Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

A week before the 2019 presidential polls, a 55-page report on Sri Lanka’s kidney disease epidemic was distributed to all 35 candidates. None responded to the hard-hitting findings. With a new government now in power, the jury is still out on who will take action—and when—on this critical issue.

Compiled by Dr. Kamal Gammampila, an independent researcher who has spent over six years studying the crisis, the report argues that the term most commonly used to describe the problem—Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Etiology, or CKDU—is a misnomer. Far from being unknown, he claims the cause of the crisis is very clear: toxic rice.

Thus far much of the scholarship concerning CKDU has focused on contaminated drinking water caused by the excessive use of fertilizers, weedicides and pesticides containing heavy metals like cadmium, arsenic, lead and glyphosate. But this, according to his research, is only partly true. Entitled ‘A Threat to Our Existence’, the report suggests that consumption of metal-laden water alone is not sufficient to create an epidemic of the scale we are witnessing in Sri Lanka today, where an estimated 400,000 people are affected by kidney disease. He believes the root cause is the use of contaminated water in paddy cultivation.

Thus far much of the scholarship concerning CKDU has focused on contaminated drinking water caused by the excessive use of fertilizers, weedicides and pesticides containing heavy metals like cadmium, arsenic, lead and glyphosate. But this, according to his research, is only partly true. Entitled ‘A Threat to Our Existence’, the report suggests that consumption of metal-laden water alone is not sufficient to create an epidemic of the scale we are witnessing in Sri Lanka today, where an estimated 400,000 people are affected by kidney disease. He believes the root cause is the use of contaminated water in paddy cultivation.

A single kg of rice requires 3,000-5,000 litres of water to produce—what the researcher calls the “rice-water footprint”. Through a process known as biomagnification, dangerous heavy metals thus become concentrated in the rice grain via the water source. Considering that the average Sri Lankan consumes about 120kg of rice annually, we are confronted with a situation where an ancient, staple diet is daily poisoning large swathes of the population in the North Central Province (NCP), and trickling into every household in the country that relies on rice grown in the Rajarata region. Currently, 65% of our national rice needs are met by farmers living in CKDU-affected areas.

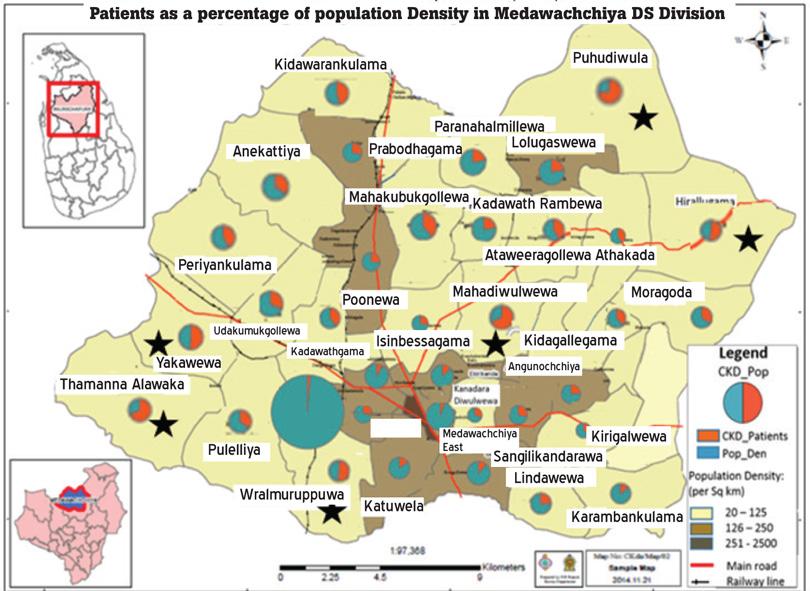

Metal-contaminated water originates in the hill country, where chemical runoff from large scale agricultural operations including tea plantations has entered the Mahaweli River, the main water source for a majority of paddy farmers in the Dry Zone. Contaminants from the hill country have also entered reservoirs, canals and a network of interconnected waterways that feed paddy fields in the NCP. Citing a study conducted by the Presidential Task Force on Chronic Kidney Disease Prevention, the report notes: “CKDU is present in all regions where hill country water is used for rice cultivation”. For instance in 25% of the Grama Niladhari Divisions across the Madawachchiya District, the majority of the population have been identified as kidney patients since about 2015.

On the flip side, regions that are considered “CKDU-free”—such as the West Coast, Jaffna and parts of the East Coast including Ampara—are areas that do not receive hill country water for paddy cultivation, relying instead on rainwater, forest reservations, or local mountains. The report cites the example of the Senanayake Samudraya, a 90-square-km reservoir inAmpara which serves as the principle agricultural water source for the region and is protected from hill country water by the mountain ranges of Dehigolla and Udakiruwa. Incidence of CKDU in this region is virtually non-existent. Similarly, communities in Kadugama in Mihintale who practice rainwater paddy cultivation are considered CKDU-free, while the population in the nearby 6,000-acre paddy area relying on water from the contaminated Mahakandarawa Wewa reports a 20% incidence of CKDU, or cancer, or both.

According to a study conducted by Dr. Gammampila in 2018,CKDU status is sometimes determined by a matter of a few km, as is the case in some parts of the Central Province. Here, farming communities using chemical-free water from the Heen Ganga, originating in the Knuckles Mountain Range, are completely CKDU-free, whereas their neighbors who rely on the hill country-fed Minipe Canal report significant numbers of kidney patients. In some cases, siblings living in the same village, drinking the same water, have different CKDU status—the only variable being the water source used to cultivate their respective paddy lands. Since the rice plant takes up only about one percent of available heavy metals, the remainder of metals from hill country water have, over the years, made the soil in these regions unsuitable for rice cultivation.

If these findings are accurate, the implications of the report are monumental. It demands nothing short of an overhaul of the farming and irrigation system throughout the NCP, which is the beating heart of our national agricultural system, the nucleus of an ancient civilization, and home to one of Sri Lanka’s most lucrative tourist attractions.

Dr. Gammampila estimates a 20-25 year recovery period for the region, during which time thousands of acres of ruined paddy lands will have to be revived , and an alternative water source identified, as the Mahaweli has been reduced to what he terms a “spent” water source or, put simply, a drain.

From a humanitarian perspective, urgent action is required on behalf of “endangered and annihilated communities”, populations that have, and will, continue to consume such highly toxic rice on a daily basis that they are at risk of being wiped out. In 20 years, he estimates half a million people, or 2% of our population, would have been dead from kidney failure, or other associated ailments. Citing statistics from UNICEF and the World Food Programme (WFP), Dr. Gammampila points to deteriorating nutrition rates across the island as indicative of the widespread impacts of lead and cadmium in rice—including a 16% incidence of “wasting” in children, acute malnutrition rates ranging from 14-35% across 25 districts, and the fact that Sri Lanka now has the highest number of oral cancer patients in the world according to the Faculty of Dental Science at the Peradeniya University.

Local academics must stop feeding the international community with “bogus data” and get serious about addressing the unfolding tragedy

-Dr. Gammampila

Since pregnant women, breast-feeding mothers, newborns and young children are considered a high-risk group for lead exposure, which the WHO has linked to kidney disease and a range of other neurological and physical development issues, the report advocates immediate action on their behalf, including United Nations intervention as well as technical assistance from WFP and FAO.

“It doesn’t matter who is in power or who runs the country,” he told a recent interview with Ecosocialist Horizons, a global non-profit organization. “No one is guilty but everyone is responsible.” In this regard he named a range of parties, from politicians to the fertilizer lobby, and from international agencies to the academic, medical and scientific communities—all of whom, he believes, are aware of the cause of the crisis but refuse to confront it. His report identifies a fleet of recent scientific studies that fail to acknowledge the link between hill country water in paddy cultivation and kidney disease. He also criticizes the authors of a number of newspaper articles who suggest that farmers themselves are to blame for their sickness, for over-applying fertilizer to their paddy lands.

Careless scholarship on the issue, he argues, has repercussions beyond our national borders. CKDU is increasingly being recognized as a global epidemic, with several countries in Central America experiencing what scientists are calling a “silent massacre”. In the past two decades the disease has claimed 20,000 lives in the region. Nicaragua and El Salvador have been the hardest hit. In 2009, CKDU was the second most common cause of death for Salvadoran males. In 2017, it accounted for about 75% of deaths among young and middle-aged men in Nicaragua. Significantly, the epidemic is worst among daily laborers on sugarcane plantations, which, similar to Sri Lanka’s tea estates and paddy lands, require huge inputs of fertilizer. And while Dr. Gammampila is reluctant to draw direct links between the two regions, he believes Sri Lanka could serve as a case study for a worldwide health burden. To this end, he urges local academics to stop feeding the international community with “bogus data” and get serious about addressing the unfolding tragedy.