Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Letters have been written for various reasons throughout history and they occupy a specific and special place in literature. While many were centred on personal, political, social and economic matters very few focused on building bridges for peace and harmony among communities and ethnic groups within and outside territorial boundaries.

economic matters very few focused on building bridges for peace and harmony among communities and ethnic groups within and outside territorial boundaries.

The 30-year war, which began in 1983, left scars of distrust and division between the Tamil and Sinhala communities that had lived in harmony together for centuries. The wounds of repression and rejection of the Tamil-speaking Northern and Eastern communities are yet to be healed.

Brutal war

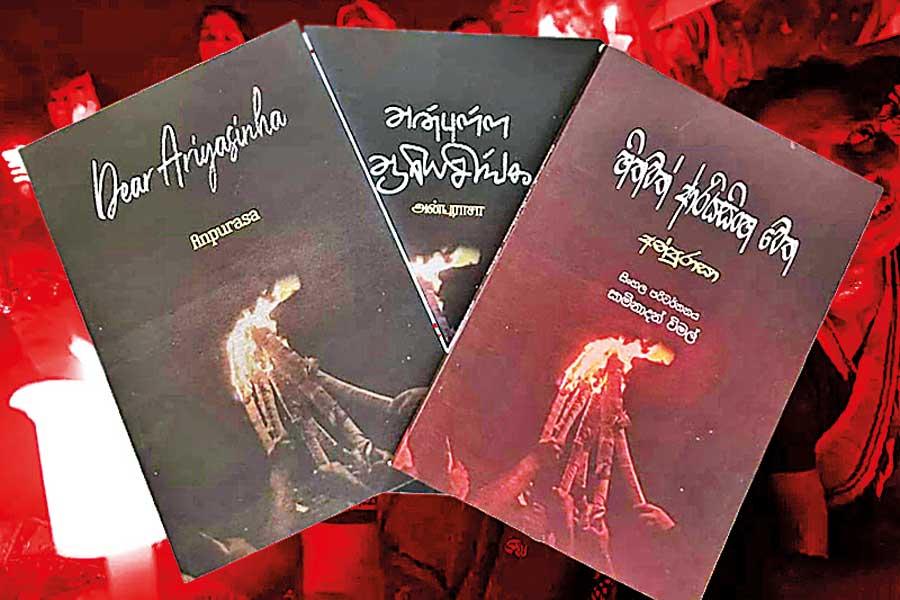

In this fictional novel, ‘Dear Ariyasinghe’, Rev. Fr. Sebamalai Ampurasa (OMI – The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate), a victim of the brutal war in the North expresses his solidarity and extends a hand of friendship to his Southern Sinhala friends through letters addressed to a Sinhala youth named Ariyasinghe who was part of the Aragalaya, a struggle launched in 2022 by the poor and the lower middle class in the South to effect a system change.

Battered and bruised by the bloody 30 year war, Ampurasa, who represents the ‘Tamil experience’, tells, Ariyasinha, who symbolically denotes the Sinhala community that he and the

|

Rev. Fr. Sebamalai Ampurasa |

Sinhala community are not alone in the economic crisis created by the self-centred decisions of the Rajapaksas. Even though most Sinhala people were against the Northern and Eastern Tamil community during the war during which the Tamils had gone through untold misery for well over three decades under the oppressive hand of the government.

Economic embargo

Throughout the text, Reverend Ampurasa flags an important issue which is clearly characterised in the following lines of the first letter: “Today you mourn over the daily blackouts, fuel scarcity, cooking gas and milk powder. You feel helpless over the rising prices of essential items. But, we survived for over three decades without any of these commodities because of the economic embargo imposed by the government on the North and the East. We have sacrificed our childhood and adult lives voicing against the violations. The rest of our lives and that of our kids have been wasted in the same way”.

Through the 30 letters “Dear Ariyasinghe” Ampurasa poses the question of where were the Sinhala people for the last thirty years while their Tamil brethren suffered much pain for just being Tamil. The Aragalaya that lasted for a short time cannot by any means be compared to the 30 years of suffering at a much greater degree that the people in the North and the East had endured.

The author refers to a period of recent Sri Lankan history that has hardly become the collective Sinhala memory or its conscience. He refers to the recent economic crisis in the country which is not new to the people in the North who have been forced to lead a meagre existence for years. What is dismaying, according to Ampurasa, is the capacity of the majority to feel the pain of others. It has been lost among larger sections of the Sinhala society because empathy has been ethnicised.

This collection of letters reminds everyone that peace is neither the absence of war nor the false assurances given to minorities that their rights will be restored and respected. However, the call to let bygones be bygones and enter a new beginning where one day all communities could sit together at the table of brotherhood is extended to the Sinhala brethren.