Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Approximately 70 to 80 cases of WhatsApp hacking have been reported to SLCERT over the past two to three months

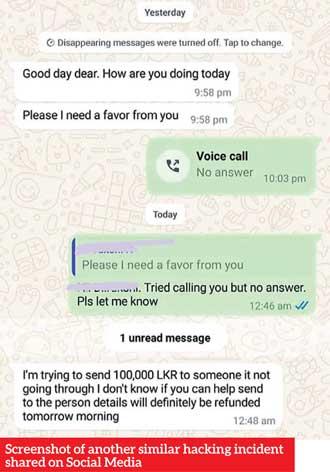

Hackers exploit the account by impersonating the victim and sending messages to their contacts, often requesting money under false pretenses. The lack of Meta support teams in Sri Lanka complicates the matter. While SLCERT can offer some technical assistance, victims must approach the Computer Crimes Division of the CID for investigations

In the recent wave of WhatsApp hackings in Sri Lanka over the past two months, journalists have emerged as the latest victims. According to informal reports, nearly 10 WhatsApp accounts belonging to Sri Lankan journalists were hacked during the recent weeks.

In the recent wave of WhatsApp hackings in Sri Lanka over the past two months, journalists have emerged as the latest victims. According to informal reports, nearly 10 WhatsApp accounts belonging to Sri Lankan journalists were hacked during the recent weeks.

Alarmingly, approximately 70 to 80 cases of WhatsApp hacking have been reported to Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Readiness Team (SLCERT) during the past two to three months. The majority of victims have reported sharing codes with callers from international numbers which had led to their accounts being hacked, while a few others have said that simply answering international calls led to the hacking. So, what exactly is happening, and why are politicians, journalists, and other WhatsApp users falling prey to these hacking schemes?

Journalist Izzadeen a recent victim

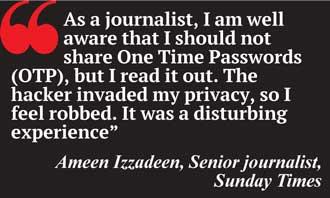

Senior journalist at the Sunday Times, Ameen Izzadeen, was one of the recent victims of WhatsApp hacking when his account was compromised on November 20.

Speaking to the Daily Mirror on Tuesday (November 26), Izzadeen recalled the incident. “I had taken painkillers and was resting while suffering from a flu when I received the call. I was still drowsy when the caller asked if I was taking part in the Zoom meeting. Since I was actually looking forward to a Zoom call related to the recent elections, I assumed the caller was referring to that meeting, so I said yes. He then immediately said that a number would pop up on my screen and asked if I could read it out so he could send the Zoom link. As a journalist, I am well aware that I should not share One Time Passwords (OTP), but in my state, I read it out,” Izzadeen recalled.

Unsure of what to do next, Izzadeen first blocked the caller on WhatsApp. However, the hacker had already accessed his contacts. Although Izzadeen tried to regain control of his account, he was informed that an OTP had already been sent to the new device (the hacker’s device).

“I was unsure what to do, so I started calling my friends, informing them about the incident and asking them to warn others. I contacted SLCERT, but they didn’t have a solution and only advised me on what to do. They recommended downloading the WhatsApp Business app from the Play Store, which would deactivate the other account. However, when I installed the app, I was informed I would need to wait seven to eight hours. I also visited my mobile network operator, but they said they couldn’t help since it was a third-party app. So I waited seven to eight hours before creating a new account on WhatsApp Business, which finally disconnected the compromised account,” he explained.

“I was unsure what to do, so I started calling my friends, informing them about the incident and asking them to warn others. I contacted SLCERT, but they didn’t have a solution and only advised me on what to do. They recommended downloading the WhatsApp Business app from the Play Store, which would deactivate the other account. However, when I installed the app, I was informed I would need to wait seven to eight hours. I also visited my mobile network operator, but they said they couldn’t help since it was a third-party app. So I waited seven to eight hours before creating a new account on WhatsApp Business, which finally disconnected the compromised account,” he explained.

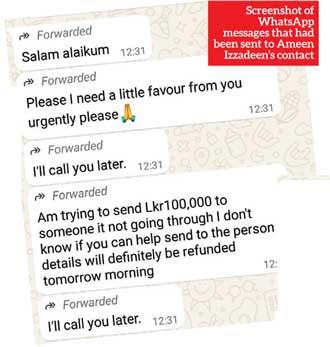

Izzadeen added that some of his contacts, who had received messages from the hacker asking them to deposit funds to a local bank account, had taken proactive measures by contacting the relevant bank manager and providing the account number.

Izzadeen also lodged a written complaint with the Computer Crimes Division of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) via email. While he was informed that an officer would be in touch soon, no one has contacted him so far.

“The hacker invaded my privacy, so I feel robbed. It was a disturbing experience,” Izzadeen shared.

Ordeal faced by MP Mujibur

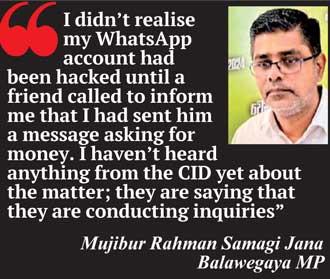

The WhatsApp hacking scheme gained widespread attention when Samagi Jana Balawegaya MP Mujibur Rahman filed a complaint with the Computer Crimes Division of the CID on  October 28 after his WhatsApp account was hacked.

October 28 after his WhatsApp account was hacked.

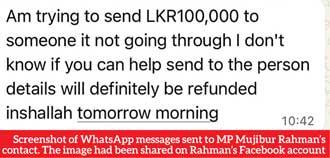

Speaking to the Daily Mirror on Monday (November 25), Rahman recounted his experience. He explained that he had received a WhatsApp call from an unknown UK number. The caller claimed that a Zoom meeting had been organised to discuss the situation in Palestine. As it was the General Election campaign period, Rahman informed the caller that he would be unavailable. However, the caller—who Rahman noted spoke with an Arabian accent—had insisted that Rahman participate in the said Zoom meeting. The caller had then told Rahman that a code for the Zoom meeting had been sent to his WhatsApp account. Unknowingly, Rahman repeated the code to the caller.

“I didn’t realise my WhatsApp account had been hacked until a friend called to inform me that I had sent him a message asking for money,” Rahman shared. The hackers, impersonating Rahman, requested money from his contacts, resulting in around five to six individuals transferring a total of Rs. 600,000 to bank accounts provided by the hackers. These accounts were linked to areas such as Buttala and Nawalapitiya. “I haven’t heard anything from the CID yet about the matter; they are saying that they are conducting inquiries,” Rahman said.

“It took nearly one and a half days to retrieve my account,” Rahman added. He mentioned that he had sent an email to Meta, the parent company of WhatsApp, to report the hacking, and the CID had also contacted Meta regarding the incident.

“It took nearly one and a half days to retrieve my account,” Rahman added. He mentioned that he had sent an email to Meta, the parent company of WhatsApp, to report the hacking, and the CID had also contacted Meta regarding the incident.

Rahman further noted that the caller seemed aware of his status as a parliamentarian.

The experience of Amal Bandaranayaka

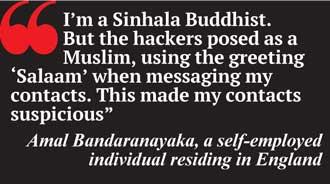

Before MP Mujibur Rahman’s account was hacked, there were other reports of WhatsApp accounts being compromised, with callers claiming to invite people to election meetings via Zoom. Amal Bandaranayaka, a self-employed individual residing in the UK, shared his experience with the Daily Mirror.

Bandaranayaka had been a member of a WhatsApp group named ‘NPP UK.’ About two or three months ago, he received a WhatsApp call from a UK number with a profile picture displaying the logo of the ‘NPP UK’ group. Being actively involved in political activities, he did not hesitate to answer the call. The caller informed him about a National People’s Power  (NPP) meeting and asked if he could join on a specific date. When Bandaranayaka agreed, the caller had mentioned that a Zoom code had been sent to his WhatsApp account to facilitate access to the meeting. Upon reading the code aloud, Bandaranayaka suddenly became suspicious and requested the caller to resend the code. However, it was already too late. The caller had clearly heard the code and realised that Bandaranayaka had grown suspicious. Almost immediately, Bandaranayaka lost access to his WhatsApp account.

(NPP) meeting and asked if he could join on a specific date. When Bandaranayaka agreed, the caller had mentioned that a Zoom code had been sent to his WhatsApp account to facilitate access to the meeting. Upon reading the code aloud, Bandaranayaka suddenly became suspicious and requested the caller to resend the code. However, it was already too late. The caller had clearly heard the code and realised that Bandaranayaka had grown suspicious. Almost immediately, Bandaranayaka lost access to his WhatsApp account.

Being in the UK, Bandaranayaka contacted the hacker’s number directly. The person who answered informed him that his own WhatsApp account had also been hacked a week prior and confirmed that the callers were hackers. He had also revealed that the hackers would try to request money from Bandaranayaka’s contacts. Despite several attempts to log back into his account, Bandaranayaka was locked out for 11 hours. After this period, he had requested the verification code via a phone call and successfully retrieved his account. However, while he was logged out, the hackers had sent multiple messages to his contacts requesting money.

“I’m a Sinhala Buddhist,” Bandaranayaka noted. “But the hackers posed as a Muslim, using the greeting ‘Salaam’ when messaging my contacts. This made my contacts suspicious,” said Bandaranayake.

Bandaranayaka also mentioned that he had been a member of a WhatsApp group named ‘South London Cricket Club (SLCC)’, and one of the members of that group had received a call from a UK number whose profile picture displayed the SLCC logo.

According to Bandaranayaka, the hackers requested £900 from his contacts in the UK and Rs. 40,000 from those in Sri Lanka.

“When I reflect on this incident, I feel unsettled because the call was clearly suspicious. But, at the same time, I was occupied with work when I received the call, which is why I didn’t think much about it,” he remarked.

Modus Operandi

To understand the situation better, the Daily Mirror reached out to Charuka Damunupola, Lead Information Security Engineer at the Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Readiness Team (SLCERT).

To understand the situation better, the Daily Mirror reached out to Charuka Damunupola, Lead Information Security Engineer at the Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Readiness Team (SLCERT).

Damunupola explained that victims typically receive a message from someone in their WhatsApp contacts or a call from an international number inviting them to join a Zoom meeting. The topic of the meeting often relates to the victim’s interests, such as elections or religious discussions. Shortly after, the victim receives a verification code, which the hacker claims is required to access the Zoom call.

This code, however, is the victim’s WhatsApp verification code. Sharing it allows the hacker to re-register the victim’s WhatsApp account on their device, effectively locking the victim out of their account.

“The danger is that the hacker will enable two-step verification on their end,” Damunupola explained. “When the victim tries to log back in and requests the verification code, it will be sent to the hacker’s email or device. Resetting this two-step verification typically requires a cooling-off period of 48 to 72 hours, as part of WhatsApp’s spam detection mechanism,” said Damunupola.

During this time, hackers exploit the account by impersonating the victim and sending messages to their contacts, often requesting money under false pretenses. “Since the number belongs to someone they know, contacts are more likely to comply, whether by sending money or sharing another code,” Damunupola added. “The main issue here is sharing the OTP, or WhatsApp verification code, with unauthorized parties,” he said.

Damunupola advised victims to immediately alert their contacts via a call or text message if their WhatsApp account is hacked. They should warn them not to engage with messages from the compromised account.

Users warned to stay vigilant

“It’s highly unlikely for your WhatsApp to be hacked just by answering a phone call unless you disclose an OTP or verification code that appears on your screen,” clarified Damunupola. He warned users to stay vigilant, as scammers might refer to the code using different terms such as “reference number,” “admission number,” or similar phrases to deceive victims into sharing it.

However, when this journalist queried about reports of accounts being hacked just by answering a call from an unknown international number, Damunupola explained that on rare instances, returning a hacker’s call can lead to one’s WhatsApp account being hacked.

“In rare cases, people could have their accounts hacked after returning a call from an international number. If you receive international calls or see missed calls from international numbers, don’t call them back, because it can go to a different channel which will activate your call forwarding option; once it’s activated, your calls will be forwarded to the hacker’s device and through that he can set up the WhatsApp account by requesting a phone call. However, this isn’t the most popular way of hacking WhatsApp accounts,” he elaborated, adding that enabling two-step verification on one’s WhatsApp account would protect one from such hacking attempts.

Why are journalists targeted?

When a person’s WhatsApp account is hacked, their contacts — often in the same profession or part of related groups — become the next targets. “For example,” Damunupola explained, “if a teacher’s account is hacked, it’s likely that several other teachers’ accounts who are in the contact list or in the same groups will be hacked too.”

Do hackers impersonate the individual?

Do hackers impersonate the individual?

Damunupola explained that once a person’s account is hacked, the hackers often study their contact list and group memberships to gather information about the individual. “In one case, a priest or pastor’s account was hacked. The hacker reviewed the contact list and group chats to deduce that the account belonged to someone involved with the church. Then, the hacker crafted a convincing story, claiming to be organising a donation or charity event for the church, which led many in the contact list to believe it was genuine,” he said.

He further noted that the initial incidents reported about 2–3 months ago primarily targeted members of the Muslim community. “The story involved an online prayer discussion, which is why many Muslims were victimised in the early stages,” he said.

Since then, SLCERT has recorded 70–80 cases of WhatsApp hacking according to Damunupola. “In most instances, the hackers requested victims to transfer sums ranging from Rs. 50,000 to Rs. 100,000. We’ve encountered numerous cases where individuals sent the money without thinking twice,” he added.

Are locals involved in this scam?

The involvement of local bank accounts in the hacking scheme raises questions whether locals are also involved in this scam. However, Damunupola stated whether Sri Lankans are involved remains unclear.

“The police has to conduct investigations to find that out. Also, to get the complete picture of the situation, they have to obtain court orders on these bank accounts to which the money gets deposited. So there are several factors and it will take some time to determine this,” Damunupola explained.

How would the authorities curb the issue?

Damunupola explained that the lack of Meta support teams in Sri Lanka complicates the matter. While SLCERT can offer some technical assistance, victims must approach the Computer Crimes Division of the CID for investigations.

“There are significant technical challenges. No agency has access to the data of the account holders involved in these activities. We also lack login details like subscriber information, which can only be obtained by coordinating with Meta. They usually won’t disclose such information without a court order, and even then, investigating IP (Internet Protocol) details requires a thorough investigation. Hackers or scammers often don’t deposit money directly into a single account,” Damunupola explained.

He also pointed out that in many cases, the accounts being used could belong to deceased individuals or those with drug dependencies, who are unaware of the situation. Additionally, some of these accounts may be managed by university students who mistakenly believe they are doing an online job. As a result, investigations are complex and take time, Damunupola stressed.

What to do if your account is hacked

1. If your account is hacked, try uninstalling and reinstalling the app.

2. Then try to register your number again. Typically, you’ll receive an SMS with a verification code. However, if the hacker has enabled two-step verification, the code may be sent to their email. In this case, choose the option to receive the code via SMS to regain access.

3. If option 1 doesn’t work, uninstall the app and install the WhatsApp Business app. Then, attempt to register your number on the new app. If successful, your previous account will be deactivated.

4. You can also contact WhatsApp support via email to report the hack, though their response may be slow.

5. If you or any of your contacts have transferred funds to the hacker’s account, file a complaint with the CID. However, recovering the funds is often unlikely.

How to protect yourself from hackers

● Avoid answering calls from unfamiliar international numbers, although the profile picture may seem familiar to you.

● If you see any missed calls from unfamiliar international numbers do not call them back. There is a chance that your WhatsApp account could be blocked when you return a hacker’s call.

● Never share any codes you receive with others. Hackers may ask you to provide what they claim are reference or admission numbers, or something similar. Even if the request comes from a close contact, do not disclose such information.

● Avoid sharing sensitive personal details, such as bank account numbers or your National Identity Card number.

● Take advantage of the security features offered by WhatsApp, including enabling two-step verification to add an extra layer of protection.

● Be cautious about what is posted in group chats. Avoid clicking on any links that claim to lead to calls or offer prizes.

● Enhance your WhatsApp privacy settings, such as allowing only your contacts to add you to groups. However, this may not be effective if one of your contacts’ accounts has already been compromised.