Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

“Widely acknowledged as the largest leopard sub-species, the Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) is seen here with the kill of a wild pig in Tandoureh National Park, Kopetdag mountains, Iran-Turkmenistan border (Farhadinia et al. 2022, Status of Persian leopards in northern Iran and Central Asia, CATNews 15)”

“The Leopard - An Ideal Conservation Umbrella” is the second article in a series focusing on the leopard’s conservation efforts. The Indian leopard, classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN, faces challenges due to human-leopard co-existence, with increasing contact leading to human-wildlife conflicts. Surprisingly, some urban and rural areas in India exhibit remarkable peaceful co-existence with leopards. In Jaipur’s Jhalana Forest reserve, where the Jain population respects all living beings, up to 40 leopards thrive alongside humans without conflict. Similarly, in the Gir forests of Gujarat, Asia’s only remaining wild lion population coexists with a high density of leopards. This article explores the complex dynamics of human-carnivore interactions and their impact on conservation efforts for the Indian and Persian leopard

sub-species.

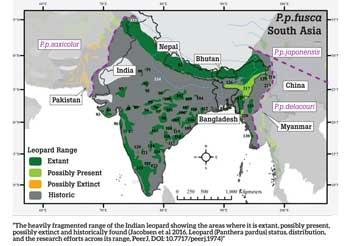

The Indian leopard

(Pantherapardusfusca) – IUCN Status: Vulnerable. Estimate range loss (2016): 72%

Considering that India is going to overtake China very soon as the world’s most populous nation – at just over 1/3 of China’s physical size! - it is no surprise that the key issue in India about leopard conservation is human-leopard co-existence. An estimated 12,000 - 14,000 leopards live in India according to government reports and, partially due to the presence of tigers (Panthera Tigris) which can push them out of their prime habitat, they come into increasing contact with humans, with roughly 500 leopards killed annually as a result.

Despite this, there are amazing cases of largely peaceful co-existence. The leopard’s that inhabit Mumbai’s Sanjay Gandhi National Park are perhaps the most celebrated of these due to various films and documentaries about them, and while this scenario is indeed remarkable, it is perhaps less so found to the north in Rajasthan’s, Jaipur. Here, in the 29 km2Jhalana Forest reserve, which like Sanjay Gandhi NP is surrounded by a teeming metropolis (of 3.95 million compared to Mumbai’s 12.5 million), it is estimated that up to 40 leopards live with apparently no conflict with humans. A major reason for this is that most of the people that live here – mostly low-income, uneducated and unskilled labourers - are followers of Jainism, a religion under which all living things are sacrosanct and harming them is considered essentially taboo. In this remarkable place, 67% of people interviewed said that they encounter leopards daily. Unlike in Mumbai, where the leopards are in very close proximity, but careful to remain hidden, in Jaipur it is not unusual for a female leopard to call her tiny cubs to the forest edge to drink at one of the numerous concrete water bowls in front of the admiring eyes of a bustling street front. As in Mumbai, dogs are an integral part of the leopard’s diet in Jaipur, supplemented by cow carcasses (the Jain diet allows for the consumption of dairy products) which here are purposefully left in the forest for the leopards to scavenge. Some fascinating research is attempting to quantify the ecosystem and social benefits of these behaviours and suggests that Jaipur has by far the lowest incidents of dog bites of any major Indian city, with an attendant reduction in rabies cases. The effect of leopards scavenging on cows that have died, in terms of disease mitigation, is also seen as a positive benefit.

In rural Maharashtra State, leopards live in completely agricultural landscapes where almost 100% of their diet consists of domestic species. Here, and in other areas of India,

compensation schemes appear to work well, with villagers able to partially offset their economic losses from livestock depredation. Key to both the urban and rural scenarios are the attitudes of people as it is only by accepting shared spaces and some losses that these kinds of co-existence paradigms can be sustainable. These areas make us question the notion of what constitutes wilderness as wild animals do not necessarily need to live in what are classically viewed as “wild spaces”.

Many of the Indian presentations at the GLC came from the Gir forests of Gujarat – home to Asia’s only remaining wild population of lions. This human-lion nexus is another quite remarkable example of human-carnivore co-existence but it is the sharing of space between lions and leopards here that was the focus of much of this work presented at the GLC. Research showed a very high density of leopards in Gir (19.9/100 km2) with lion numbers almost as high (15/100 km2) in what is surely one of the world’s most felid-rich systems. Interestingly, both big cats seem to be sharing resources – often cattle, but also sambar - with dietary overlap increasing over time to the point that there is almost total overlap now. The age and sex classes of prey were not assessed and it may be that utilizing different classes (e.g. lions taking adults and leopards’ calves/fawns) is what allows for the observed co-existence. Another fascinating insight came from a study tracking a female leopard outside the Gir Sanctuary which showed that this female spent 80% of her time within 50m of humans – but didn’t have negative interactions with anyone.

Many of the Indian presentations at the GLC came from the Gir forests of Gujarat – home to Asia’s only remaining wild population of lions. This human-lion nexus is another quite remarkable example of human-carnivore co-existence but it is the sharing of space between lions and leopards here that was the focus of much of this work presented at the GLC. Research showed a very high density of leopards in Gir (19.9/100 km2) with lion numbers almost as high (15/100 km2) in what is surely one of the world’s most felid-rich systems. Interestingly, both big cats seem to be sharing resources – often cattle, but also sambar - with dietary overlap increasing over time to the point that there is almost total overlap now. The age and sex classes of prey were not assessed and it may be that utilizing different classes (e.g. lions taking adults and leopards’ calves/fawns) is what allows for the observed co-existence. Another fascinating insight came from a study tracking a female leopard outside the Gir Sanctuary which showed that this female spent 80% of her time within 50m of humans – but didn’t have negative interactions with anyone.

The Indian leopard is also a sub-species found in Nepal, Bhutan, northern Pakistan and

western Myanmar.

The Persian leopard

(Pantherapardussaxicolor/tulliana) – IUCN Status: Endangered. Estimated range loss (2016): 84%

Widely acknowledged to be the largest of the leopard sub-species, the Persian leopard is mostly found in Iran, but with small populations spilling over into neighbouring countries including northern Iraq, southwestern Turkmenistan, south-eastern Turkey, Afghanistan and possibly western Pakistan. A fragmented population also exists in the borderlands between Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Russia. A lot of research effort has been expended on understanding the status of the Persian leopard, as well as its potential prey base and movement patterns, and there is a nationally backed conservation plan which aims to ensure its long-term survival. Trans-border issues are key, with its range crossing sometimes contentious borders (e.g. Armenia/Azerbaijan). Another key issue for this sub-species is resolving conflict with humans over livestock, as several Persian leopards are killed annually in reprisal for predating goats, sheep and cattle. As with the Arabian and Amur leopards, there are ongoing captive breeding efforts for the Persian leopard with 25 captive-born individuals being prepared for re-introduction in the coming years.

© Kittle & Watson, WWCT.org (2023), Wilderness & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Si Lanka. All work by WWCT is conducted under the purview of and often in collaboration with the Department of Wildlife Conservation, Sri Lanka.