Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

The issue of female labour force participation in Sri Lanka has remained a subject of discussion for several decades, yet tangible progress in improving it has been elusive. As the country grapples with its most severe economic crisis since gaining independence, it is important to take a hard look at our labour force to maximize its potential in overcoming the economic crisis.

The issue of female labour force participation in Sri Lanka has remained a subject of discussion for several decades, yet tangible progress in improving it has been elusive. As the country grapples with its most severe economic crisis since gaining independence, it is important to take a hard look at our labour force to maximize its potential in overcoming the economic crisis.

Sri Lanka is approaching its last stages of its demographic dividend characterized by a significant proportion of its population falling within the working age bracket (typically aged 15-64) in relation to the dependent age categories, the aged and the children.[https://srilanka.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/IPS-and-UNFPA-Report-May-2014.pdf] According to the Asian Development Bank, Sri Lanka’s working-age population is expected to reach its peak around 2027.[ https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/557446/aging-population-sri-lanka.pdf] This presents a unique opportunity for us to strengthen our economic prospects by using the right socioeconomic policy mix, similar to how the Tiger economies like Singapore, Hong Kong etc. have harnessed their demographic dividends to advance their economic growth.

Importantly, a substantial portion of this working-age population comprises highly educated and women who are living longer. Hence necessary interventions must be made to harness their economic potential.

Current status of the labour market

According to the 2021 Labour Force Survey, Sri Lanka’s total labour force The Department of Census and Statistics (2021) defines the labour force as individuals aged 15 years and above who are economically active, encompassing both the employed and the unemployed during the reference period, comprises 8.5 million individuals, with 65% of them being male. The overall labour force participation rate (LFPR) in Sri Lanka hovers around 50%, revealing a significant gender gap that has persisted since the early 2000s. As of 2021, the male labour force participation rate in the country stands at 71%, whereas the female labour force participation rate is considerably lower at 31.8%. This enduringly low female labour force participation rate, spanning almost a decade, necessitates increased attention and intervention from the government. It represents an untapped potential within our economy that demands harnessing for the nation’s benefit.

When examining the female labour force participation, it becomes evident that a significant proportion of females are employed in the estate sector, constituting 42.6% of the female workforce. In the year 2021, a substantial majority of the economically inactive population [As defined by the Labour Force Survey (LFS), economically inactive individuals encompass all persons who did not engage in employment and were neither available nor actively seeking work during the reference period] were females, accounting for approximately 73.3%. Interestingly, among these economically inactive women, 59.4% cited engagement in household work as their primary reason for not participating in the labour force. This sheds light on household responsibilities as the main contributing factor, preventing women from entering the workforce.

Education status of the labour market

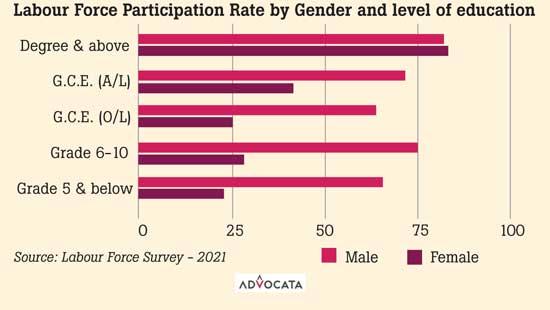

Sri Lankan women tend to achieve higher levels of education compared to men.[ https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-colombo/documents/publication/wcms_551675.pdf] However, this educational advantage hasn’t translated into higher levels of participation in the labour force. To illustrate this relationship between labour force participation and education, the chart below provides a clear visual representation of the situation.

This diagram highlights two important points. Firstly, it reveals that a significant majority of women who participate in the labour force (83.2%) possess degrees or higher levels of education. This suggests that women are more likely to apply for jobs that align with their skill set and education level.

Secondly, it underscores a distinct contrast when it comes to men. Even if men have an education level of grade 5 or below, a substantial portion (65.7%) still actively contribute to the economy. This disparity suggests that women with lower levels of education face greater challenges or barriers when it comes to workforce participation compared to their male counterparts.

This statistic also serves as a clear illustration of the traditional societal norm of men being the breadwinner, which leads to men having higher labour force participation rates, irrespective of their educational levels. On the other hand, women, despite their advanced educational qualifications, may encounter societal pressures or constraints that discourage them from seeking or maintaining employment. Unemployment remains a significant challenge in Sri Lanka, with the highest rates observed among women holding education levels at Advanced Level and above. This represents a substantial untapped pool of potential in the Sri Lankan labour market.

Reasons for low Female Labour Force Participation despite having a high education level

The low female labour force participation rate in Sri Lanka can be attributed to a range of socioeconomic factors.

A primary factor that discourages women from actively contributing to the economy is the significant burden of care responsibilities they bear. This care work encompasses a broad range of household tasks, from cooking and cleaning to childcare and caring for the elderly. According to the 2017 Time Use Survey, women spent nearly four hours more per day on unpaid care work and domestic services compared to men. For many decades, there has been a prevailing societal stereotype that women are primarily responsible for managing households, while men are expected to be the breadwinners outside the household. This division of labour is a key reason why women with the qualifications and capabilities to pursue employment opportunities often choose to stay at home, while men even with lower levels of education enter the labour market.

Another significant factor is the existing legal barriers in Sri Lanka. The two prominent legal constraints are restrictions on night-time work and the absence of recognition for part-time employment. While these legal provisions may have initially aimed to protect women, they inadvertently discriminate by limiting their employment opportunities and earning potential. For example, IT/BPM sector employment is affected by the 1954 Act [Shop and Office Employees (Regulation of Employment and Remuneration) Act No. 19 of 1954] which only permits women over the age of 18, to work till 8 p.m. The current statutory regimes governing employee rights fail to recognize part-time work. This oversight leads to a reluctance by employers to hire part-time workers as they are entitled to the same benefits as full-time workers.

Moreover, the absence of adequate social infrastructure, such as quality childcare centres and comprehensive parental leave policies, contributes significantly to the low female labour force participation rate. Presently, in Sri Lanka, approximately 80% of childcare centres are privately operated. This situation creates a barrier to accessing quality and affordable childcare facilities, making it financially challenging for skilled women to participate in the labour force, as many opt to stay at home to care for their children due to these constraints.

As highlighted in an ILO report the presence of skill mismatch [“Skill mismatch” refers to the disparity between the skills available in the labour market and the skills that are in demand] in Sri Lanka’s labour market since the early 1970s contributes as another reason. [https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-colombo/documents/publication/wcms_359346.pdf] This skill mismatch exists because the country’s education system does not adequately prepare graduates with the skills required by the job market. There is a notable disconnect between the courses offered by universities and the competencies needed by the private sector.

This mismatch also contributes as a reason for the high levels of youth unemployment and the prevalent issue of arts degree holders struggling to find employment. A staggering 43.9% of unemployed graduates possess degrees in the arts. [http://www.statistics.gov.lk/LabourForce/StaticalInformation/AnnualReports/2021] Notably, the majority of arts degree holders are women. This situation underscores a disconnect between the demand and supply within the labour market. It suggests that the current education system is not adequately preparing graduates with the skills and qualifications needed to meet the demands of available job opportunities.

Addressing these barriers is vital to improving the labour force participation rates, especially among women.

Policy Recommendations

Recognise part-time work under the existing statutes provide needed benefits such as annual leave and remove provisions which restrict women from working at night.

Utilize local government mandates via by-laws to enact local legislation to set up standardized and regularized daycare centres while encouraging Public-Private partnerships in providing care for children by utilizing existing infrastructure.

Introduce more courses and degrees which are required by the private sector. This should be specially done by focusing on arts graduates.

The effectiveness of the aforementioned policies would be limited if we do not address the need for a shift in people’s mindsets. While Sri Lanka has made progress in challenging gender stereotypes there is still much work to be done. Initiating change, particularly within the education system, presents a promising starting point. The prevailing patriarchal system can be challenged and dismantled through education, which has the power to instil in both men and women the belief that predefined gender roles are unnecessary.

Thathsarani Siriwardana is a Research Assistant at Advocata Institute. She can be contacted via [email protected]. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated

with the institute.