asia, three award-winning authors – Singaporean writer Balli Kaur Jaswal, Indian writer and journalist Manu Joseph and Sri Lanka’s very own Shehan Karunatilaka joined in a conversation about writing stories based in Asia in a world of fiction that still tends to cater towards Western readers.

“When we write fiction, I don’t think everyone has to get the same context you did” answers Jaswal. “As an Asian writer, I’m glad that we have moved away from footnotes and long explanation notes at the end of our books explaining every cultural reference and that we now write on the basis that everyone somewhat understands the context of what we say.”

“When we write fiction, I don’t think everyone has to get the same context you did” answers Jaswal. “As an Asian writer, I’m glad that we have moved away from footnotes and long explanation notes at the end of our books explaining every cultural reference and that we now write on the basis that everyone somewhat understands the context of what we say.”

“To be honest, I have never thought about the global audience when I wrote” adds Karunatilaka. “My first book was about cricket and arrack and a left arm spinner at a cricket club and I genuinely didn’t think that anyone beyond the cricket club community would read it! Same with Maali. If you have to constantly think about the global audience when you write, then you will end up having to explain everything.”

“And really, when we say we want to make sure our work reaches “the global audience”, what we think and what we mean is that we want it to reach the West” interjects Manu Joseph, “and seeking that kind of validation, what does that really tell about us? I don’t think we want to know the answer to that.”

The discussion, wonderfully moderated by writer Thirangie Jayatilake, took the audience through an engaging discussion about how Asian literature has changed over the years as writers move away from restrictive stereotypical narratives (India and arranged marriages, Sri Lanka and the war, Singapore and the crazy, rich Asians) and the space Asian writers and their work occupies in the literary industry at present.

“Now, I can’t really say ‘who needs the West’ because I just got an award from the Queen of England,” concludes Karunatilaka inciting a roaring laugh from audience, “but I think we can say that we can write for ourselves now.”

Between Balli Kaur Jaswal’s humourous little anecdotes, Manu Joseph’s wry sense of humour and Shehan Karunatilaka’s easy personality, the session was easily one of the best events of the day.

A STAND-UP GUY:

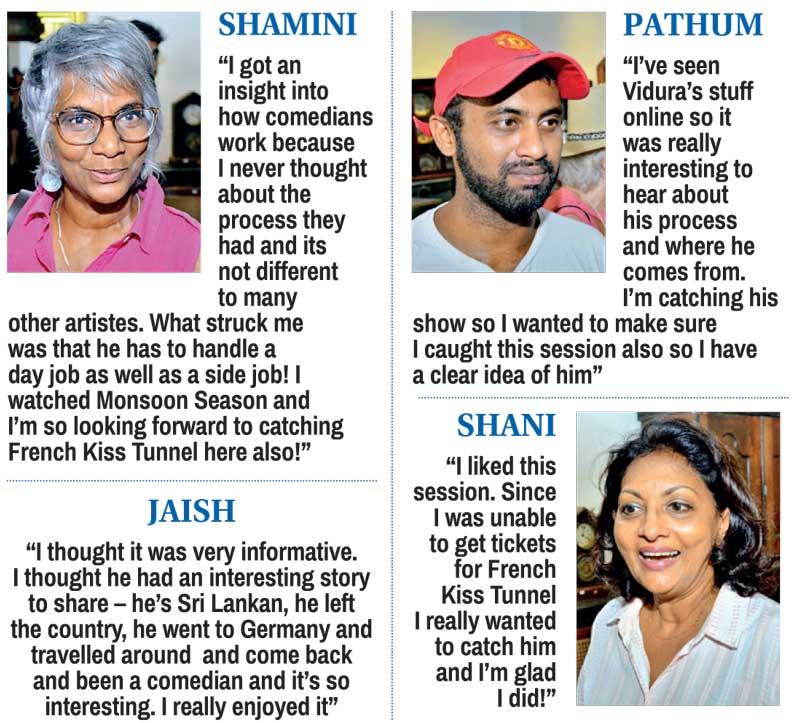

Vidura Br With Nicholas Brookes

Known for his dead-pan delivery and cutting quips (often at his own expense), Sri Lankan stand-up Vidura BR joined Nicholas Brookes, author of An Island’s Eleven for a conversation about writing, directing and making people laugh.

Vidura, who left Sri Lanka at a young age, attempted to follow a career in medicine by going to medical school in Malaysia before switching gears to software engineering in Berlin - a gig he still daylights in despite his budding career as a comedian. “Stand-up comedians are ironically just cranky professionals” tells Vidura to the audience, “but I’m tired now, I’m almost 30, my back hurts, I need my 8 hours of sleep so now is a great time for things to go well!”

Vidura’s debut show Monsoon Season which was picked for syndication on Amazon Prime Video received a ton of online attention and acclaim and was a big push towards the growth of his fame. As Brookes described the show as irreverent yet profound, personal yet global, Vidura condenses the same to ‘the greatest hits of my first five years’. “When I write my shows, I always put them through a series of tests – do I believe in the joke I’m saying, what’s the audience going to say and has it been done before?”

Vidura is currently on tour for his new show, French Kiss Tunnel, a preview performance of which was also on the Festival programme and sold out well before the Festival began.

How is the female body portrayed in art? Historian Mary Beard, dancer and poet Tishani Doshi and artist Fabienne Francotte joined together in a panel to deconstruct notions of gender and perceived beauty in a conversation about identity and our bodies.

How is the female body portrayed in art? Historian Mary Beard, dancer and poet Tishani Doshi and artist Fabienne Francotte joined together in a panel to deconstruct notions of gender and perceived beauty in a conversation about identity and our bodies.

At the start of the session, Britain’s best-known classicist and scholar of ancient Rome, Mary Beard displays an image to the audience – its goddess Aphrodite in the nude, reaching for a bath towel with one hand and the other loosely covering her genitals. The sculpture, Aphrodite of Knidos, was the first ever female nude sculpture in a long tradition of heroic male nudes – deeply controversial in its time in mid-fourth-century BCE but hugely revolutionary as it was the start of a long tradition of female nudes in Western art. It is also perhaps the visual start of what is commonly known as the ‘male gaze’ which the audience became increasingly aware of as Beard took them through a series of female sculptures and art over time – voyeuristic, and deeply eroticised.

In the East, writer and dancer Tishani Doshi displays the image of Lajja Gauri – a nude lotus-headed Hindu goddess from the 6th century with legs broadly spread-out, bent at the knees in the birthing position, often associated with abundance, fertility and sexuality. She maps her way to the Kamakhya Temple in North-East India, where Kamakhya Devi is known as the bleeding goddess. The sculpture, similar to that of Lajja Gauri with legs broadly spread out, inspires worship as many believe the goddess is a symbol of menstruation which in turn is seen as a symbol of a woman’s creativity and power to give birth. “What does it say to have an image of a fully nude goddess in a place of worship while women get told to cover up in order to worship it?” questioned Doshi.

It’s interesting to note how Beard’s history of the female body in western art juxtaposes with Doshi’s depiction of the female body in Asian art. While western art approached the female  body with a sense of eroticism and sensuality, Asian art was more singular and worshipful.

body with a sense of eroticism and sensuality, Asian art was more singular and worshipful.

So where does the female body place in the arts? Who occupies the space?

Contemporary artist Fabienne Francotte brings the audience back to the present, discussing at length the place of women artists in the art space. “As women artists, we all have to be Guerrilla Girls” she says, referring to the anonymous group of female artists advocating against the obvious sexism in the art world. The campaign illustrated that less than 5% of the artists in museums are women, but 85% of the nudes are female highlighting that both historically and, in the present, the arts have been and continues to be to a large extent, male dominated spaces.

Moderated by model and advocate, Kalpanee Gunawardana, the discussion between scholar, dancer and artist was incredibly informative and engaging.

Pix by Waruna

Wanniarachchi