Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

The Covid pandemic has not just affected the health of the people in the country; but also the jobs and its economy. Here is a take on covid’s impact on technical education and related vocations

Technical and vocational graduates from tourism and hospitality courses or graduates working as self-employed were the hardest hit.

The expectation that online learning could continue during the pandemic was high, although only one in five households owned either a desktop or laptop in Sri Lanka

Quality of learning could be improved significantly through financial support to students

A report by the Asian Development Bank highlights how Sri Lanka’s ambitious goals for technical education declined in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. The peer-reviewed study presents evidence of the impact of the pandemic on Technical and Vocational Education and Training. The institutions have made efforts to initiate or expand online training delivery during the pandemic but face many challenges, the study shows.

education declined in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. The peer-reviewed study presents evidence of the impact of the pandemic on Technical and Vocational Education and Training. The institutions have made efforts to initiate or expand online training delivery during the pandemic but face many challenges, the study shows.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa declared 2021–2030 as the “Decade of Skills Development”, which has the ambitious goal of reducing the population of unskilled labour to 10%. This is in line with the national development policy framework “Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour” Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) will play an instrumental role to realise this goal. After the parliamentary elections in August 2020, the government strengthened institutional arrangements by integrating responsibility for TVET into the Ministry of Education so that all education subsectors (general education, skills development, and higher education) could be holistically geared toward skills development to meet the fast-changing demands of the fourth industrial revolution.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has posed significant challenges to education and employment, including TVET. Current TVET instructors and students have struggled with online and distance education, which was introduced abruptly under the new norm of social distancing. TVET institutions experienced the significant challenge of providing hands-on practical training using tools and machines through online training. The turbulence in Sri Lanka’s job market created by COVID-19 will have a negative impact on the employment outcomes of TVET graduates, the report found.

COVID-19 IMPACT ON LABOuR MARKET

Sri Lanka managed to keep the number of COVID-19 cases relatively low until September 2020, but the economic contraction was unavoidable. COVID-19 dealt a significant blow to the economy, which was projected to contract by 5.5% in 2020.

A resurgence of COVID-19 cases from the fourth quarter of 2020 caused economic uncertainties for 2021, especially for exports and tourism. The effects of the economic downturn that began after the Easter Sunday attacks in April 2019 when gross domestic product fell to 2.3% in 2019 from 3%–5% during 2014–2018 are still lingering.

In Sri Lanka, the first positive case of COVID-19 was identified on 27 January 2020 in a foreign tourist. Positive cases were found among Sri Lankan nationals from early March 2020.

The government declared public holidays to contain the spread of the virus and a lockdown-styled curfew was in place from 20 March to 11 May 2020, although some parts of the country lifted the curfew earlier than 11 May 2020. All the education and training institutions were closed beginning March 2020. They gradually reopened from June 2020, but the second wave of outbreak started in October 2020 and a partial lockdown was again imposed in high-risk areas.

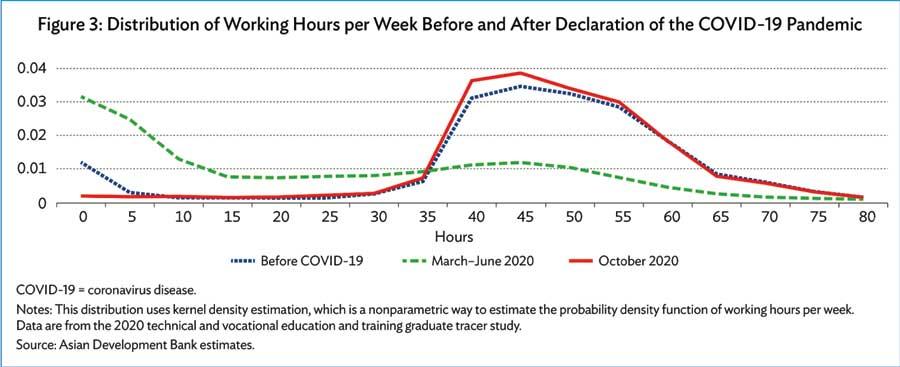

Compared to the same months in 2019, online job postings dropped significantly during the first two waves of COVID-19 in 2020.

The number of online job postings had declined sharply from March 2020, especially for the tourism and hospitality sector, but gradually improved by September 2020. It again declined significantly when the second wave began in October 2020. While the number of COVID-19 cases grew rapidly in 2020 the number of online postings began to recover in December. This recovery may not signal additional employment if the online job advertisement is to replace the jobs lost during the first wave, or if more employers use online job posting as a means of recruiting employees.

Labour demand remained weak for tourism and hospitality from the start of the pandemic in March 2020. This is because of the international travel restrictions due to COVID-19 although international tourists started to visit Sri Lanka from the end of December 2020 on a pilot programme basis.

Under the government’s medium-term Skills Sector Development Programme 2014–2020, four industries were prioritised: (i) building and construction, (ii) tourism and hospitality, (iii) metal and light engineering, and (iv) information and communication technology (ICT). Except for the tourism and hospitality sector, the priority industries showed resilience to this shock compared to the overall average. Engineering-related online postings recovered quickly after the first wave. During the second wave, postings for information technology recovered strongly.

Education and training

COVID-19 forced students to continue their education and training online, a learning approach that is not completely new to the TVET sector in Sri Lanka. Before COVID-19, only 36% of TVET institutions provided distance learning.

The use of online platforms for delivering training accelerated during the pandemic. Online offerings are important in mitigating the risk of COVID-19 transmission, and TVEC has facilitated open access to e-resources during the pandemic. Besides, while TVET institutions resumed face-to-face training in June 2020, some institutions remained closed due to the partial lockdown and still continue to rely on online technologies.

The expectation that TVET could continue during the pandemic was high, although only one in five households owned either a desktop or laptop in Sri Lanka (Government of Sri Lanka 2019).

The Findings: COVID-19 Impact on Employment

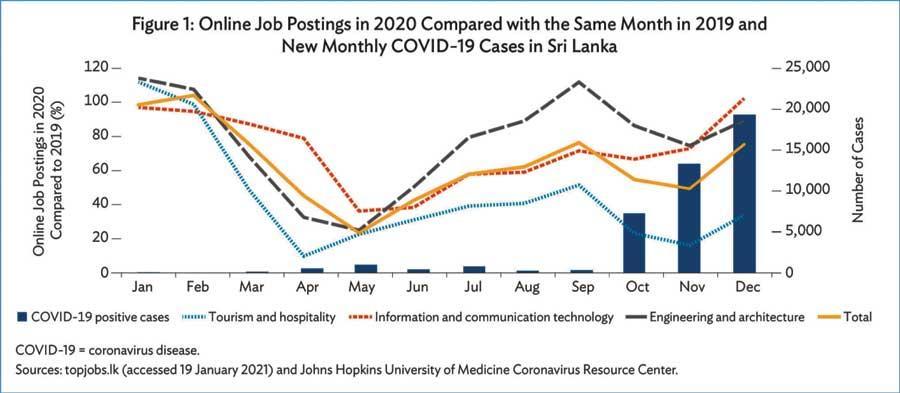

The job placement rate dropped by 2.8 percentage points from 51.0% in 2019 to 48.2% in 2020. The decline is driven by graduates who took TVET courses not certified under the National Vocational Qualification framework. The decline in employed TVET graduates is also evident in Figure 2.

Interestingly, TVET graduates started to leave their jobs a few months before the pandemic began because of the timing of the new courses (starting in January 2020).

However, the number of TVET graduates who were forced into unemployment hiked after the pandemic was declared in March 2020. There is a strong gender impact, as shown by the significant decline among male non-national vocational qualification graduates. Besides, among the unemployed job seekers as of November 2020, one third mentioned that COVID-19 forced them to look for a job.

However, the decline in job placement rate started even before COVID-19 as the figure in 2019 was 51.0%, which was lower than 54.5% in 2016 (Table 1 expectation that TVET could continue during the pandemic was high, although only one in five households owned either a desktop or laptop in Sri Lanka).

In contrast, the employment rate improved slightly from 70.3% in 2019 to 70.8% in 2020 due to a drop in labour force participation by TVET graduates.

The employment rate is calculated as the number of currently employed graduates divided by the graduates in the labour force. The graduates outside the labour force are mostly students, and COVID-19 might have prompted students, especially women, to continue in education and training rather than enter the labour force.

Moreover, while some graduates continued to look for jobs online, by phone, and through social networks, others stopped looking for jobs due to the reduced number of job postings and health concerns around COVID-19. By sector, tourism and hospitality were significantly affected, as the employment rate declined from 76.6% in 2019 to 58.9% in 2020.

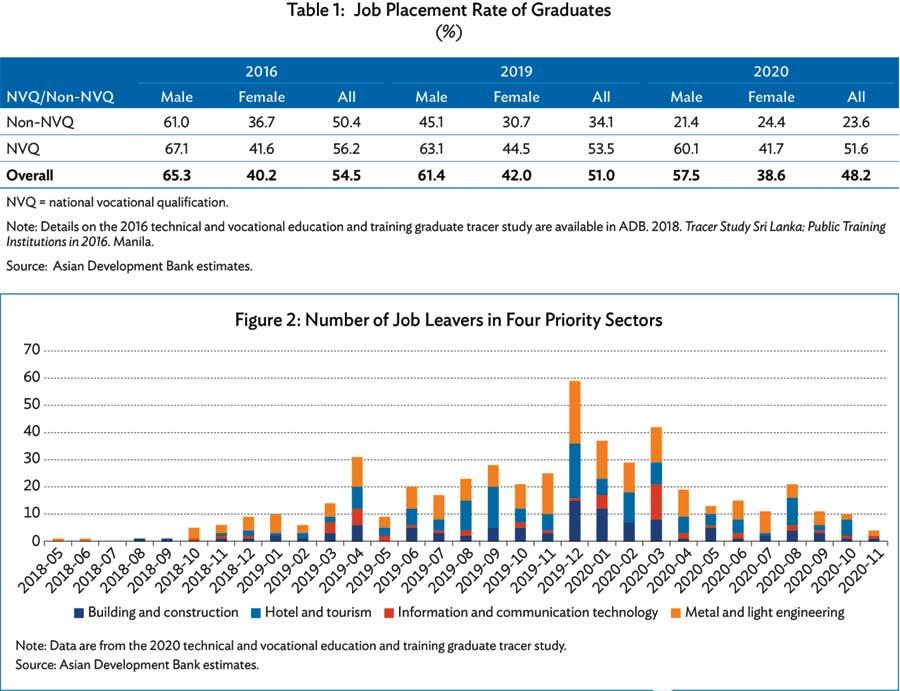

COVID-19 Impact on Working Hours

The immediate COVID-19 impact was a reduction in working hours. Figure 3 shows weekly working hours among TVET graduates (i) before COVID-19 (before March 2020), (ii) during the first wave of COVID-19 (March–June 2020), and (iii) during the second wave of COVID-19 (November 2020). During the first wave, most TVET graduates worked less than 5 hours or had no working hours. This is contrary to the other two time periods when many TVET graduates worked 40–55 hours per week.

COVID-19 Impact on Income

Self-employed graduates experienced a decline in median income from 25,000 Sri Lanka rupees (SLRs) per month before the pandemic to SLRs15,000 as of November 2020. This is a 40% decline compared to pre-COVID-19 and is by far larger than the 8.3% global income decline (ILO 2021). The monthly salary distribution for self-employed graduates showed salary declines after the pandemic.

Despite these challenges in self-employment, COVID-19 seems to have spurred entrepreneurship for some TVET graduates who lost their jobs. In particular, female entrepreneurs who had taken beautician and tailoring courses increased in 2020.

Wage employees experienced less of a decrease, with median monthly wages decreasing from LKR 34,000 to LKR 30,000 (12% decline). For wage workers, the distribution shifted toward the left but only marginally. The peak of the distribution was clearly around LKR 35,000 before COVID-19 but the peak plateaued between LKR 20,000 and LKR 35,000 during the pandemic. More than half of employed TVET graduates attributed the reduction in income as a COVID-19 impact since many of them could not go to the office between March and June 2020. At the time of November 2020

Future solutions

Moving forward, it is recommended to provide financial support for TVET instructors and students to enable access to the internet and hardware devices. Professional training for online training delivery is also needed for TVET instructors because they still use the traditional in-person curriculum and pedagogy for online teaching. TVET could also benefit greatly from the use of medium-tech solutions using online collaboration technologies. The new high- tech solutions, such as simulation and virtual laboratories could also enable practical training online.

These high-tech solutions were seldom used during the pandemic and learning outcome needs to be examined in the Sri Lanka context when high-tech solutions are introduced. Due to COVID-19, more TVET graduates may enter the labour market without sufficient practical training. Thus, employers’ reactions need to be also examined as a future area of research. Last but certainly not least, the mindset of TVET instructors needs to change and further actions need to be taken to embrace online learning opportunities to realise the “Decade of Skills Development” in 2021–2030.