Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

At the turn of the Twentieth Century, Ceylon’s struggle for independence had rippled across the length and breadth of the island with an unwavering vision to break the chains of colonial servitude. While there were many who travelled to the far corners of the island to gather support for this struggle, there was a man who believed in the power of the written word that originated from the editorials of Lake House to explain the worth of self-rule to the common people.

The late D.R. Wijewardene, founder of the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. is remembered as a man who worked among minds. Few can match the influence he had over the course of the island nation’s history. He understood that the media was inseparable from the strength of the nation and that democracy is dependent on the quality of information the people receive.

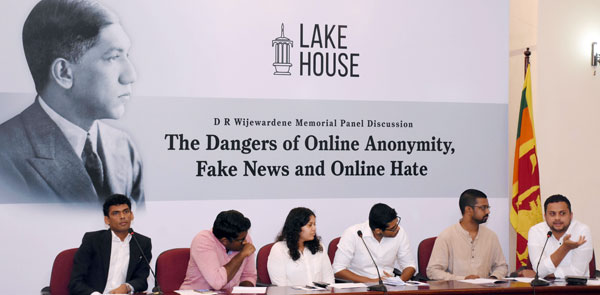

The D. R. Wijewardene memorial panel discussion was held at the Lakshman Kadiragamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies, as the nation celebrated the 131st birth anniversary of the press magnate. Organisers of the event noted that D.R. Wijewardene laid the foundation for Sri Lanka’s independence by understanding that the 20th Century would be redefined by the media. In keeping with his pioneering principles, the discussion explored the present dangers of online anonymity, fake news and online hate with contributions from the country’s leading media institutions, Lake House and Wijeya Newspapers together with online media platforms Ground Views, Yamu and Aniwa.lk.

Finding a balance in sensationalism, catchy headlines and the need to break news fast with accuracy was among the key challenges explored throughout the evening. The panelists included several editors of digital media platforms, entrepreneurs and journalists who attempted to tackle the grey areas of integrity in online journalism. The panelists included Rasika Jayakody from Lake House, Raisa Wickrematunga from Ground Views, Umair Wolid from Wijeya Newspapers, Indi Samarajiva from Yamu and Anisha Yasarathne of Aniwa.lk.

Discussing misleading news, click-bait and media bias, Rasika Jayakody attempted to differentiate fake news from bad journalism. “When we started journalism there were two views; ‘news’ and ‘not news’. News goes to the paper and not news will be left out. There was misinformation, disinformation, fabricated stories, cooked up stuff, all with elements of bad journalism. Today there is a new entity called fake news especially in the light of the US election. What differentiates fake news from bad journalism is the intent and the style of publishing,” Jayakody opined.

“In our newsrooms we try we try our best to get news right because we don’t want mistakes. Our intention is to get it right and there are various bodies and frameworks to monitor these. Fake news [ articles] do not have frameworks. They [publishers] know in very clear terms that their purpose is the clear factor. Their objective is to use fake news to earn money, more hits or to aid some campaign,” he added.

Jayakody cited examples of fake news with stories such as Donald Trump being endorsed by the Pope in the run to the US Presidential Election. He also spoke of the more recent news that US changed its VISA accreditation on Sri Lanka. According to Jayakody these stories define fake news.

“One hundred years ago D. R. Wijewardene had the required amount of capital to start a large scale publishing company. Now the manufacturing cost of news and information has gone down to zero. Everyone is a publisher at least on social media. There is a huge influx of fake news online and we can’t do anything about it. We need to single out fake news from bad journalism,” he said.

Speaking further on the distinction between fake news and news that is inaccurate Umair Wolid of Wijeya Newsapapers spoke of how private media entities confront the new financial rival that that is fake news. According to Wolid fake news dissemination happens in two ways. While some stories are published purely with financial or political intent, some are the result of poor fact checking.

“The US visa story, was picked up by Sri Lankan websites which said that Sri Lankans could travel visa free to the US. That was pure fake news. Its intent was not to pull out the fake news but it displayed a lack of fact checking. This is a common issue in any media institution. The entire news industry is so competitive because everyone wants to break their news first. There is no excuse for journalism sans fact checking. It is becoming a major issue at the moment. Paying news vs. false news are actually two dilemmas that modern journalists need to worry about,” Wolid said.

Following these remarks the panelists were then questioned if there are instances where fake news can be good or useful. In response to the question, Indi Samarajiva of Yamu, an online media presence that sparked heated debate for its content on social media recently – took a rather unusual stance on the subject. He declared that fake news is not necessarily bad as often portrayed.

“If you have a weapon, you don’t ask if the weapon is real or not, you just ask if it is effective. If media is a weapon and you need to get what you want, then why not make it fake? Fake news allows a lot of people into the media establishment. Even now you need capital to have a media organisation. With access to a web server many people can be reached,” Samarajiva said adding that alternative media outlets empowered the disenfranchised to voice their opinions.

However Raisa Wickrematunge of Groundviews countered this argument in response to the questions posed if fake news was a danger to democracy. “I think it’s interesting that you think fake news is a stone that could be thrown at the establishment. When I’ve written about the media I have often said that it’s like you’re holding an unexploded grenade. And you are not aware of the power you wield. That might be an interesting analogy. Having said that, fake news also has a negative impact.” Wickrematunge then went on to narrate a personal encounter in 2012 where she was a victim of fake news. In 2012 an article written by Wickrematunge had been picked up by another news outlet. The cooked up story had evolved into a news report alleging that she had been arrested. Wickrematunge notes that whenever her name is Googled, one of the things that appear in the results page is a false report of her arrest.

“When you don’t verify things it does have an impact on people. While for me this is an interesting anecdote, there are instances where it negatively impacted people’s lives. For instance in November there were two unarmed university students shot dead by police in Jaffna. One newspaper said that they were driving banned motorcycles, with the hope this somehow excused what happened. This was then picked up by several news organisations who reported it without fact checking. Imagine the feelings of the families of the victims when they saw this news. It is important to note that when you don’t verify things it can have a negative impact on people’s lives,” she cautioned.

The panelists went on to discuss the willingness of an editorial team to balance sensationalism and reporting the truth. Anisha Yasaratne of Aniwa.lk said that reports are mostly formulated from the point of view from individual media organisations whose abilities are often restricted.

If your goal is to be a sustainable media organisation I don’t think that you can push the envelope too far when you’re crafting your click-bait for a website. When you draft your headlines and taglines, you would be doing yourselves a disservice if you don’t represent the content of your article in the headline itself. In the Sinhala media space, if you don’t do news you’re automatically cast into the gossip sphere which is very veracious. It is also a necessity to be a little extreme these days because you’re competing with so many other publications. You have to balance this with the truth. If you don’t you’re not going to last too long,” he said.

The panelists went on to explore the restrictions and limitations media could and should draw in reporting with sensationalism and questioned as to where the lines could be drawn. While the audience could not clearly comprehend a conclusive account through the question and answer session at the end of the discussion a number of interesting queries were posed by the audience. This included the redaction of popular names and the selection of editorial content by each media organisation. However the panelists were firm in their stance that when questioning people’s identities and religion through reports of the media must be approached with caution and calls for better preparation for the reactions it may cause.

Pix by Kushan Pathiraja