Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

When I heard Gordon de Silva was not a little distraught and unwell, I remembered the first time I met him, somewhere in 2014. It was at the Rupavahini Corporation and he was, if I remember rightly, nearing his retirement. He had a story to tell and that story, when I reflected on it later on, seemed to deserve more than the usual 1,500-word sketch. Back then, word limits were considered “secondary” to the content of the story, so I went on writing, sketching the man’s life and work. I can’t say that I was happy with the final draft, but then those who write on people like Mr. Gordon can never be happy with what they write.

When I heard Gordon de Silva was not a little distraught and unwell, I remembered the first time I met him, somewhere in 2014. It was at the Rupavahini Corporation and he was, if I remember rightly, nearing his retirement. He had a story to tell and that story, when I reflected on it later on, seemed to deserve more than the usual 1,500-word sketch. Back then, word limits were considered “secondary” to the content of the story, so I went on writing, sketching the man’s life and work. I can’t say that I was happy with the final draft, but then those who write on people like Mr. Gordon can never be happy with what they write.

The truth is that the man did something. Something which would have taken decades for someone half his age and workload to accomplish. Ostensibly, he built a museum. A film museum. But museums have archivists, curators and guides, and I am not sure whether I can describe Gordon under any of those labels.

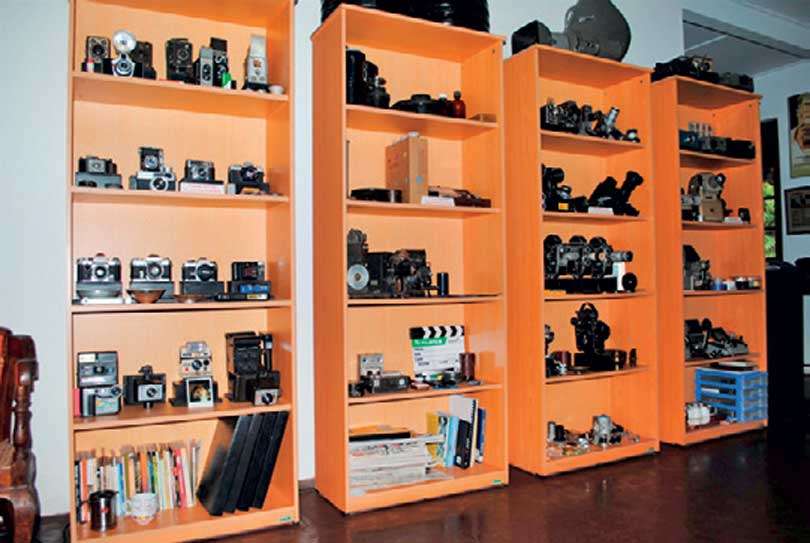

Ananda Coomaraswamy in his influential essay “Why exhibit works of art” asks us two pertinent questions: what is an art museum, and is it the only way in which we can care for works of art? Coomaraswamy’s definition of art museums would seem to fit the bill when it comes to Gordon’s institution, and on that basis it would also seem to be the best way to preserve certain objets d’art. But then the objets Coomaraswamy wrote about were cultural artefacts like paintings, sculptures and masks. He would have shuddered, given his antipathy to manufactured goods, at what Gordon had chosen to “care for”: cameras, moviolas and television sets.

As the first industrial art after photography, the cinema has always faced a paradox between the immediacy of its impact and its tendency to decompose. Pauline Kael was spot on when she claimed that “movies... fit the way we feel.” They are not cerebral and they run on a gamut of emotions. For me, though, the most potent emotion that movies inspire in us is poignancy at their decay. To be sure, digitalisation has made it possible for us to preserve the past. But in Sri Lanka, where the State has never really stepped in to protect the industry, the role of preserving it has been left to private individuals. Some do a good job, others don’t.

Mr. Gordon has done a good job, at least according to what every other person who knows him has told me. That’s why I think it’s time we revisited his story.

He was born in 1964 in Colombo. His father, Sanath de Silva, was manager of a printing press which he would, as a boy, explore. “I was always in my father’s world” was how he put it to me when I interviewed him. That world, of newspapers, tabloids and magazines, opened him to the world of films. Before he decided to do something for the industry, however, he got hooked on to another passion: constructing things. “I loved to play with toys at that age. My father made me build my own toys. All he would do was to buy the basic material for them.”

As the first industrial art after photography, the cinema has always faced a paradox between the immediacy of its impact and its tendency to decompose

Educated at Mahanama College, where he developed a flair for “building things,” he had to choose between the two paths that his parents had wanted him to follow. “My mother asked me to take to carpentry. Back then jobs like that were not looked down on. My father, on the other hand, dabbled in photography, and he passed his passion to me. Mind you, I was almost always coming across camera equipment.” Compounding this were the people that he encountered, including Wilson Hegoda, “who would later found the National Photographic Art Society.”

In the end, predictably, the mother lost. He decided to become a photographer.

So how did he move to the cinema? “Well, we went to the theatre. My father would take us to see English films once every two weeks or so. I don’t remember the plot of every film I watched, but I do remember that they were big budget epics like Ben-Hur and Cleopatra and that they remained in my mind long after I first saw them. On the other hand, my mother loved Sinhala films, and made sure we saw them too. You can say that we lived in a bilingual celluloid world. Having seen every movie, I decided, at the age of 11, to make my own slide projector. It took five years for me to build one from some matchboxes, but I did it.”

By this time he was a teenager and a precocious one at that. It hence didn’t take long for him to obsess over something else: “I watched Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs one day and I remember thinking, ‘Why not make an animated flick?’ ” The problem was that he would have to build a camera, since animated movies are clean different from live action ones. That meant that he would have to get in touch with a big shot in the field. The man Gordon turned to was in that sense a prominent figure: Givantha Arthasad, who had already made Dutugemunu.

Gordon met Givantha in 1982, right after Rupavahini was established and he had resolved to join what was then a promising industry. Givantha’s advice, after seeing him build “a device” was simple: go into television, study and then become an artist. Heeding it, he joined what became his lifelong employer in March 1983 “as a Graphic Animation Letter Artist.” The designation became a blessing when he got the chance to enter the Sri Lanka Television Training Institute (SLTII) and, through an ardent “television couple” he met there (Rainer and Nilly Welzel), got scholarships to study various related subjects, such as 3D animation in Malaysia, Canada and India. This was important, since it was in India, at the Visvasvaraya Museum in Bangalore, that he first got the idea of preserving the past.

Of course, by that time “I was already an obsessive collector. But I was a very, very undisciplined collector. I didn’t have order or method. I was also not that interested in exhibiting what I collected to the world outside.” In that sense the Bangalore Museum opened his eyes: “It had everything a film buff could hope to see and handle. I could see that the curators were meticulous about categorising the items.” His next visit, to the Martin Wickramasinghe Folk Museum in Koggala, opened his eyes more, and led him to ask himself a pertinent question: “We archive artefacts from our folk culture. So why not archive our film industry?” With this in mind, “I began collecting more and more, but with the resolve to itemise everything I got.”

The end of the voyage here was, I am inclined to say, 2009, when “I finally got to vindicate myself and started an archive.” While it was his initiative, he admits that he was spurred on to expand his “library” after a student “told me that it was a pity no one was taking the time to turn our cinema into a museum.” So on a quiet, uneventful day in November (his birthday), with the blessings of everyone, and with Sumitra Peries as Chief Guest, he opened the Museum Cinemaya in his hometown in Kottawa. The response, he remembered, was “encouraging.” That, I believe, has to do with how careful he was and is in categorising his exhibits.

Gordon told me that his museum reflects practically every stage the cinema had to go through. “Films didn’t fall from the sky. The camera was the precursor. I hence added photography to my collection. Then came silent movies. That was followed by talkies. So I began a radio collection. To promote talkies, a printing industry was begun. That was why I added a print section. Films were later uprooted by television. I devoted a section in my museum for that also.”

That world, of newspapers, tabloids and magazines, opened him to the world of films. Before he decided to do something for the industry, however, he got hooked on to another passion: constructing things

So what should a good archive contain? “Nowadays, to give you one example, we use computers as editors. There’s no need for moviolas. But the question we have to ask here is what happens to them? Do we allow them to rot, or do we preserve them? I’ve been grappling with that question for a long, long time, and I think that we should opt for preservation.” In other words, it’s not exhibiting for the sake of exhibition; there was and should be a higher purpose in the act of preserving.

The last time I wrote on Gordon, I ended with these words: “The Museum Cinemaya is in Kottawa. That’s where its founder lives. It hasn’t been completely digitised yet, and it won’t be until he manages to get every nugget of information verified. Not easy, you must admit. It’s almost always a nightmare for the archivist. But then Gordon de Silva loves what he does.” 10 years later, I am not sure whether we have progressed from that day in 2014 when I talked with him, but I am sure that we need to do more. Otherwise, we as a nation, and a people, are doomed to forget.

You can contact Gordon de Silva at 0714064647 or at [email protected]