Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Hiroshima after the bomb

August 6, 1945 remains to be a dark day in history. When ‘Little Boy’ made its way towards Hiroshima, immediately killing 80,000 odd people, people never imagined it to wipe away generations. They didn’t expect it to permanently deform their loved ones and contaminate their bodies with radiation. But that was reality. At 82, Ms. Keiko Ogura, one of the abled survivors of the attack and presently the director of Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace, claims that most news aired on media were fake. She claims that survivors had limited opportunities to share their stories and was delighted to speak to the Daily Mirror, during a recent visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

August 6, 1945 remains to be a dark day in history. When ‘Little Boy’ made its way towards Hiroshima, immediately killing 80,000 odd people, people never imagined it to wipe away generations. They didn’t expect it to permanently deform their loved ones and contaminate their bodies with radiation. But that was reality. At 82, Ms. Keiko Ogura, one of the abled survivors of the attack and presently the director of Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace, claims that most news aired on media were fake. She claims that survivors had limited opportunities to share their stories and was delighted to speak to the Daily Mirror, during a recent visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

70 years ago

“That day I didn’t go to school because my father had an instinct that something bad would happen,” recalled Ms. Ogura. “The previous night was quite strange. All of a sudden there was an air raid warning and we rushed to the shelter. We waited but nothing happened. We tried to sleep and 30 minutes later there was another warning. Then another. Likewise there were unusual warnings and as a result I didn’t go to school. At first there was a blinding flash and instantly flammable things caught fire. This was followed by a blast which I thought was a tornado. Seconds later I was lying unconscious on the ground. When I came to my senses, I saw people fleeing with burning clothes and many of them were naked. At one point they were walking like zombies because their skin was peeling off and faces were swollen. When I opened my eyes everywhere was dark and I thought it was evening. All the burning buildings were crushed down and that whole night the city kept burning and there was nothing left the next morning. People developed serious diseases and we did not know that most of them were caused by radiation. The next day my father cremated over 700 people.”

“Dead bodies were floating in all rivers to faraway places,” she continued. “People were asked to go to temples in case something happened and that there would be first aid stations. In front of my house there was a road that led up to a Shinto shrine and people started coming because they thought there may be a doctor. But there was only one soldier with a bucket of oil to apply on the wounds of the injured. I was astonished that the roofs were scattered and my neighbourhood houses were damaged. There were pieces of glasses stuck on the walls. I stepped out and the black rain started. I couldn’t understand what it was and we didn’t know that it was dangerous. People rushed to my area but I refused to give water because during the war we learned that we shouldn’t give water to people because they would die. People were exhausted and thirsty and they tried drinking water from the black rain.”

According to her, many people have reached her home asking for water. “Then I gave water and two of them died in front of me. That added to my trauma and started to blame myself. For almost 10 years I saw nightmares. There were many people who suffered and many survivors blamed themselves.People were dying everyday. Even before the bombings I used to be very scared of airplanes and that too added to my trauma. When I went to Washington D.C for the first time, I saw small airplanes at the Smithsonian and started to tremble and cry.”

Survival instincts

Ms. Ogura says that soon after the bomb, around 60,000 bodies were found. “Everyday I saw small fires lit to cremate people, coming out of everywhere, and even my father was cremating bodies. A few months before the bombing we were living around the hypocentre but my father said we need to move since other cities were being attacked and the next would be Hiroshima. But I did not want to go because I loved going to school. Since we moved, I was able to survive. My neighbours and classmates died. My new home was 2.5km from the Hiroshima train station. Because it was further away from the hypocentre my house wasn’t burned down. Rivers were full of people, some living, some dead. Many people fled the city and came towards the hills.”

Many generations lost

“There were many survivors at the time and I thought education and media were important,” she opined. “But the media exaggerated it to an extent that most news were fake. So I wanted to educate the masses about what ordinary people like me were doing. At the height of the war, there were tiny pieces of paper with Japanese words scattered from US airplanes and we were asked not to collect them. If anybody was found with them they were considered as spies. So we were told to submit those papers to the Police. At schools, Japanese Military approached English teachers and questioned them as to whether they were spies. During the war time, junior high school students from 13-15 years were mobilized and forced to work in the centre part of the city. They couldn’t do skillful work but were asked to demolished houses. Most of the time students didn’t have time to study. Therefore 70% of students in the city died immediately after the bomb. Education was bad, the media was telling the wrong thing. Even after the city was destroyed other cities weren’t told the impact of the bomb. The military tried to hide it. We didn’t know that it was a nuclear weapon but everybody was told that it was a new weapon. The city was filled with radiation but by that time many people entered the city to help their family members. But they were contaminated by radiation. Soon after, many people died without any scars on them. But their hair started to fall, gums started to bleed, black spots appeared and then we knew that a person was dying.”

The former Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall now preserved and stands as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial or the A-Bomb Dome

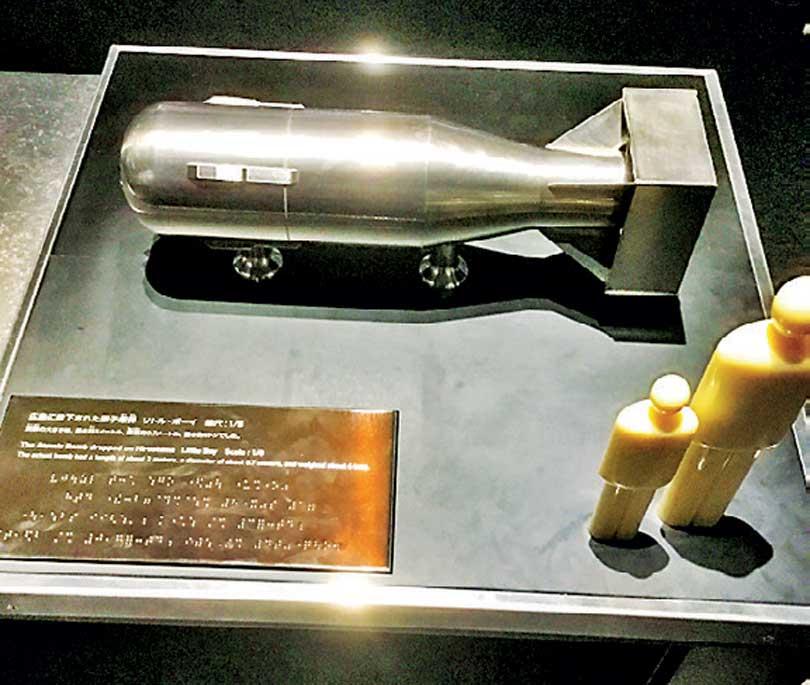

Replica of Little Boy

Memorial cenotaph at the Park

Belongings of children who passed away

Hiroshima before the bomb in 1945

Living with stigma

Stigma and discrimination have been barriers for the most part of their lives. “People from Hiroshima or Nagasaki didn’t want to tell where they were from because soon after the bombing there was a rumour that it was better not to get married with someone in the city,” she recalled. “Most of my friends couldn’t get married while some of their fiancés left. We stopped talking about what happened to us. Even my sisters living outside Tokyo kept quiet. Some parents worried about discrimination. They waited until their daughters or sons got married or till they delivered healthy babies to say that they were survivors. Then they asked for a certificate but they needed two witnesses to verify that they were there in the city. Case workers helped to find out witnesses. I myself felt people ill-speaking about me as well. My classmates were discriminated against and one of them told me that her fiancé left. But my brother got married to one of my friends and he did evacuation and later he returned home. Survivors tried getting married to survivors. But we had a strong fear whether we could have babies. Some survivors couldn’t have babies. There were babies with multiple fingers, some were born dead and some were miscarried. The Japanese do not speak out. Some babies had microcephaly and we tried to hide. We wanted to find out if my babies were healthy. I interviewed many survivors but they asked me not to come into the house. They related their stories outside their houses. People didn’t want their children to be asked about the incident. Parents didn’t tell what happened. We did not complain. 10 years later the first international conference against nuclear weapons was held in Hiroshima. It was a big leap. Until that time we shut our mouths and tried not to talk about the incident. At the time, one brave survivor stood out and told what happened. Till then we thought we were unlucky people but the world understood how cruel a nuclear weapon could be.”

Stigma and discrimination have been barriers for the most part of their lives. “People from Hiroshima or Nagasaki didn’t want to tell where they were from because soon after the bombing there was a rumour that it was better not to get married with someone in the city,” she recalled. “Most of my friends couldn’t get married while some of their fiancés left. We stopped talking about what happened to us. Even my sisters living outside Tokyo kept quiet. Some parents worried about discrimination. They waited until their daughters or sons got married or till they delivered healthy babies to say that they were survivors. Then they asked for a certificate but they needed two witnesses to verify that they were there in the city. Case workers helped to find out witnesses. I myself felt people ill-speaking about me as well. My classmates were discriminated against and one of them told me that her fiancé left. But my brother got married to one of my friends and he did evacuation and later he returned home. Survivors tried getting married to survivors. But we had a strong fear whether we could have babies. Some survivors couldn’t have babies. There were babies with multiple fingers, some were born dead and some were miscarried. The Japanese do not speak out. Some babies had microcephaly and we tried to hide. We wanted to find out if my babies were healthy. I interviewed many survivors but they asked me not to come into the house. They related their stories outside their houses. People didn’t want their children to be asked about the incident. Parents didn’t tell what happened. We did not complain. 10 years later the first international conference against nuclear weapons was held in Hiroshima. It was a big leap. Until that time we shut our mouths and tried not to talk about the incident. At the time, one brave survivor stood out and told what happened. Till then we thought we were unlucky people but the world understood how cruel a nuclear weapon could be.”

Through a special bill that was passed, the people of Hiroshima started to work, spending sleepless nights with an aim to rebuild the city. 12 years later, it began to stand on its own. Street cars started to move and electricity was restored. 70 years later, the hypocentre has been transformed into a peace memorial park while the main memorial stands in the backdrop of an eternal flame which will be put out once all nuclear weapons in the world have been destroyed. Ms. Ogura says that the ordinary American citizen should not be blamed. Today, while people of Hiroshima still await an official apology from the US, Hiroshima is already home to many American pubs and restaurant chains, sending out a strong message to the rest of the world that coexistence is possible.